What Safeguards does a Federal ICAC need?

Designs for the proposed National Integrity Commission

Benchmarks that could help you reach your own conclusions when the government unveils its plans.

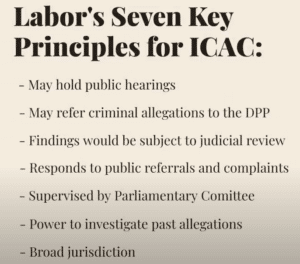

We already know a a little about the commission’s key functions thanks to seven design principles that have been made public by the Labor Party.

The key point is that it will conduct public hearings and make public findings of corruption, just like its counterpart in NSW – the Independent Commission Against Corruption (‘ICAC’).

We also know that after declaring people corrupt, it will follow the NSW ICAC practice and refer some of those people for possible criminal prosecution.

We also know those public findings will be subject to judicial review – again like ICAC in NSW.

But what we don’t know is whether the government has found a way around the problems that this structure has caused in NSW.

So here’s what to look for:

1. Rules of Evidence

The first issue is whether the new Commission will be empowered, like its NSW counterpart, to ignore the rules of evidence. And will people be declared corrupt over conduct that, under the normal law, does not amount to wrongdoing?

If that proves to be the case, it is worth considering the fairness of the apparent intention to limit appeals to judicial review – which focuses on the narrow question of whether there has been an error of law.

Does the government, in other words, plan to follow the NSW model and refuse to allow the merits of public findings of corruption to be tested on appeal?

If that is what emerges, it would mean the Commission’s legal errors could be corrected, but errors of fact would remain in place.

Like all human organisations, the new Commission would inevitably be subject to error. But if those mistakes infect a public finding of corruption, simple fairness requires that a form of redress should be available to those who are adversely affected.

2. The Definition of Corruption

The most important part of the Commission will be the definition of corruption. If that is clear, the propensity for error will be minimised.

But if it is vague and complicated – which is the case with the definition used by ICAC in NSW – the risk of injustice will be greater.

The need for a clear definition of corruption will be all the greater if the Commission follows NSW practice and is empowered to declare people corrupt for conduct that is not unlawful.

Keep in mind that ICAC misunderstood the definition in the NSW legislation so often that the government of that state enacted special legislation in 2015 to validate its mistakes.

Conduct by the NSW Commission that was unlawful one day was rendered lawful the next.

3. Resolving Conflicting Findings

Another test for the government’s plan is whether there will be a way of resolving conflicting findings. What happens to people who are publicly declared corrupt by the new Commission but are later acquitted when brought before the courts?

NSW has ignored this problem – which means people who are entitled to a presumption of innocence in that state are also subject to corruption findings that remain on foot.

The lesson from NSW is that conflicting findings are inevitable if the new Commission is exempted from the rules of evidence – and can impugn those who have broken no laws.

The challenge is to find a way of avoiding those conflicts so the community receives clear signals about the sort of conduct that is permissible, and impermissible.

What will happen, for example, if independent prosecutors examine the material assembled by the new Commission and find there is not even enough evidence to prosecute those who have already been declared corrupt?

The experience in NSW shows that merely complying with the law might not be enough to keep people out of trouble – and that could include those in the private sector who have had business dealings with the government.

Unless the reach of the new Commission is closely confined to the public sector, those in business who have broken no laws could still be dragged into a public hearing and declared corrupt over their contact with the public sector – even if the courts later rule that no laws were broken.

Unless this problem is addressed, the public sector and the private sector could be heading for trouble.

If the merits of a corruption finding cannot be tested, and the definition of corruption is vague, those in business might need to carefully consider their position before engaging with anyone who is subject to the jurisdiction of the new Commission.