Skaf Case Note

For crimes that society considers as the worst of crimes, should the accused be expected to serve a life imprisonment? Should the criminal process be applied differently to the perpetrators of crime that society considers the most heinous of human behaviour? What happens when a criminal’s sentence has been served and the accused remains unrepentant? This case note examines the case of the Skaf brothers and it’s relevance to the consideration of aggravating and mitigating factors in sentencing, the principles of totality and proportionality, parole and how jury misconduct can impact on fairness.

Content Warning: The following case note involves a sexual assault case. It does not detail any specifics of the offence but considers sentencing, juries and parole. Readers are advised to view content before proceeding.

The Skaf cases fall into the category of what society considers the most horrific of crimes. However, no matter the crime, the rule of law must prevail.

The rule of law underpins the criminal investigative process, the criminal trial process and sentencing. In criminal cases such as the Skaf Case, the principles surrounding the rule of law must be followed regardless of the severity of the crime and must be calm and measured and include:

·  affording the accused presumption of innocence ,

affording the accused presumption of innocence ,

· a fair and prompt trial process, and

· applying the law equally and fairly

No one must ever be considered above or beneath processes of the law

This case note presents information on sentencing, the role of the jury, and parole.

Download PDF of Skaf Case Note

Click on the below images to go to each section.

Case Summary

Brothers Bilal and Mohammed Skaf lead several gang rapes on young women across Sydney in the early 2000s.

Mohammed Skaf’s recent release on parole 6 October 2021, after serving 22 years in prison, has reignited a media debate about the adequacy of criminal sentencing and whether perpetrators of such crimes should be released on parole.

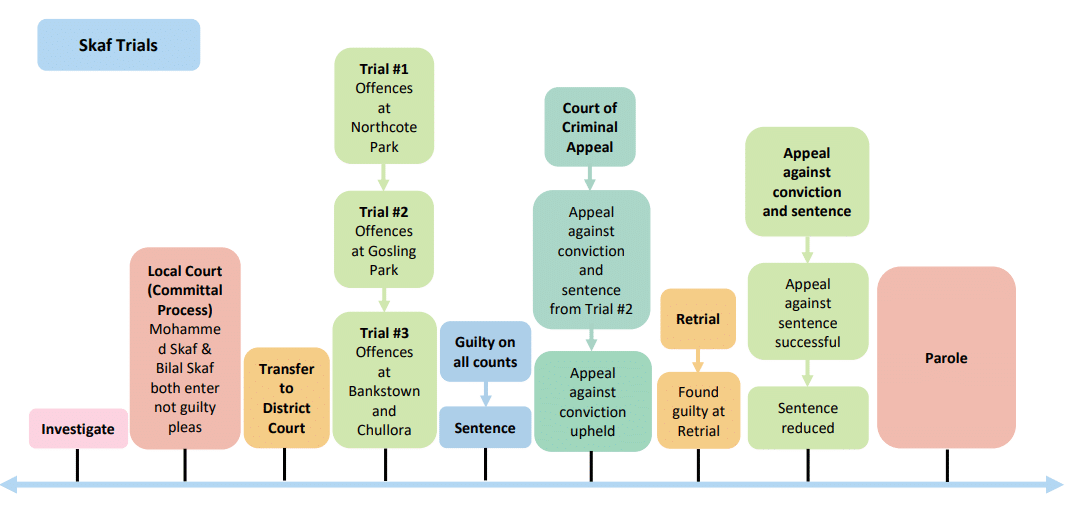

The Skaf brothers, along with several other men who also took part in the crimes, faced multiple consecutive trials.

Bilal Skaf faced three trials for the offences; with Mohammed Skaf co-accused for two of the trials. The trials were heard in the District Court of New South Wales before Judge Michael Finnane QC. In all three trials, the jury found the men guilty of each charge. Under the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW), Judge Finnane QC sentenced Mohammed to 32 years in prison for his involvement in the crimes. Bilal Skaf was sentenced to 55 years with a non-parole period of 40 years.

At the time, this was the longest non-life sentence ever handed down in Australia.

Both Mohammed and Bilal Skaf were successful in their appeals against the length of their sentences arguing that they were manifestly excessive. The NSW Court of Criminal Appeal reduced their sentences several times. The appeal relating to the second set of offences at Gosling Park in Greenacre succeeded because the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal found the jury’s misconduct led to a mistrial, the court ordered a retrial as a result.

Bilal Skaf is now serving a 31-year sentence with a minimum of 28 years. Mohammed Skaf’s original sentence was reduced on appeal to 23 years with a non-parole period of 18 years.

Mohammed Skaf was released from prison in October 2021.

Sentencing: For the most horrific of crimes, what is a just and proportionate sentence?

Sentencing: For the most horrific of crimes, what is a just and proportionate sentence?

