By Rebecca Ananian-Welsh, The University of Queensland

The government introduced its third set of national security laws last week. The Counter-Terrorism Legislation Amendment Bill (No 1) 2014 valuably empowers the Parliamentary Joint Committee of Intelligence and Security (PJCIS) to review changes to the list of declared “terrorist organisations”.

More significantly, and disturbingly, it expands the existing control order regime and changes the role of Australia’s international security agency, ASIS, in a way that may facilitate targeted killings.

This year has brought the biggest changes to national security law since 2005. These amendments cement Australia as the nation with perhaps the most counter-terrorism laws in the world.

The two acts already passed in 2014 have brought about a vast set of reforms. These include the controversial foreign fighter provisions, enhanced powers for ASIO and legal immunity for ASIO officers acting in the course of certain operations.

The bill introduced last week is much briefer and its reforms more focused. Nonetheless, it raises serious questions for the PJCIS review to consider.

Could Australians be targeted for killings?

The bill does not mention the targeted killing of Australians overseas. But it does introduce amendments to the Intelligence Services Act 2001 that could make this outcome possible. The bill would change the role of ASIS by stating that it has the function of providing assistance to, and co-operating with, the Australian Defence Force (ADF).

ASIS itself is prohibited from engaging in violence against persons. However, the bill empowers the minister to authorise ASIS, in its new role, to assist the ADF by undertaking activities that will directly affect an Australian person, or even a class of Australian persons. The activities of the ADF may, of course, include personal violence.

The proposed amendments reflect an appropriately high concern for the preservation of safeguards. The most crucial of these is the authorisation of the minister, except in strictly limited circumstances, and the involvement of the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security. After all, there is little scope for courts or parliament to be involved in authorising or reviewing such operations. It also makes some sense that Australia’s international intelligence agency should have some role in assisting the ADF.

But the bill also raises the spectre of Australian forces harnessing intelligence on Australians overseas to engage in targeted killings.

Targeted killings by state forces have been a subject of extensive global controversy. They challenge principles of international law, as well as rule of law values.

Here in Australia, where the death penalty has been abolished, the targeted killing of Australians overseas presents serious questions that go to Australian sensibilities, morality and values. Targeted killings may also prove ineffective and ultimately undermine counter-terrorism efforts, as renowned counter-insurgency expert David Kilcullen recently argued.

The introduction of the bill highlights the need for a conversation to be had in parliament and in our communities about whether Australian forces should engage in targeted killings. And, if so, on what terms? These may not be easy questions; they deserve careful deliberation and debate.

The introduction of the bill and its consideration by PJCIS present a rare opportunity to debate the actions of our intelligence services overseas, and to design appropriate limits on these actions.

Expanding control orders

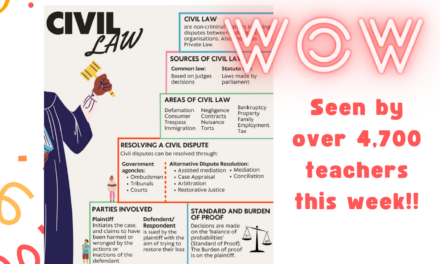

The bill also expands the existing control order regime. Control orders are civil orders issued by federal courts. They permit a vast array of restrictions and obligations to be placed on a person for up to 12 months for the purpose of protecting the community from terrorism.

Control orders are highly controversial, not least because they infringe liberty outside the criminal process. The scheme has been used only twice in nine years, each time in controversial circumstances.

The Independent National Security Legislation Monitor recommended the provisions be repealed and the High Court’s 5:2 decision upholding the validity of the orders has attracted scholarly criticism. The provisions were originally designed to sunset after ten years (in 2015).

The bill proposes multiple changes to the control order scheme. These include the welcome stipulation that a court must consider the person’s need to prepare his or her case when setting the date for the control order hearing. However, the bill also waters down safeguards attached to the scheme and expands its potential operation.

The bill retains the requirement that the attorney-general consent to each control order application. However, it would remove the requirement that the minister be presented with comprehensive information about the order. For instance, the attorney-general would no longer necessarily be informed of previous or related applications, or of any factors that may weigh against the order being issued.

It is far from clear why the important safeguard of the attorney-general’s consideration of the control order application should be diluted.

Second, the bill would amend the court’s role by no longer requiring it to assess each obligation and restriction requested in the control order application. Instead, the court would only be required to weigh the control order as a whole against the issuing criteria.

It is not clear how this set of amendments would impact the court’s reasoning in practice. One might imagine that a court would nonetheless consider each term of the order separately. Therefore it is difficult to see why the amendment is necessary.

The change would also make the court’s role less clear-cut. It may even result in less detailed scrutiny of the control order’s provisions.

Finally, the bill would add two new grounds on which control orders may be issued. Namely, where a court is satisfied that the order would substantially assist in preventing support or facilitation of a terrorist act; or that the person has provided support for or facilitated the engagement of hostile activity in a foreign country.

This presents a serious expansion of the scheme. At present, orders may be issued only to assist substantially in preventing terrorism, or when the person has been involved in training with a terrorist organisation.

Firstly, the proposed amendment expands the operation of control orders beyond “terrorism” to encompass hostile activities overseas. Secondly, including “support” or “facilitation” extends the scope of activities that may bring a person within the control order regime to, for example, packing a suitcase or buying a plane ticket to go overseas for violent purposes, or perhaps making statements on social media that may be construed as supporting hostile activity overseas.

The potential impact of this final amendment deserves careful consideration when the bill is considered by the PJCIS and is debated in parliament. It is clear that the expansion of control orders into new territory heightens the need for safeguards such as the attorney-general’s consent and rigorous judicial scrutiny. This suggests that the safeguard provisions should not be amended as proposed.

Democratic values at risk from within

This third set of national security reforms contains many troubling proposals. These should not be hastily enacted.

It is all too easy to be swept up in the array of national security laws being passed at the moment and to overlook a shorter bill such as this. This is particularly the case as fear of Islamic State and domestic terrorism increases, and as national security measures usually attract bipartisan support from the major parties.

Nonetheless, Australians must be vigilant to ensure that the liberal democratic values we are striving to protect from terror are not themselves compromised by our counter-terrorism laws.

Rebecca Ananian-Welsh does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Republished under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article