It is over 60 years since the High Court’s decision in R v Kirby; Ex parte Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1956) 94 CLR 254.

This decision, handed down on 2 March 1956, was an important statement of the doctrine of the separation of powers in Australia.

This article will review the facts of the case, and trace the Court’s approach to dealing with the separation of powers in Australia, and the particular position of the federal judiciary.

The facts of the case

The Boilermakers’ case was all about the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration. This Court was in charge of preventing and settling industrial disputes that extended beyond the borders of one state. To that end, it was granted the power to determine the terms and conditions of industrial awards, and also to enforce compliance with those awards.

The Boilermakers’ case arose out such an industrial dispute.

The Boilermakers’ Society of Australia and the Metal Trades Employers’ Association had been parties to an arbitration process in the Arbitration Court, which set the employment terms and conditions for boilermakers around Australia. Subsequently, the Association alleged that the Society had breached those terms and conditions, and applied for an injunction-type order from the Arbitration Court, ordering that the Society comply. Such an order was granted, but the Society was alleged to have continued to breach the terms and conditions. Accordingly, the Arbitration Court found the Society guilty of contempt, and fined it.

The Boilermakers’ case was about the Society challenging the Arbitration Court’s power to make such a finding of contempt. The ‘Kirby’ referred to in the case’s full title is Sir Richard Kirby AC, who was one of the three judges that made up the Arbitration Court that found the Society guilty of contempt.

The key issue in the case was the distinction between judicial and non-judicial bodies and powers.

Was the Arbitration Court a non-judicial body, because of its arbitral focus? If so, could it be granted judicial powers by the Commonwealth Parliament, like the power to issue injunctions, or the power to find people guilty of contempt? Or did this breach the separation of powers?

Judicial and arbitral power

The High Court was careful to distinguish between the arbitral functions and the judicial functions of the Arbitration Court. The majority (made up of Chief Justice Dixon, and Justices McTiernan, Fullagar, and Kitto) cited a previous High Court case, Alexander’s case, where the Court had held that:

[Arbitral powers are] essentially different from the judicial power. Both of them rest for their ultimate validity and efficacy on the legislative power. Both presuppose a dispute, and a hearing or investigation, and a decision.

But the essential difference is that that judicial power is concerned with the ascertainment, declaration, and enforcement of the rights and responsibilities of the parties as they exist, or are deemed to exist, at the moment the proceedings are instituted; whereas the function of arbitral power in relation to industrial disputes is to ascertain and declare, but not enforce, what, in the opinion of the arbitrator, ought to be the respective rights and liabilities of the parties in relation to each other.

The High Court then considered whether the Arbitration Court’s main purpose was the exercise of its arbitral functions, or its judicial functions. The governing legislation of the Arbitration Court had changed significantly over the previous few decades, as a result of prior High Court challenges. These changes had periodically removed, and then restored, judicial powers – like the injunction and contempt powers – to the Arbitration Court. The majority considered this history, and decided that:

Plainly the Arbitration Court remained a tribunal established and equipped primarily and predominantly for the work of industrial conciliation and arbitration.

Thus, said the majority, it was not a judicial body. So did the Constitution permit a non-judicial body to exercise judicial power?