Bilal Skaf appealed the sentences that were imposed by Judge Finnane QC to the Court of Criminal Appeal (CCA). The CCA allowed his appeal and quashed the sentences imposed by Judge Finnane QC. The court deemed the original sentences handed down by Judge Finnane QC infringed the principle of totality.

The principle of totality: a principle of sentencing to assist courts when sentencing an offender for a number of offences that ensures the sentence reflects the overall criminality of the offending behaviour. The sentence must be just and appropriate to the totality of the behaviour.

Since the Skaf brothers were sentenced for multiple offences, the court must ensure the aggregate or overall sentence is “just and appropriate” to the totality of the offending behaviour.

Whilst the CCA agreed that the offences committed were extremely serious, the court “could not categorise them as being within the worst category” when considering the scale for the severity of that crime. Bilal was resentenced to 28 years in prison for the two sets of offences.

Following the jury misconduct, the Skaf brothers faced a retrial where they were found guilty and resentenced by Acting Justice Matthews. The sentence imposed by Matthews JA extended Bilal’s overall sentence to 38 years and extended Mohammed Skaf sentence to 26 years.

The brothers appealed the sentence imposed by Matthews JA. The appeal was heard before McClellan at CL, Hidden J and Howie J in the CCA. The lawyers for the Skaf brothers advanced several reasons for why their sentences should be reduced, including the amount of publicity surrounding the first trial, in conjunction with the other trials, as well as the timing of trials in combination with a focus on radical elements of the Muslim community following the September 11, 2001 attacks.

The appeal against their conviction was rejected but leave to appeal against their sentence was granted. The court considered Bilal’s status as a high-risk inmate remanded in protective custody, and the limits and restrictions this imposes upon his access to education, work, and exercise whilst in prison. The sentences imposed by Matthews AJ were quashed on appeal because the CCA determined Her Honour’s sentence had not given adequate weight to the principle of totality.

Bilal’s total sentence will therefore expire on 11 February 2037, and he will be eligible for release on parole on 11 February 2031. The effect of this resentencing reduced the overall sentence and the non-parole period each by 2 years.

How was the sentence determined?

In determining the appropriate sentence, the Judge must consider what the law says. The Crimes Sentencing Procedure Act 1999 outlines what a Judge must consider when determining the sentence for an offender.

Firstly, they must look at the objective seriousness of the offence/s. The Judge will also consider whether there are any aggravating factors. Aggravating factors refer to things that make the offence more serious such as the offence being committed with other people, if the offence was violent in nature or part of a planned, organised criminal activity, and the substantial emotional harm caused by the offence upon victims.

A Judge must also consider the mitigating factors; these are the factors that reduce the seriousness of the offence. This includes if the offender is unlikely to re-offend or the offender has shown remorse. The Judge will also consider subjective factors; these are things specific to the offender. In criminal law, those who enter into a guilty plea at the earliest opportunity are also entitled to a reduction of their sentence

After a Judge has taken these factors into account, they apply a process called ‘instinctive synthesis’ to arrive at what they deem an appropriate sentence. An offender can appeal their sentence if they can establish that it is manifestly excessive, or the Judge applied the law incorrectly.

In Australia, a country governed by the rule of law, the sentence imposed must be just and appropriate in the light of the overall offending behaviour: the principle of totality. A just and fair sentence does not mean everyone will agree with it. A just and fair sentence is a sentence imposed according to the law and in line with the purposes of sentencing

For Mohammed Skaf, this included taking into account his youth at the time of offending and the fact that both Mohammed and Bilal Skaf’s cases pleaded not guilty to the offences.

The Skaf cases demonstrate the principle of proportionality. That is, the overall punishment is proportionate to the gravity of the offence. In the Skaf cases, Bilal Skaf’s sentence was greater than his brother Mohammed’s because it reflected that his offences were objectively more serious and had greater gravity.

Parole: For the most horrific of crimes, why are offenders released on parole?

![]() Before offenders are released on parole, they must have served the non-parole period of their sentence and the State Parole Authority (SPA) must determine an offender’s eligibility for release. This involves a number of robust processes the SPA goes through to protect the community and ensure that the reintegration of an offender back into society is supervised. The SPA considers several factors such as the advice of expert bodies, having regard for community safety, and the offender’s change in behaviour, attitudes, and completion of adequate programs in remand.

Before offenders are released on parole, they must have served the non-parole period of their sentence and the State Parole Authority (SPA) must determine an offender’s eligibility for release. This involves a number of robust processes the SPA goes through to protect the community and ensure that the reintegration of an offender back into society is supervised. The SPA considers several factors such as the advice of expert bodies, having regard for community safety, and the offender’s change in behaviour, attitudes, and completion of adequate programs in remand.

