Paul Kelly: The Voice

Robin Speed Memorial Lecture: Rule of Law Series

1 June 2023

Other Resources from the Rule of Law

Transcript of Paul Kelly’s Speech at the Robin Speed Memorial Lecture

Distinguished guests, ladies and gentlemen, it is a pleasure and honour for me to deliver this Robin Speed Memorial Lecture. I thank my colleague and legal affairs writer for The Australian, Chris Merritt, for the invitation.

I congratulate the Rule Of Law Institute for its stance and its activity in promoting freedom of speech, presumption of innocence and the separation of powers -such activity much needed in Australia today. One only needs to consider the high profile injustices we have witnessed – ranging from Christian Porter to George Pell – to appreciate this.

As founder of the Rule of Law Institute, Robin Speed had a profound and clear vision of the principles that should guide law in this country. I acknowledge the tribute to him from Malcolm Stewart tonight.

Let me begin with a story.

In 1965 a delegation of Aboriginal leaders came to Canberra for a meeting with Prime Minister Menzies. It was a brief encounter between two alien worlds. Menzies for most of his prime ministership had displayed little interest in Aboriginal affairs. A young Faith Bandler was one of the activists and recounts what happened: “He (Menzies) had no idea there was such suffering in this country, no idea whatsoever. He started off by offering drinks and he said to Oodgeroo, who was then Kath Walker the poet, and whose work he had read, ‘What will you drink?’ She said, ‘Well, prime minister, if you lived in Queensland and offered me a drink, you’d be put in jail.” And he hesitated and I could see, we could all see, he was quite shocked – this woman who had created these beautiful poems that he’d read was deprived of having a drink.”in

The Aboriginal delegation did not convince Menzies at their meeting.

Our worlds are no longer alien. The lack of understanding is different – but it still runs deep.

In 1967 the referendum was passed to remove the exclusion of Aborigines from the census and to allow the Commonwealth to make laws for the Aboriginal people. As we know the Yes vote was 90.8 per cent. It was a vote I believe, on the part of most people, to give Indigenous peoples a ‘fair go’ after their exclusion for so long. It was an act of goodwill from a less politicised age.

There were two inevitable consequences. The referendum raised a new set of expectations and demands from Aboriginal people. Far from offering a basis on which to settle Aboriginal policy, it guaranteed the real and inevitable battle was about to begin. Second, in the 1967-72 period a new idea would emerge arising from the sense of Aboriginal dispossession – a claim for separate Aboriginal rights.

This was not just a claim for equal rights. It constituted a new force whose time had come. That claim for separate Aboriginal rights within Australian democracy remains alive and far more powerful today. That bid rests upon many thousands of years of Aboriginal occupation of this continent; it has moral force and it is an irresistible political movement. The real issue is what forms this claim takes, how it is managed and negotiated and what our overall polity agrees on.

Over the past 30 years a series of milestones have been reached and passed. This story is a mixture of legal, political, symbolic and practical issues. It has been driven by a series of outstanding Indigenous leaders from all parts of our country.

We like to think Indigenous rights should be built on bipartisan foundations. That’s desirable but it’s not always possible.

The Native Title Act, flowing from the historic High Court decision, was deeply divisive in the national parliament. After the court’s Mabo decision, Prime Minister, Paul Keating said: “The High Court rejected a lie and acknowledged a truth.” The Coalition, led by John Hewson, opposed Keating’s bill and declined to consider amendments. Hewson’s message was: “You have sold out all other Australians who are going to be significantly worse off.”

There were many conclusions but let me highlight two. First, Keating negotiated with Indigenous leaders and modified some of their demands. He showed that the role of the prime minister was to meet and negotiate with Indigenous leaders, not merely to accept ambit demands.

Second, Native Title did divide the Nation. It saw a significant rift between Labor and the Coalition and seeded mistrust for years between the future Howard government and the Indigenous leaders in this country. It contributed in part to the magnitude of Paul Keating’s defeat at the 1996 election. The reality is the political conflict and disagreement is embedded in the long process and debate over Indigenous rights. This issue is never going to be plain sailing. It won’t always be easy. The Voice is the latest example in this conflict.

Regardless of whether the Yes or the NO vote prevails, the country will be divided over the Voice and it will need to manage the division. The legacy will be serious. However, I think Australians will be able to manage the outcome. That is the sort of people we are, Indigenous and non-Indigenous. We must never forget our capacity to get on together and live together.

