Did Democracy die during the pandemic?

Covid, Law-makers and our Liberty

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated drastic laws to preserve the health and livelihood of the nation. Though lawful, many of the Public Health Orders have lacked public scrutiny and the important checks and balances in a democracy that are critical for such extraordinary law-making powers.

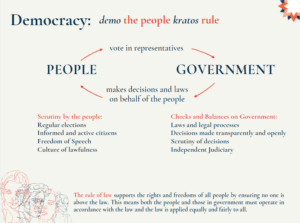

In a democracy the people rule.

They rule by voting in representatives to parliament who make decisions and laws on their behalf. In a democracy, rights and freedoms are protected through;

- parliamentary scrutiny,

- regular elections,

- informed and active citizens, and

- checks and balances on government power, including transparent law-making and scrutiny of decisions.

From 2019-2021, Australia has seen the establishment of new institutional frameworks in response to the pandemic, such as powerful bodies of health authorities that are able to determine the timing and magnitude of state-wide health orders. While the nation has made great efforts to comply with the orders of health authorities, Australia has also seen civil disobedience on the streets of Sydney and Melbourne through reoccurring protests, clearly evidencing a level of distrust from our citizens toward our government.

We, as citizens, must question whether or not these new institutional frameworks and systems of rulemaking are fit for purpose, and whether or not they align with our nation’s democratic values.

The team at Rule of Law Education Centre interviewed George Williams from the University of New South Wales to discuss law-making and liberty during the pandemic. This interview is the basis of this resource and considers if democracy in Australia died during the pandemic.

Mr (Roy) Royal Butler, MP Member of the Legislative Assembly, Member for Barwon and Member of the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party said February 2022, in regards to an e-petition sent in 2021:

It might be argued that the unprecedented public health emergency necessitated unprecedented measures, suspending parliament was actually counterproductive because it narrowed the governments vision at a time when they should have been more open to a wider range of solutions for the crisis and to be more transparent to the public who are confused concerned about what was happening and who needed to be better informed….

By suspending parliament for as long as it did, the government undermines our democracy and it went further than that because the papers were held up for months making a mockery of the government claims to be transparent and accountable- one of the fundamental principles of democratic government, is that the incumbent administration opens itself up to the scrutiny of other elected representatives.

It allows voices from outside the party in power to call the government to account, protections to point out the problems with what it what it is doing and draw attention to any other oversights. When a government ignores these checks and balances it can run into serious problems the exchange of ideas is a vital part of the democratic process it allows a range of voices to be heard and points of view argued as a result the ideas that are best for the people and the running of the state can emerge it is also essential to avoid problems such as self interest or blind prejudice creeping into public administration.

The role of government in a democracy is to make decisions and laws on behalf of the people

1. The role of Parliament is to make laws. In some circumstances this power can be delegated

It is the responsibility of Parliament to make laws on behalf of the people they represent. They may seek advice from experts such as the police, health advisors or the army BUT it remains the role of the parliament to make the final decision regarding laws that are made.

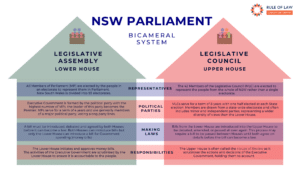

In NSW, the two houses of parliament provide a system of checks and balances to ensure laws are made openly and transparently by the people through their representatives of parliament.

These laws are debated and deliberated by both houses before being passed to ensure they are legal, necessary, proportionate and non-discriminatory. Together, the two houses hold the government to account, acting as a safeguard against any arbitrary or excessive use of government power.

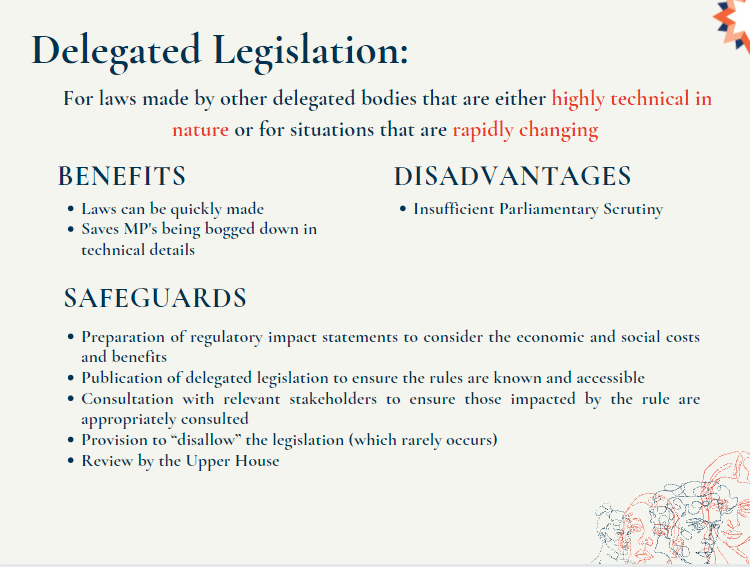

The Parliament has many bills to consider and debate, therefore some laws contain provisions that allow other bodies to make rules and laws without having a bill being passed and agreed by both Houses of Parliament before becoming law. Laws and rules made by other delegated bodies are called delegated or subordinate legislation. Delegated legislation is used for laws that may be highly technical in nature, or in situations that are rapidly changing and there is not enough time for the bill to go through the lengthy process of debate and deliberation in both Houses.

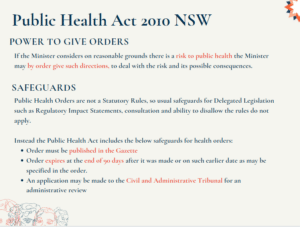

The lockdown laws and restrictions in NSW were lawfully made through Public Health Orders under the Public Health Act 2010.