The SPA has no function to alter or increase a sentence imposed by the Courts. This is because the SPA is an executive body, and under the rule of law there is a clear separation between the roles of the executive, legislature and judiciary.

Mohammed Skaf’s release on parole in October 2021 reignited the debate surrounding parole. Mohammed first became eligible for parole in 2018 but was unsuccessful three times before being granted parole in 2021.

The State Parole Authority rejected Mohammed’s previous applications. In 2017 and 2019 the State Parole Authority expressed concerns that,

“it appears that he blames the victim for his offence, has no victim empathy and refuses to take responsibility for his actions. This lack of remorse is one of the reasons he has been assessed as a medium to high risk of reoffending again in the next five years”.

The reasons Skaf was granted parole in October 2021 were outlined by the State Parole Authority chairman David Frearson SC,

“Parole for the final two years of his sentence was the safest pathway for his reintegration into society. This is the only opportunity to supervise a safe transition into the community in the small window of time that we have left”.

The Serious Offender Review Council recommended Mohammed Skaf be released on parole. Mohammed was released on parole subject to various strict parole conditions. These include:

- Mandatory 24-hour electronic monitoring with daily reporting schedules

- Compliance with ongoing psychological intervention

- A ban on any form of contact with his victims

- A ban on contact with any co-offenders

- Exclusion zone orders for the local government areas of Liverpool, Fairfield, Blacktown and Parramatta

Why is parole important for the offender and the community?

The release of Mohammed Skaf on parole has caused considerable backlash from the community. However, when considering the release of Skaf, we must consider whether his parole achieves justice. The offences committed by Mohammed are undoubtedly horrific offences, yet even when ‘the worst of the worst’ crimes are committed, it is important that we uphold the criminal processes that, in turn, uphold the rule of law. “The cases that society has found most heinous have always been those in which the rules of fair and just procedure have come under attack”, and this is applicable to this case.

Regardless of how society may view the seriousness of a crime and the appropriate punishment, our criminal justice system must be balanced. Fair and proper procedure and laws must be followed to achieve a balance and, subsequently, a just outcome. If an offender has met all the requirements to be eligible for parole and the SPA has deemed them eligible for release, then the offender should be released on parole regardless of the crimes they committed.

Margaret Cunneen SC, the former Deputy Crown Prosecutor who prosecuted the Skaf cases in the early 2000s, considers the parole of Mohammed indeed achieves justice, for:

“He is now 38…he has arguably learnt his lesson” and “done his time.”

As the SPA said,

“Skaf cannot be kept in prison beyond his sentence and his inevitable release must be supervised. Every determinate sentence imposed by a court comes to an end. Freeing Skaf at the end of his full 23-year sentence without extensive monitoring and conditions would pose an unacceptable risk. Usually, release is inevitable. It is important to provide structure to facilitate re-integration in the interests of community safety.”

Parole balances the rights of an individual and the concerns of the community, ultimately upholding the rule of law.

Law Reform: How did the Jury’s misconduct prevent a fair trial?

At the commencement of any criminal trial, the Judge provides instructions to the jury. Jury directions are instructions from the Judge, designed to help jurors understand the law and the issues that arise in the case, so they can use the evidence presented in the trial to reach a verdict.

![]() In the Skaf trial, Judge Finnane instructed the jury that you are “not to go and do your own research.”

In the Skaf trial, Judge Finnane instructed the jury that you are “not to go and do your own research.”

At the second Skaf trial, a key issue was whether the victim had correctly identified Bilal Skaf as the offender. Since the offence occurred at night, much of the evidence led at trial was about the visibility at the park. The adequacy of the lighting in the park became an important factor.

At the conclusion of the second trial, the jury found both men guilty. However, sometime after the verdict, a solicitor unconnected with the case received information that the night before the verdict, the foreman and another juror had visited the park where the offence occurred. They had inspected the lighting and conducted their own experiments to assess whether a person could be clearly recognised at night from certain distances.

The solicitor was under the impression that the jurors had considered the information obtained when they “went to the park” which was not evidence in the trial. The solicitor reported this to the court.

The foreman said that he only went to the park to “clarify something for my own mind. I felt I had a duty to the court to be right. I wanted to be sure my decision was not in any doubt before the verdict. I did not tell anyone else in the jury about this visit. The only juror who knew about the visit was the one who was with me.”

On appeal, Mohammed Skaf’s lawyer, Stephen Odgers SC, said the jurors’ experiments concerning the lighting and weather conditions at the park resulted in them gaining additional information that was not admissible evidence. The Court of Appeal found that the ‘park experiment’ could not be considered part of the jury’s deliberations and stated:

“The Court cannot be satisfied that the visit to the park has not affected the verdict and that the jury would have retuned the same verdict if the irregularity had not occurred. The juror treated what was seen and done at the park as information that he took into account in arriving at or confirming his conclusion that guilt had been established beyond reasonable doubt” [paras 274 – 276].