Let me make a few points about the Voice and the current debate.

First, the way the Voice is being presented represents a fusion of two separate ideas – the claim for Indigenous recognition in the Constitution, the demand John Howard accepted before the 2007 election, and the creation of the Voice. The Voice is an idea given formal expression in discussion several years ago involving a number of people including Noel Pearson, Greg Craven, Anne Twomey, Julian Lesser and Damien Freeman.

These two ideas, Indigenous Recognition and the Voice, don’t have to be together. They don’t automatically fit together. They were brought together for a specific purpose: to give recognition a substantial meaning in terms of constitutional power. On the other hand, there could be a referendum on constitutional recognition and, quite separately, a Voice could be created by legislation, to be tested or revised by the Parliament and the people who would have the chance to see how it worked.

The second point to make about the Voice is that the model evolved over time. The start was very different to where we are now. The 2017 Referendum Council Report recommended “that a referendum be held to provide in the Australian Constitution for a representative body that gives Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders a Voice to the Commonwealth Parliament.” Eighteen months later three of the key leaders from Uluru – Pat Anderson, Megan Davis and Noel Pearson – proposed to a Parliamentary Committee that there be a First Nations Voice to present its views to government as well as to the Parliament. As my friend and legal scholar, Father Frank Brennan, has pointed out, this was a major change. The suggestion was that the voice be able to present views not just on proposed laws made under s52 (xxiv) but on “all matters relating to Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.” This submission was received after the cutoff date.

Father Brennan has drawn attention to the committee report: “The committee has received 18 models of potential constitutional amendments. The fact that there are so many different provisions proposing to constitutionalise the Voice and that a new provision was suggested in a late submission received by the Committee on the 3rd November 2018, nearly two months after submissions had closed, indicates that neither the principle nor the specific wording of provisions to be included in the constitution are settled. More work needs to be undertaken to build consensus on the principles, purpose and text of any Constitutional amendments.”

In short, there needed to be an extensive process to try and reach consensus on the best model for the Voice. But that did not happen.

The third point I want to make about the Voice is that the rejection in principle of the Turnbull cabinet was a decisive event. In his biography ‘A Bigger Picture’ Malcom Turnbull recalls a meeting he hosted in November 2016 as prime minister with Aboriginal leaders including the four then Indigenous members of parliament. Noel Pearson said that he was expecting the Uluru Conference to recommend there be a change to the Constitution to establish a Voice which would be a national assembly composed of elected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In his memoirs, Turnball says: “A general discussion followed and there wasn’t a lot of support for the Voice around the room. Shorten and I both expressed the same view. We weren’t comfortable with the Constitution establishing a national assembly open only to members of one race, and moreover we both said we thought it would have no prospect of success in a referendum. “A snowball’s hope in hell” as Bill had previously said to me.’

Subsequently the Turnbull cabinet assessed the proposal for the Voice. That cabinet contained Barnaby Joyce, Josh Frydenberg and Peter Dutton among others. Turnbull said the decision they reached was unanimous. The announcement said: “The government does not believe such an addition to our national institutions is either desirable or capable of winning acceptance in a referendum. Our democracy is built on the foundation of all Australians citizens having equal civic rights, all being able to vote for, stand for and serve in either of the two chambers of our national parliament, the House of Representatives and the Senate. A constitutionally enshrined additional representative assembly which only Indigenous Australians could vote for or serve in, is inconsistent with this kind of fundamental principle… The government does not believe such a radical change to our constitution’s representative institutions has any realistic prospect of being supported by a majority of Australians in a majority of states.”

Often today you hear people talk about conservative opposition to the proposed Voice. This cabinet position was not conservative opposition. It was based upon the classic principles of liberalism that have underpinned liberal democracies for many decades in Australia and in other countries. Of course, most conservatives would subscribe to these principles, but these are liberal principles.

It has been fashionable for many years for political commentators to say that it was the conservative wing or the extreme right wingers in the former coalition government that opposed the Voice. That is inaccurate. It is inaccurate on the basis of the formal statement made by Turnbull as prime Minister. The reality is that the Liberal Party and the Coalition have never felt any political ownership of this idea. It has been opposed by Tony Abbott, by John Howard, by Malcolm Turnbull as Prime Minister, by Scott Morrison and now is opposed by Peter Dutton, as the leader of the Opposition and Liberal Leader. I have written it is no surprise Dutton took this stance given the history that I have just outlined. The position the Morrison government took to the last election was that there should be no Constitutional enshrinement of the Voice and the focus should be on local and regional voices.