The separation of powers

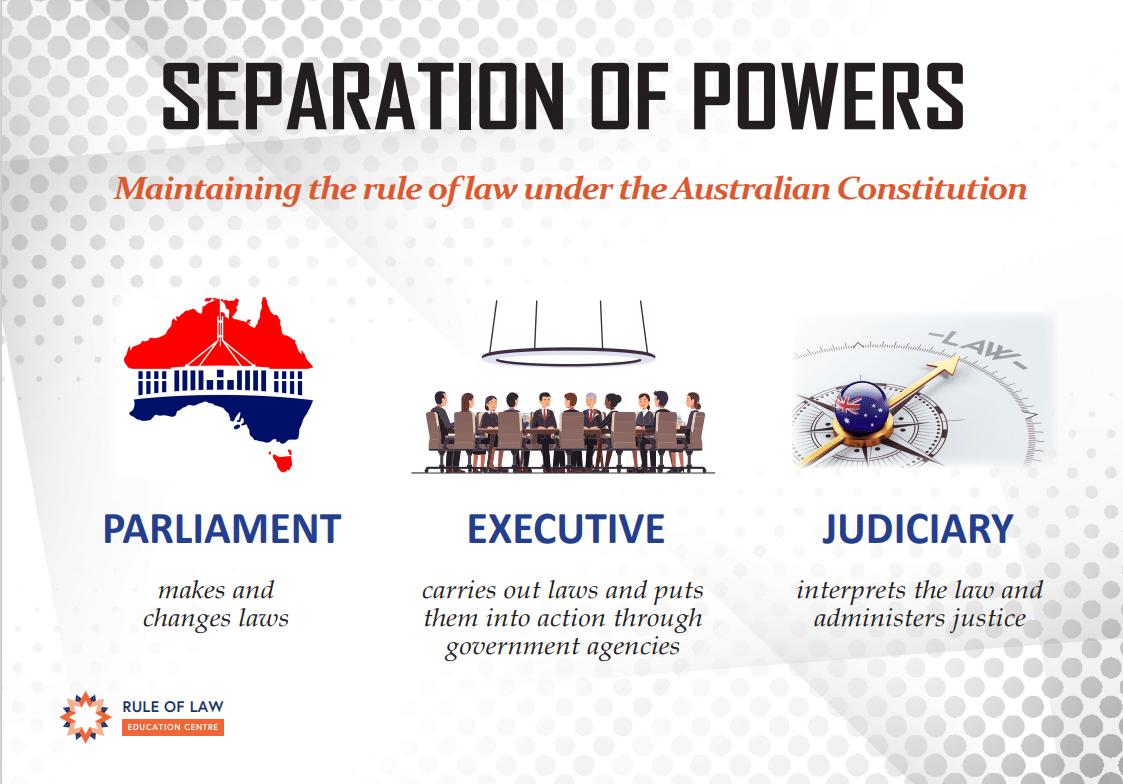

Before going further into the judgment, it is important to understand the separation of powers.

The separation of powers is traditionally understood as the separation of government authority and power between three different branches: the legislative, the executive, and the judicial. The most commonly cited example of this separation is the federal government in the United States. In that country, the President represents the executive, the Congress represents the legislature, and the Supreme Court, and other federal courts, represents the judiciary. There is very little overlap between the powers and roles of the three branches, each of which is supposed to function as a check and balance on the others.

In contrast, the traditional British style of government, called the ‘Westminster’ system, after the palace in which the UK Parliament is held, does not have a strict separation of powers. In this system, the executive and the legislative branches are very much interlinked; indeed, the executive branch (the Prime Minister and cabinet) are drawn from the legislature, and the Lord Chancellor in the UK used to be a member of all three branches, being simultaneously a senior judge, speaker of the House of Commons, and a member of cabinet.

Australia is in the strange position of having inherited the British style of government, but with a Constitution that separates out the three branches of government, like the American Constitution. Importantly, the Australian Constitution also limits the power of the legislative branch to certain areas. That is, Parliament cannot just make laws about whatever it wants – it must be able to identify a provision in the Constitution that gives it the power to make that particular law.

Chapter III of the Constitution

The Australian Constitution is organised by chapter. Chapter I deals with the legislative branch, Chapter II deals with the executive branch, and Chapter III deals with the judicial branch.

After considering this structure of the Constitution, and the limited powers expressly granted to Parliament, the majority of the High Court decided that if Parliament wanted to give particular powers to a federal court, it must be able to point to something in Chapter III that allowed them to do that. As the majority said:

When an exercise of legislative powers is directed to the judicial power of the Commonwealth, it must operate through or in conformity with Chapter III.