The Court needs to “weigh the possible prejudicial impact” of the information “upon the minds and deliberations of (at least) the two jurors …This is because the information obtained by them was not evidence in the trial or properly put to them by the Judge with the knowledge of all the parties. Also, the evidence was obtained in circumstances amounting to procedural unfairness (denial of natural justice) as the accused were unable to test the material in any way.

Application of the Rule of Law

The key concepts underpinning Australia’s rule of law is that the law should be applied to everyone equally and fairly, the presumption of innocence and the principle of open justice should always be upheld.

In a fair trial, there are laws and rules that govern the way a trial operates. For example, the rules of evidence ensure everyone who is charged with an offence, regardless of the offence, is subject to the same restrictions on what evidence can and cannot be used. Both the prosecution and the defence must have a fair opportunity to address all the material considered by the jury when reaching its verdict.

The presumption of innocence imposes on the prosecution the burden of proving the charge and guaranteeing that no guilt can be presumed until the charge has been proven. The prosecution must prove an accused’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

In open justice, the defendant and the public – are entitled to know the evidence being considered by the jury. All evidence must be presented to the court so it can be scrutinised or explained by the accused’s defence team.

In one of the Skaf cases, the jurors sought their own external information, rather than solely relying on the prosecution’s evidence, to reaffirm their view of Bilal Skaf’s guilt. This evidence was not able to be cross examined with questions such as ‘was the time of year, and the time of day, the same as when the offence occurred?’, or ‘have the lighting conditions changed at the park in the years since the offence occurred?’ The conduct of the jurors and their reliance on extraneous “evidence” that was not presented at the trial meant the Skaf brothers were not afforded a fair trial and the principle of open justice was infringed.

Under the rule of law, everyone is entitled to a fair trial regardless of the crime. As a result, the Court of Criminal Appeal ordered a retrial.

Law Reform: What happens when laws do not match societies expectations?

With the separation of powers, the role of Parliament is to make laws. The role of the courts is to interpret, not make law, and to apply and interpret Acts of Parliament in the resolution of controversies.

See Case note on the Kables case and how judicial power can only be exercised by the Courts.

![]() Law reform occurs when there is community concern about an issue or a recent case that highlights a deficiency with the law. It is Parliaments role (and not the Courts) to make or reform laws on behalf of those whom they represent to resolve any perceived community issues. As stated by Former High Court Justice Dyson Heydon AC QC:

Law reform occurs when there is community concern about an issue or a recent case that highlights a deficiency with the law. It is Parliaments role (and not the Courts) to make or reform laws on behalf of those whom they represent to resolve any perceived community issues. As stated by Former High Court Justice Dyson Heydon AC QC:

Our common law system consists in the applying to new combinations of circumstances those rules of

law which we derive from legal principles and judicial precedents; and for the sake of attaining

uniformity, consistency, and certainty, we must apply those rules, where they are not plainly

unreasonable and inconvenient, to all cases which arise; and we are not at liberty to reject them, and

to abandon all analogy to them, in those to which they have not yet been judicially applied, because we

think that the rules are not as convenient and reasonable as we ourselves could have devised.Radical legal change is best effected by professional politicians who have a lifetime’s experience of assessing the popular will.. who have all the resources of the executive and the legislature to assist, who can deal with mischiefs on a general and planned basis prospectively, not a sporadic and fortuitous basis retrospectively, and who can ensure that any changes made are consistent with overall public policy and public institutions

Legal Reform and Jury Misconduct

The Skaf case and the jury misconduct led to the introduction of the Jury Amendment Act 2004 which amended the Jury Act 1977 by prohibiting jurors from making inquiries for the purpose of obtaining information about the accused or issues in the trial, except in the proper exercise of juror functions. This also prohibits jurors from searching the internet or conducting experiments to test evidence. The legislative change provides for harsher penalties for jurors who conduct investigations during the trial. The offence is punishable by a maximum of 2 years imprisonment.

The Skaf case also altered the way jury directions were given. Directions now cover outside experiments and direct juries that this type of investigation is illegal. Here is a sample of the written directions given to the jury at the opening of a criminal trial: https://tinyurl.com/3ckkm3dp

As a result of the Skaf cases, other reforms were made:

- New category of crime known as Aggravated Sexual Assault in Company

- Limitation on cross examination by unrepresented accused in sexual assault crimes

- Community messaging for victims of sexual assault

Further Information

Prezi made in 2012 by Catriona Steele on the Bilal Skaf Case

Finnane, M ‘The rape trials Australia can’t forget’ Australian Financial Review, 2 March 2018

Pennington, K ‘Innocent Until Proven Guilty: The Origins of a Legal Maxim’ CUA Law Scholorship, 200