President of the Rule of Law Institute, Robin Speed, writes about the powers of the Parliament, judicial power and the role of the High Court in making decisions about the fundamentals of criminal justice.

We are about to witness an unprecedented clash between the High Court and Parliament.

Parliament has reversed two recent High Court decisions and has thereby fundamentally changed the criminal justice system.

Never before has such a clash occurred.

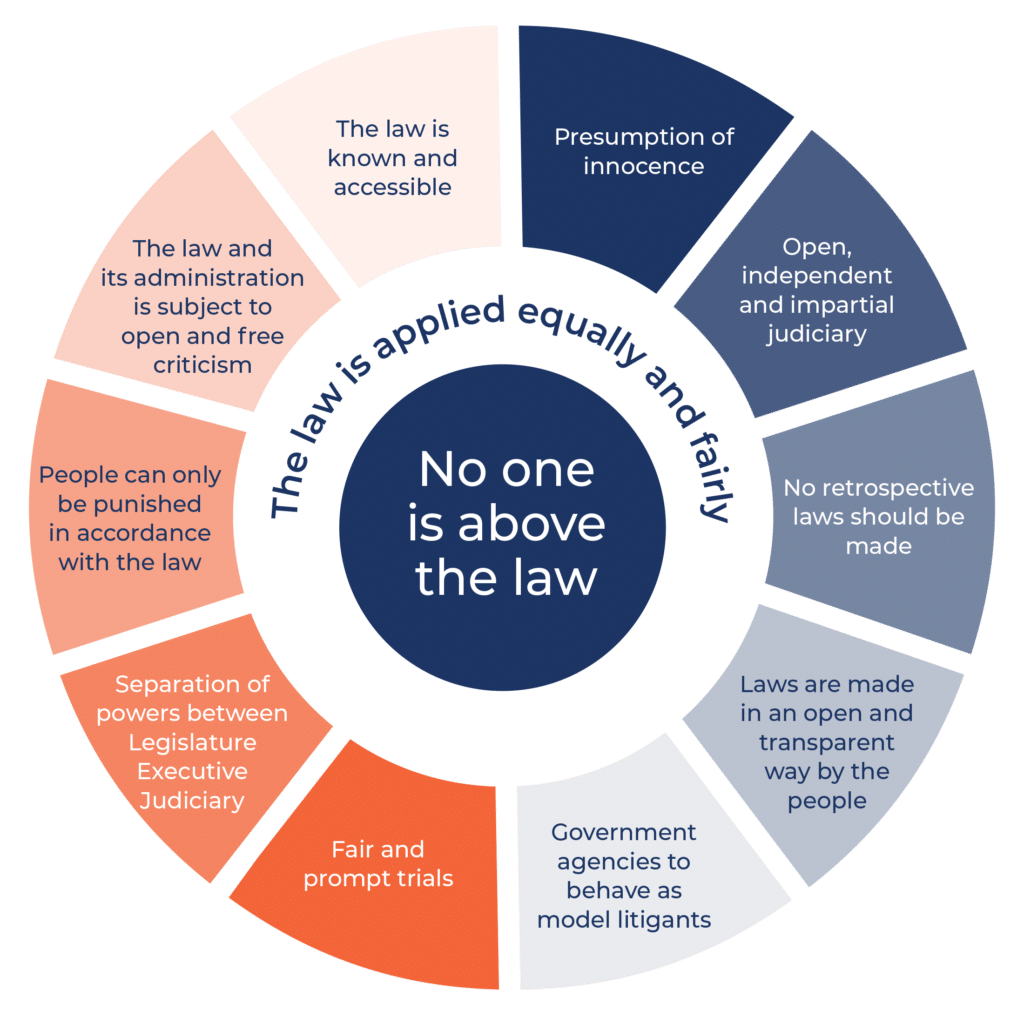

The High Court decided in the first of those cases, X7 case [2013] HCA 29 and in the second, Lee’s case [2014] HCA 20, that it was a fundamental principle of common law that it was for the prosecution to prove the guilt of a person. An accused should not be compulsorily examined after being charged, nor the prosecutor provided with transcripts of any compulsory examination.

Each of those decisions represents the considered and independent views of the highest court in the land. Each decision represents the end of a lengthy appeal process, where the matter has been debated, discussed and views formed by some of the most formidable minds in the country.

But all of this has been set aside by Parliament without any evidence that the Executive or those members of Parliament who passed the relevant Act had considered, let alone understood, the views of the High Court. Parliament has amended s24A and s25A of the Australian Crime Commission Act 2002 by the Enforcement Legislation Amendment (Powers) Act 2015, which effect from July of this year. This permits examinations of an accused after he or she has been charged, even when the questions directly relate to the subject matter of the charges and removes the Commissioner’s obligation to suppress the transcripts of compulsory interrogations.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum the amendments were based on the “principle of legality”. But this principle is no more than a rule of statutory construction that requires a clear statutory intent to abrogate or restrict a fundamental freedom or principle. It cannot be the basis of the amendments, only its effect. Rather, it is an attempt to clothe the amendments with some form of legitimacy. At best, it shows a complete lack of understanding of what was said by the High Court and at worst, an attempt to mislead Parliament. One might have expected more of an Explanatory Memorandum.

In making the amendments, Parliament is proclaiming its omniscience, its absolute power. It has become the modern day equivalent of King John, the subject of the Magna Carta. As Professor Krygier has said, the primary enemy of the rule of law is arbitrary power, because it threatens the freedom, dignity and security of the lives of those subject to it. There is the need to temper power, moderate its exercise so that it cannot be exercised at the will and caprice of power holders and so that they are required to take into account the views, interests, defences and explanations of those their power might harm.

But Parliament is not omniscient and does not have absolute power. It is a child of the Constitution and not its master.

Chapter III of the Constitution invests the judicial power of the Commonwealth in the High Court. Parliament is given no power to infringe on that judicial power. It is a short step from the constitutional requirement that judicial power can only be vested in the courts identified in s71, to the conclusion that Chapter III confers judicial power on the High Court and this entails the exclusive power to protect its content.

In the two decisions the High Court has gone to extraordinary lengths to explain the accusatorial nature of the criminal justice system and the fundamental importance of the prosecution having to prove the case; the presumption of innocence.

In the writer’s opinion Chapter III implies that any fundamental alteration to the process of criminal justice is a matter for the High Court and not Parliament. The judicial power conferred on the High Court is exclusive and necessarily involves the High Court being the guardian of the process of criminal justice. If it were otherwise, the High Court would be expected to stand by and be a witness to oppressive trials: unjust trials. That would be inconsistent with conferring of judicial power: it would leave it bereft of any substance. Nor is it simply a matter of leaving it to the discretion of the trial judge to exclude evidence. An important principle is involved. It is not a matter for each trial judge to apply in his or her own discretion.

To make this implication would require the High Court to be brave and take a bold step. But such a step is required in these extraordinary and difficult times when Parliament is not respecting the proper process of criminal justice and seeking to justify every statutory incursion on our fundamental freedoms behind the cry of protecting us from harm.

We need the High Court to stand up and protect us from greater harm – the undermining of our fundamental freedoms.

Further reading of note

Hon Chief Justice Robert French AC, ‘Statutory Interpretation and Rationality in Administrative Law‘, Australian Institute of Administrative Law National Administrative Law Lecture, 23/07/2015.

Robin Speed is the President and founder of the Rule of Law Institute of Australia, and co-founder of the law firm Speed and Stracey. He has written previously on the X7 case, and is passionate about protecting the rule of law in Australia.