Whilst these laws are clearly published, they are passed with very little scrutiny or accountability appropriate for laws with such a significant social and economic impact. As they are not considered ‘statutory rules’, the safeguards for Delegated Legislation, as detailed in this poster, do not apply.

Public Health Orders have 3 specific safeguards according to the Public Health Act;

Public Health Orders have 3 specific safeguards according to the Public Health Act;

1. Orders are published

2. Orders expire after 90 days (somehow NSW has been under rolling Health orders for almost 600 days!!)

3. Appeal to the Administrative Appeal

As George Williams explained in our interview, these Health Orders may be lawful but the safeguards provide little protection for bad decisions being made;

“The Federal Health Minister, once you have these kinds of emergencies can make any direction, can make any declaration he thinks is necessary to meet the threat of the pandemic. Not only that, his declarations override any other law, including laws made by Parliament, and Parliament is prevented from disallowing any of his declarations. That’s as close to a dictatorship as you can get.”

Is the Public Health Act a good law?

- Does the Public Health Act erode the powers of the Parliament to make laws?

- Do the provisions for making Health Orders provide too great a law making power to non-elected representatives?

- Does it provide powers to the Health Minster that are too broad and have little contemporaneous scrutiny or transparency?

- Do the safeguards provide sufficient checks and balances to ensure the powers are legal, necessary, proportionate and non-discriminatory?

- If we face another state or national emergency, will we again hand over broad law-making powers with little scrutiny and accountability?

2. Parliament’s role is to scrutinise and hold government to account

In a democracy, the Parliament’s role is to ensure accountability and transparency for all laws made. This involves scrutiny, both at the time the law is made and when it is in force. To do this, Parliament must uphold sitting dates so the Government can be held accountable in question time, for health officials to explain their recommendations, for committee inquiries to consider the impact of the laws on the people and the economy, for petitions to be tabled, and for the opportunity to disallow delegated legislation.

“The task of the Parliament is not only to pass laws but also to watch and control the government through questions to ministers and through debate in the House and committee inquiries. In that sense, securing the accountability of the government is the very essence of responsible government”

-NSW Legislative Council Practice

During the Delta outbreak, 2 worrying things occurred:

a. NSW Parliament did not sit for 110 days

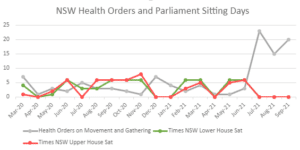

NSW Parliament did not sit between 24 June 2021 to 12 October 2021 (almost 1/3 of the year) despite the influx of health restrictions being mandated as seen in the graph below.

(Source: https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/Pages/sitting-day-calendar.aspx)

When Parliament does not sit, we are left bereft of the most important accountability mechanism of government- Parliament and Question Time. It is not acceptable to remove these forms of scrutiny and accountability.”

– George Williams

When Parliament does not sit there is no debate or question time, and no review. Resulting in failure of our democracy.

b. The Upper House (the House of review) was stopped from sitting

Attempts by Members of the Upper House to re-convene Parliament on 7th September 2021 after not meeting since March 2021 were blocked by the government.

Robin Speed from the Rule of Law Institute explained in his article ‘Upper House Stopped from Meeting: A Constitutional Crisis in NSW‘:

“The NSW Government has created a constitutional and democratic crisis by preventing the Upper House of Parliament from meeting.

With the unprecedented encroachment on our freedoms, if ever there was a need for the Upper House to scrutinise the Government, it was now. It shows the extent of the Government’s avoidance of scrutiny, that it has pulled this trick. Without the House meeting Bills cannot be passed, inquiries heard and scrutiny of the Government cannot take place. Business of the Government will slowly wind to an end. None of this appeared to trouble the Government when it decided to pull a trick, like you rarely find in business; not for a Minister to be present in the House as required and then to argue as the Minister was not present under the rules the meeting cannot proceed, is a bit rich.”

-Robin Speed

Parliament is an essential service and must sit.

Elected representatives have let democracy down. There needs to be some accountability for the 110-day hiatus and we must make sure it never happens again.

3. Democracy requires informed and active citizens

“The health orders are lawfully made, but it’s really a question of community confidence and appearance that seems to be problematic”

– Chris Merritt

In the circumstances of the pandemic, it is understandable that our nation’s citizens have focused on their attention on health, finances, and basic needs, rather than scrutinising the absence of Parliamentary sittings. As stated by George Williams, “fear dampens the desire of people to know more,” causing citizens to place blind trust in our government out of desperation.

Despite the fear and anxiety instilled by the pandemic, it should be a priority for the people to remain vigilant in assessing the government’s actions. When there is no citizen engagement and scrutiny, our nation ceases to have a democracy.

- Citizens need to be informed. People will support laws if they understand the basis and justification for the law, and consider the response to be proportionate and appropriate.

- Citizens must have opportunities to be active. During the pandemic, MPs were flooded with emails and calls to their offices from constituents, desperate to have their voice heard. E-Petitions were lodged with Parliament from concerned citizens. However, these peaceful mechanisms were pointless when Parliament did not sit. No wonder people resorted to protesting in the street when that was the only option left for people to have their voice heard!!

The decline in civic education and understanding of civic responsiblity in Australian society has contributed to the failings of our democracy during the pandemic.

This issue was recognised in the Rule of Law’s Submission to the ACARA Curriculum Review, that highlighted how many Australians currently do not understand or value the key beliefs that underpin the rule of law in our parliamentary democracy. This must be significantly improved. Unless we change the curriculum we will continue to create a generation of students who do not understand nor value their role in participating and engaging productively in Australian society.

Does NSW need a Charter of Justice?

The lack of Parliamentary sittings, as well as the absence of more rigorous checks on the enactment of health orders, poses a threat to democracy by placing powers in the hands of the nation’s health authorities.