In other words, there was no other source of power in the Constitution that would allow Parliament to confer certain functions on a court. If Parliament wanted to confer both arbitral and judicial powers on the Arbitration Court, they must be able to point to something in Chapter III that allowed them to do so.

The majority found that there was no way that Parliament could do this. There was nothing in Chapter III that authorised the conferral of arbitral powers onto a federal court:

Chapter III does not allow powers that are foreign to the judicial power to be attached to the courts created by or under that chapter for the exercise of the judicial power of the Commonwealth.

As a result, the High Court said that the Arbitration Court could not exercise both its arbitral functions, and judicial functions, like granting injunctions, or finding people in contempt. Given that its dominant function had been as a arbitral tribunal – as discussed above – the High Court said the Arbitration Court’s judicial powers could no longer be validly exercised.

The combined effect of the Boilermakers’ case has often been expressed as follows:

- Only Chapter III courts can exercise the judicial power of the Commonwealth; and

- Chapter III courts cannot exercise any non-judicial power.

After Boilermakers’

Boilermakers’ was the high point of the separation of judicial power in Australia. Its strict interpretation has been progressively relaxed over the last 60 years.

The biggest exception to the Boilermakers’ principle is the “persona designata” rule. This rule allows non-judicial functions to be conferred onto federal judges in their personal capacity, rather than in their capacity as a judge. This is the exception that allows federal judges to act as the head of administrative tribunals like the AAT, or authorise telephone interceptions.

Although this rule has been criticised as artificial and confusing, it still provides an important exception from the strict Boilermakers’ principle.

State courts have also been immune from the strictness of Boilermakers. Since the Court’s reasoning in that case was based on the Constitution, it follows that the States, who have their own constitutions, do not necessarily have to abide by the same principle.

Nevertheless, in a series of decisions beginning with the Kable case, the High Court has said that State courts cannot be vested with non-judicial powers that are incompatible with the exercise of judicial power. This includes powers that might undermine public confidence in the judicial system. However, this incompatibility doctrine is a whole other field of law, beyond the scope of this article.

Boilermakers’ and the rule of law

The Boilermakers’ case represented an important step in the development of Australia’s understanding of the separation of powers. Its strict rule has been criticised as unnecessarily rigid, but it has remained the guiding light for future courts considering judicial independence and integrity at the federal level.

Perhaps the true importance of the separation of judicial power was recognised centuries ago by Montesquieu, the French lawyer and philosopher credited with first describing the separation of powers:

There is no liberty, if the judiciary power be not separated from the legislative and executive. Were it joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control; for the judge would be then the legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with violence and oppression.

It is a caution that is still relevant to us today.

Further reading

‘R v Kirby; Ex parte Boilermakers’ Society of Australia‘ (1956) 94 CLR 254

‘Attorney-General of Australia v the Queen‘ (1957) 95 CLR 529, the Privy Council appeal of the Boilermakers’ case, which reaffirmed the High Court’s position

‘Executive toys: Judges and non-judicial functions‘, the Honourable Robert French, Chief Justice of the High Court

‘Wilson and Kable: The Doctrine of Incompatibility – An Alternative to the Separation of Powers?‘, Professor Gerard Carney

‘On Being a Chapter III Judge‘, the Honourable Michael Parker, Justice of the Federal Court

