Claremont Serial Killings Casenote

Watch the judgement of Bradley

Robert Edwards below – ABC News

Facts of the case

Between 1996 and 1997, three young women – Ciara Glennon, Sarah Spiers and Jane Rimmer – disappeared from the popular night spot of Claremont in Perth, Western Australia. The bodies of Ciara Glennon and Jane Rimmer were found and although Sarah Spiers’ body was never found, she is presumed dead. These murders became known as the Claremont serial killings. They captivated and terrified the Western Australia community for over 20 years.

On 22 December 2016, Bradley Robert Edwards was arrested and charged under s 278 of the Criminal Code (WA) with wilfully murdering Ms Rimmer and Ms Glennon. In 2018, Edwards was further charged with the wilful murder of Ms Spiers. Edwards pleaded not guilty to all three charges.

For Edwards to found guilty of each charge, the State must be prove beyond reasonable doubt that:

- the accused killed the named person (Actus Reus);

- that the killing was unlawful and;

- that the accused intended to cause death (Mens Rea)

Actus Reus is the physical act of carrying out a crime. It must be a voluntary act (not under duress) but can also include an omission or failure to act.

Mens Rea refers to the mental state of the accused and means “guilty mind”. To be convicted of wilful murder under the Western Australian legislation, the prosecution must prove that the accused intended to cause the death of his or her victims.

Pre-Trial

In Australia, trial by one’s peers in the form of a jury trial is a constitutional right, under section 80 of the Australian Constitution. However, in every Australian jurisdiction except for Victoria, ACT, Tasmania and the Northern Territory, the accused or the State can elect to apply for a judge alone trial. This typically occurs in situations where there is a concern about impartiality and the need to ensure a fair trial due to the extent of media coverage of the crime. There were four reasons identified why this case should be heard by a Judge alone. These were:

- the extent of pre-trial publicity;

- the likely length of the trial;

- the graphic and disturbing nature of the evidence; and

- the technical or complex nature of expert evidence proposed to be presented.

The Prosecution applied for an order under s 118 of the Criminal Procedure Act 2004 (WA) that the trial be heard by a judge alone. The Defence agreed to this and the order was granted. The case was presided over by Justice Hall without a jury. In circumstances where it is a judge alone trial, the judge is responsible for both ensuring the principles of law and procedure are applied, as well as making findings based on the evidence presented, including giving a verdict.

Note: In NSW, like Western Australia, a person accused of a criminal offence can apply under s 132 of the Criminal Procedure Act 1986 to have the matter heard by a Judge alone. Famous recent cases which received significant media attention but had no way of avoiding the risk of a biased jury by seeking a judge alone trial was the Pell Trial in Victoria and the Lehrmann (Brittany Higgins) trial in ACT. (Read Chris Merritt’s Commentary here about the need for a judge alone option for high profile cases).

The Trial

The Prosecution case relied heavily on DNA, forensic and propensity evidence. The Prosecution presented evidence that the accused’s DNA was found under the nails of Ms Glennon. The prosecution argued that the DNA got there during a violent struggle that occurred sometime shortly before her death. Justice Hall acknowledged the significance of the DNA evidence which he deemed to be critically important to the conviction of Edwards. Justice Hall was satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the Prosecution had proved that the DNA was that of the accused, and His Honour accepted the Prosecution’s argument for how it got there.

The Prosecution presented fibre evidence that established both Ms Rimmer and Ms Glennon were in a VS Holden Commodore car, vehicles which were driven by Telstra employees. The accused was a Telstra employee at the time of the offence, and it was the Prosecution’s case that he drove the car in which the fibres were discovered. His Honour accepted this argument.

Propensity evidence is a form of circumstantial evidence: it is evidence of the conduct of a person or evidence of their character or reputation which supports the view that they tend to act in a certain way.

It was the Prosecution’s argument that three other assaults which the accused had pleaded guilty to provided sufficient evidence that the accused tended to attack women. His Honour said:

“Propensity evidence may be relevant in determining whether a particular person is more likely to be the perpetrator of a crime, but it must be carefully scrutinised and does not alone prove the guilt of the accused.”

This is a very important comment and reinforces that simply because someone has acted a certain way in the past, it does not necessarily follow that a Judge would be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt without further evidence.

Regarding Ms Glennon and Ms Rimmer, Justice Hall opined there were significant similarities between the circumstances of their disappearances and deaths. In Justice Hall’s view, the similarities were so significant as to establish beyond reasonable doubt that the same person killed both Ms Rimmer and Ms Glennon.

His Honour concluded that:

“having regard to the DNA evidence, the fibre evidence and the propensity evidence, I am satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the accused was the killer of Ms Rimmer and Ms Glennon”.

In relation to Ms Spiers death, it was the Prosecution’s submission that even without a body, the similarities between the circumstances of her disappearance and death were so similar to the cases of Ms Rimmer and Ms Glennon, that the only logical conclusion to be drawn was that Ms Spier was killed by the same person. His Honour disagreed with the Prosecution’s argument and instead, reasoned that the similarities were of a more general nature and far fewer than those that existed in the cases of Ms Rimmer and Ms Glennon. His Honour held he could not conclude beyond reasonable doubt that the person who killed Ms Rimmer and Ms Glennon must necessarily be the same person who killed Ms Spiers.