The fourth point I want to make concerns the consistent remark by the Prime Minister Anthony Albanese that this should be seen as an invitation by the Indigenous Peoples to the Australian people to incorporate the Voice in the Constitution. That is, once Indigenous leaders decided what their request was, that request should be put to the People. This is a troubling formulation.

I don’t accept, given the importance of referendums, that it is merely the task of the Australian Prime Minister of the day to act as a “messenger boy” and put a referendum recommended by a particular segment of the Australian community, no matter how important. Albanese is the responsible political agent in this issue. It is his decision to put the referendum, his decision to endorse the wording of the referendum. Why wasn’t there a more open dialogue, negotiation, convention or debate to sort out the best model and best way of proceeding.

The question I am asking here concerns the wisdom with which this issue has being pursued. When one looks at the history of referendums in this country, the Labor Party has put 24 or 25 and has succeeded in passing one – not a good record. What we have seen here is the Prime Minister putting a referendum without any genuine effort to build a broad base of support and political bipartisanship. The judgement the PM has made is that Australia has changed and the rules that have previously applied to a referendum, no longer apply. He might prove to be right. But that is a very big call.

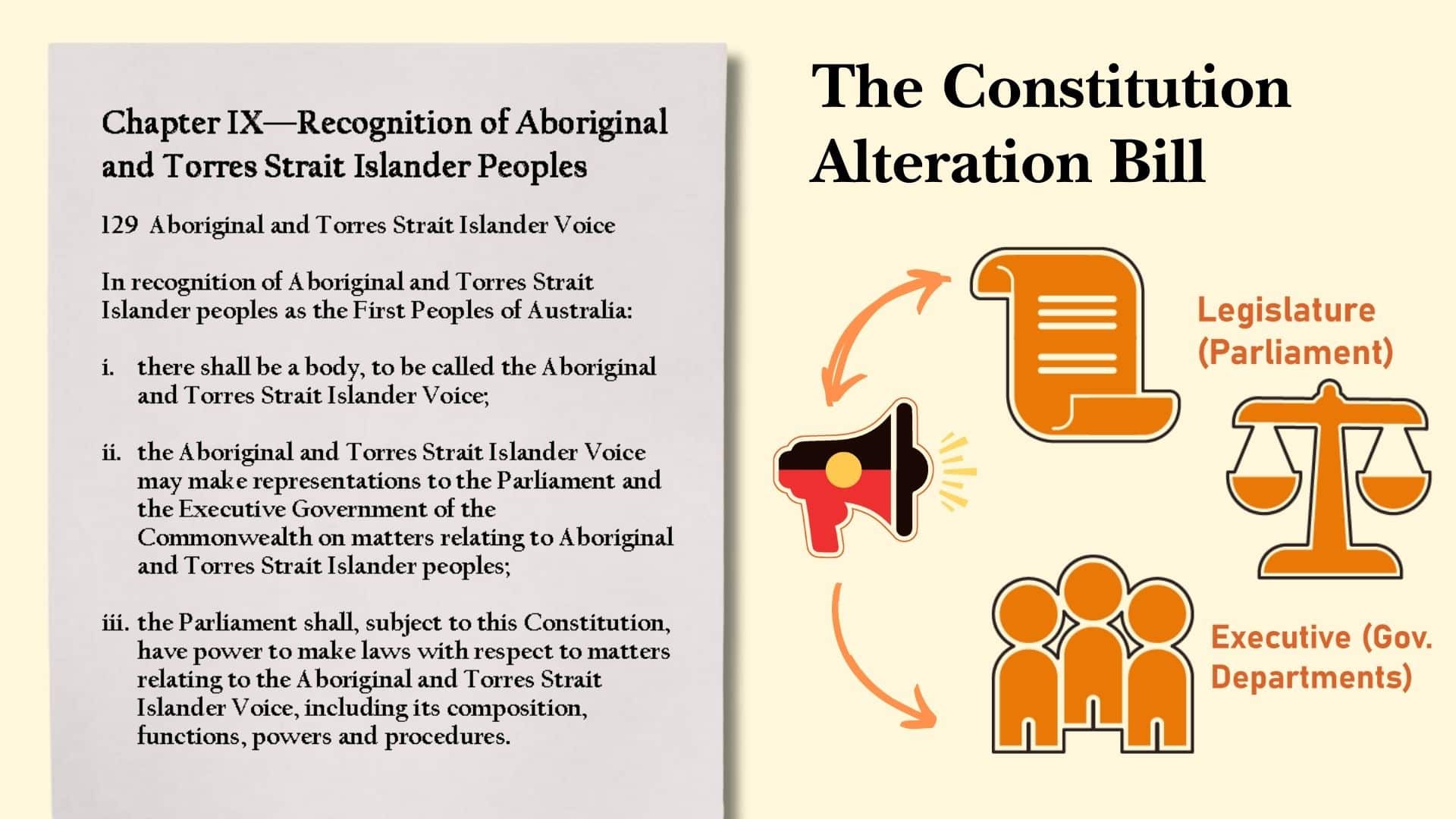

The fifth and final point I want to make is to highlight some defects in the model being proposed. As I see the proposal it is putting into the Constitution a group rights political body with the power to make virtually unlimited recommendations across the board to parliament and executive government on matters that concern not just Indigenous peoples but wider general laws and general executive decision making. Is this the appropriate change in our governance? The reference to the executive means cabinet, ministers, departmental heads and public servants. At the end of the day the High Court will be arbitrating on how these powers are used and how these powers are to be interpreted. We cannot assume what the High Court will decide.

Another issue is the scope of the representations being made by the Voice. The words of the constitutional amendment mean the Voice can make recommendations on issues solely dealing with Aboriginals Torres Strait islanders but also about broader issues of general application since Indigenous peoples are part of the wider community. In short, the Voice can make representations about welfare, resources, land, health, jobs and the economy among many other issues. A few months ago the Prime Minister ridiculed the idea of the Voice giving advice on the Climate Change Safeguards mechanism – yet I would have thought that a responsible Voice if established, would most certainly be giving advice on the safeguard mechanisms. The scope for the Voice should not be under-estimated, for example, it would be able to advise on the date of Australia Day.