Further Rule of Law Resources

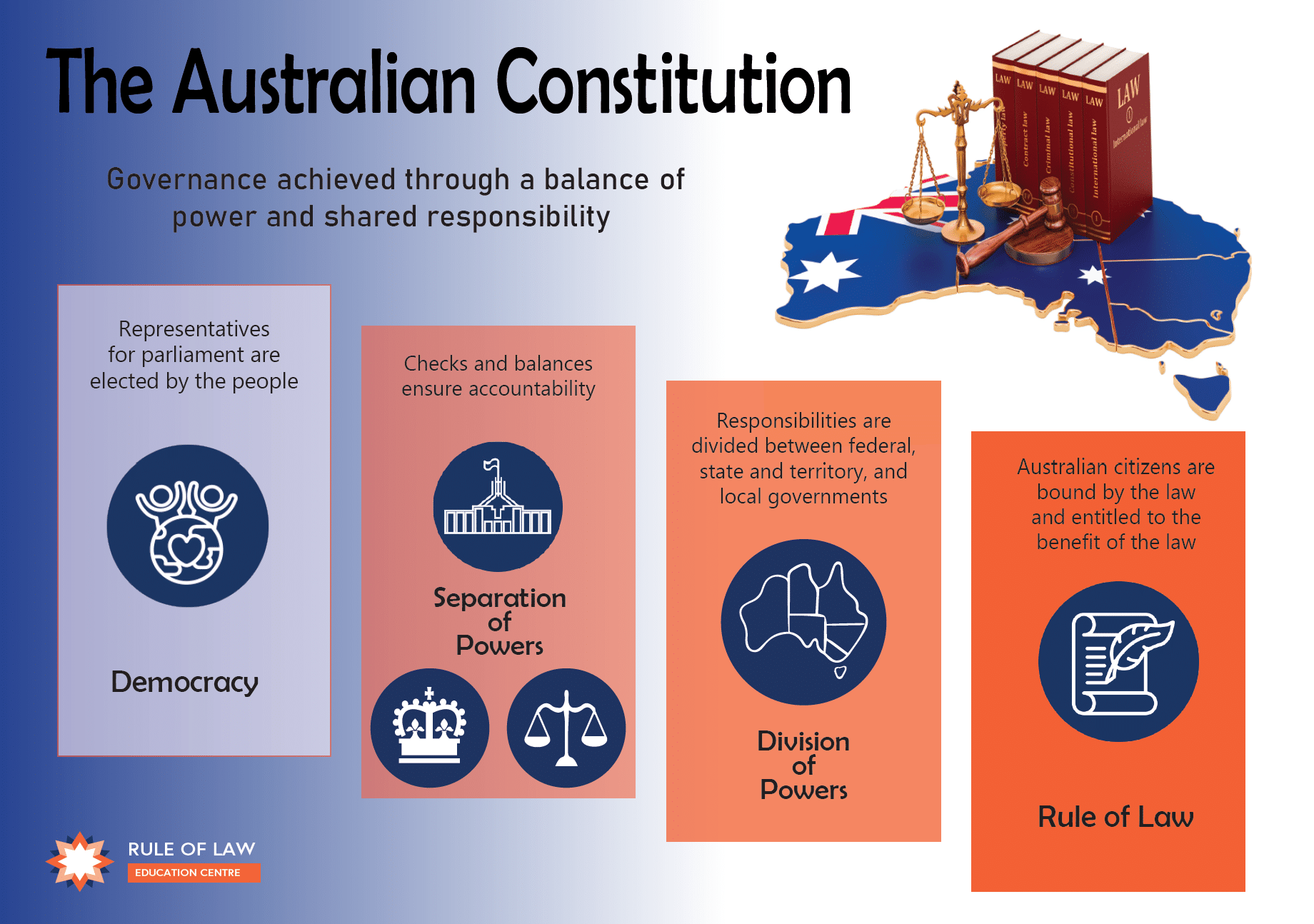

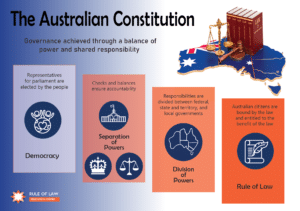

The Constitution ensures Australia operates under the rule of law with power shared between the peoples’ representatives in federal, state and territory parliaments; the executive council, including the Queen’s representative – the Governor General; and the judiciary

The separation of powers ensures that power is not vested in a single entity, but instead is disbursed across three branches of government