Justice Hall found Bradley Edwards guilty of the murders of Ms Glennon and Ms Rimmer, but not guilty of the murder of Ms Spiers.

His Honour has not yet sentenced Edwards, but the crime of Wilful Murder carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.

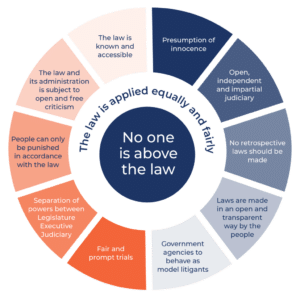

Application of rule of law principles

1. The law is applied equally and fairly

One of the fundamental principles of the rule of law is that the law is applied equally and fairly, so that no one is above the law. The Claremont case drew significant and sustained media attention. It was unique in that it ran for over 6 months and the volume of evidence was enormous. As Justice Hall stated:

“This is a trial like no other. This is a trial like every other. Those apparently irreconcilable statements are both true.”[1]

What this comment reflects is that despite the unusual features of this case, “the fundamental principles that apply to every criminal trial apply equally to this one”. Justice Hall outlined in his judgement that: “the courts do not deliverer different standards of justice” depending on the significance or media attention of the case.

“The promise of equal justice before the law required that this trial, like all criminal trials, be conducted with care to ensure fairness to both the defence and the prosecution.”

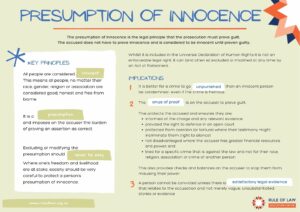

2. The presumption of innocence and the burden of proof

In every criminal trial, the key starting point is that the accused person is presumed innocent. The onus of proof lies solely with the prosecution. It is the State that has brought the charges and it is their responsibility to establish the requisite elements of the crime. As Justice Hall stated:

In every criminal trial, the key starting point is that the accused person is presumed innocent. The onus of proof lies solely with the prosecution. It is the State that has brought the charges and it is their responsibility to establish the requisite elements of the crime. As Justice Hall stated:

“an accused person does not have to prove his or her innocence, indeed he or she does not have to prove anything. The onus is on the State from start to finish. It never shifts to the accused”. [98]

The standard of proof that the Prosecution must meet in order to prove the accused guilty is beyond reasonable doubt. Beyond reasonable doubt is the highest standard known to the law. This high burden of proof reflects the important principle that an accused is entitled to the presumption of innocence. In the words of Justice Hall:

“The accused was presumed innocent, the State bore the onus of proof and the standard of proof was beyond reasonable doubt”. [5]

As His Honour stated:

“It is only if all elements are proven beyond reasonable doubt that the accused can be found guilty of a particular charge”.

His Honour found the accused not guilty of Ms Spiers’ murder, even though His Honour concluded the accused was guilty of the other two murders. It was the Prosecution’s submission that the similarities between Ms Spiers death and the other two murders which the accused was guilty of proved beyond reasonable doubt that he was responsible for Ms Spier’s murder, but His Honour disagreed. Although the propensity evidence would suggest the accused was responsible, “

A possibility or even a probability in that regard is not enough to support a conclusion beyond reasonable doubt”. [24]

His Honour’s judgement reinforces just how high the threshold of “beyond reasonable doubt” actually is and confirms that in circumstance where the threshold is not satisfied, the accused must be found not guilty.

3. The judicial system is independent, impartial, open and transparent and

provides a fair and prompt trial.

In a country that upholds the rule of law such as Australia, it is essential that the judicial system remains independent, impartial, open and transparent. In a Judge alone trial such as in this case, the presiding judge is required by law to ensure their judgement includes the principles of law that the judge has applied and the findings of fact which the judge has relied upon. The judgement must reveal a process of reasoning which makes clear how the conclusions have been reached. The judgement is made publicly available and is open to scrutiny from the public. These judicial conventions ensure the judicial officer can justify their reasoning, can be held accountable and open to scrutiny through an established process of appeal.

Regarding open justice, His Honour in his judgement reflected on this critical concept:

“Access by the media is an important part of ensuring justice is not only done but seen to be done. Whilst the court was open to the public, the media played an important role in ensuring that those who were unable to attend could remain informed as to the progress of the trial.” [ 106]

4.The Right to Silence

In Australia, an accused person has a right to silence from the moment they are arrested right through until the conclusion of the trial against them. An accused person is not obliged to speak to the police or to give evidence at their trial, but they may do so if they wish. In this case, Mr Edwards exercised his right to silence during the trial and did not give evidence.

The right to silence is critical and strengthens the onus of proof: that, is the State’s responsibility to prove the case beyond reasonable doubt. Moreover, the accused person’s exercise of the right to silence cannot be used as evidence against them, nor can it be used to support any inference adverse to them.