The Prime Minister has said it would be a ‘brave government’ that ignores advice from the Voice. This goes to the question of the veto power. The Voice, of course, does not have a veto power over legislation as such. But that is not the point. It will be established as a political body that will have a moral mandate representing the Indigenous Peoples. It will have an authority that comes from being embodied in a new separate chapter in the Australian Constitution, a deliberate decision to shape the way people think about the Voice.

The Voice contradicts the principle of equality of citizenship that enshrines and binds together our nation. The Voice is based on the principle that we have different constitutional rights depending on our ancestry. We need to think about that as a country. And think whether or not we really want that to happen.

The Voice contradicts the principle of equality of citizenship that enshrines and binds together our nation.This is not like passing a law on taxing or industrial relations which another government can change. This is not voting at a general election to put Labor or the Coalition in government for three years. This is a change in the Constitution that, being realistic, would be forever. What will that mean for the unity of our country?

Once created the Voice will be a functioning political body, enmeshed with policy both in the early stages and final stages of policy development. As a political institution, it will be the focus of enormous media attention. Indigenous politicians in the Voice will obviously exploit the media for their own ends and that expectation is entirely proper. Imagine the coverage the ABC would provide to a recommendation from the Voice which directly challenged what the parliament or the government was doing. The Voice will be a new arm in our governance system. The upshot will be that Australians will have different democratic rights based on race and ancestry. Whether the nation and the political system will possess the restraint and wisdom to manage this defies prediction.

ENDS

Robin Speed Memorial Lecture

This lecture is named in honour of the founder of Speed and Stracey Lawyers and the Rule of Law Education Centre, Robin Speed OAM, who passed away in February 2023. The Robin Speed Memorial Lecture will be held annually to coincide with the anniversary of the sealing of the Magna Carta on 15 June.

The purpose of this Lecture will be to provide an inspirational reminder of the contribution made by Robin Speed in promoting and protecting the rule of law in Australia. On establishing the Rule of Law Institute in 2010, Robin hoped “to encourage fellow Australians to stand up and challenge rule of law abuses. This can be done in all sorts of ways, small or large, like making submissions to the government, writing articles, speaking out publicly, attending conferences and working with the Rule of Law Association. The job cannot be left to the courts, where they have limited powers of intervention and any intervention may be too late.”