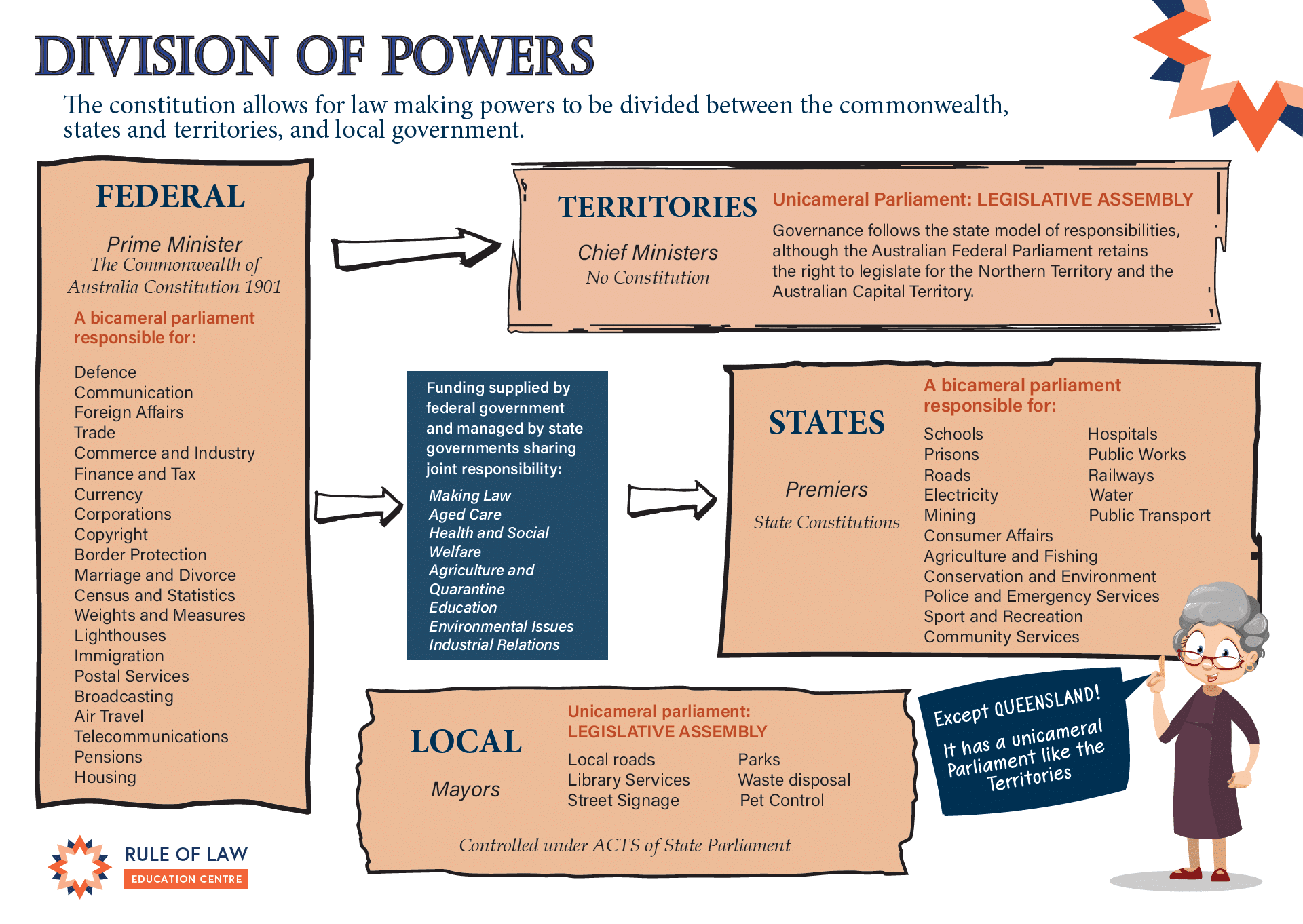

The federal system of government means that power is shared between the federal, state and territory governments according to the division of powers

Human rights are protected by democracy with only a few express rights in the Constitution.