Keli Lane Case Note

The Keli Lane case has captured the attention of the Australian public for over a decade since questions first emerged regarding the disappearance of Keli Lane’s baby Tegan in 2005. This attention intensified when Lane was charged with Tegan’s murder and subsequently found guilty by a Jury in 2010.

Case Update: On 22 March 2024, Keli Lane failed in her bid for parole due to the “No body, no parole” laws where the victim’s body is not found, the Parole Authority is required to refuse parole to those offendors who do not satisfactorily co-operate to identify the location of the vitictim’s body.

Following the release of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) documentary: “EXPOSED: The Case of Keli Lane” in 2018, there has been renewed interest and attention drawn to Keli Lane’s case. EXPOSED raised questions and doubts about Lane’s guilt, the police investigation and whether she received a fair trial.

This case note provides a review of both the Trial and Court of Appeal judgments and will demonstrate that even in high profile cases that attract intense media scrutiny, the principles that underpin the rule of law remain essential to uphold.

The rule of law ensures the law is applied equally and fairly, so that no one is above the law.

Click here to learn more about the rule of law

This case note should be read together with: “Additional Resources – The Keli Lane Case ”.

Case Citations

Trial Judgement: R v Keli LANE [2011] NSWSC 289 (15 April 2011)

Court of Appeal Judgement : Lane v R [2013] NSWCCA 317 (13 December 2013)

Bail application: Keli LANE v Regina [2013] NSWSC 146 (1 March 2013)

Facts of the case

Keli Lane (‘Lane’) was convicted by a jury of one count of murder and three counts of false swearing (i.e. making false statements under oath) on 13 December 2010. It was the Crown’s case that on or about 14 September 1996, Keli Lane murdered her then two day old daughter Tegan Lane.

Tegan was born on 12 September 1996. Lane left the hospital two days later with Tegan and this is the last time Tegan was either seen or heard from. It was Lane’s argument that she left the hospital and gave the baby to Tegan’s father, Andrew Morris or Norris (Lane could not remember which).

Tegan’s disappearance was discovered years later when a social worker discovered that her birth had never been registered. This set off a chain reaction with Police commencing an investigation and a Coronial Inquest into Tegan’s disappearance. The investigation resulted in Lane being charged with Tegan’s murder. After a six-month jury trial, Lane was convicted and sentenced to 18 years imprisonment.

The Crown’s case was entirely circumstantial, as Tegan’s body was never found, raising questions about intent and what might have happened to Tegan.

The Crown submitted that Lane had multiple secret pregnancies in the 1990s, two ending in termination and two resulting in adoption. During the course of the police investigation into Tegan’s disappearance, Lane gave a number of different versions of what had happened when she left Auburn Hospital with Tegan on 14 September 1996. The Crown argued that there was a pattern of behaviour, that included keeping secrets, and that Lane lacked any credibility. The inconsistent statements concerning what happened to Tegan were considered lies by the Crown and their existence suggested that Lane had a guilty conscience. The Crown put to the Jury that Lane’s desire to keep the birth of Tegan a secret and keep her reputation intact was motive for the murder. The Crown also suggested that there was no viable alternative to the story, such that the only possible conclusion one could reach, according to the Crown, was that Lane murdered her baby.

Lane’s defence was that the Crown could not prove Tegan was dead, let alone the manner of her death. Furthermore, the Crown could not produce any evidence to indicate that Lane was in any way responsible for what happened to Tegan. Lane maintained that she gave Tegan to her natural father, however the father could not be found. Moreover, Lane’s defence lawyers argued the Crown was unable to prove any act was done by Lane that demonstrated intention to cause Tegan’s death or to do her serious bodily harm, notwithstanding that the Crown bore the onus of proof.

Procedural History

At first instance, the case was heard in the Supreme Court of New South Wales before Justice Whealy and a Jury. The trial commenced on 9 August 2010 and concluded on 13 December 2010. The Jury returned unanimous verdicts of guilty on each of the false swearing charges and a majority verdict of guilty for the charge of murder.

The rule of law operates as a safeguard from untrammelled discretionary power to preserve liberty for citizens by ensuring they can live free from the direct application of power.

Checks and balances are an essential component to prevent the abuse of power and foster accountability for any power exercised. Central to the system of checks and balances is the doctrine of the separation of powers.

A majority verdict is a verdict agreed to by 11 jurors where the jury consists of 12 persons.

In respect of the conviction for murder, His Honour Judge Whealy imposed a sentence of imprisonment for 18 years, with a non-parole period of 13 years and 5 months.

Lane appealed against her conviction of the murder charge to the Court of Criminal Appeal. She did not appeal against the verdicts in respect of the false swearing charges.

Lane applied for bail pending the outcome of her Appeal. This application was refused on 28 February 2013, as Lane was not able to satisfy section 30AA of the Bail Act 1978 (NSW), which required Lane to establish that special or exceptional circumstances existed which would justify the grant of bail.

Lane’s appeal was heard before the Court of Criminal Appeal (Bathurst CJ, Simpson and Adamson JJ) on 23 July 2013. Their Honours dismissed her Appeal.

Lane returned to prison to serve the remainder of her sentence and will be eligible for parole on 12 May 2024.

Application of Rule of Law Principles

1. The Presumption of Innocence and the Burden of Proof

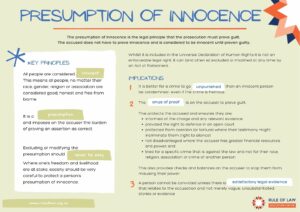

A key principle of the Australian criminal justice system is the presumption of innocence.

The presumption of innocence imposes on the prosecution the burden of proving the charge and guaranteeing that no guilt can be presumed until the charge has been proven.

The presumption of innocence only exists in the Australian legal system as a presumption in our common law. It can be excluded or modified at any time by a Federal or State Act of Parliament. Furthermore, Australia is a party to the international human rights treaty which ensures that all people, no matter their race, gender, religion or association are considered innocent unless proven otherwise. Article 14(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights guarantees the right to the presumption of innocence in relation to legal proceedings.

Under the presumption of innocence, the onus of proof is always on the accuser to prove guilt. This protects an accused and ensures that they are afforded certain rights. These include being informed of the charge and the evidence against them. They are provided the right to defence in an open court.

They have the right to silence and protection against self-incrimination. They are not disadvantaged where the accuser has greater financial resources and power. The importance and significance of the presumption of innocence is highlighted by the view that it is better for a crime to go unpunished than an innocent person be condemned. For this reason, the burden of proof in criminal trials is significantly higher than in civil matters because of the potential for a finding of guilty to result in the complete deprivation of ones freedom in the form of a sentence or imprisonment.

Click on the below images to learn more about the Presumption of Innocence

In criminal trials, the burden of proof lies with the prosecution (the Crown) to prove an accused person is guilty and the standard to which that proof is required is beyond reasonable doubt. This higher standard of proof in criminal trials guarantees that no guilt can be presumed until the charge against the accused has been proven. If reasonable doubt remains, the accused must be acquitted.

Under current Australian law – guided by the High Court’s decision in Green v R (1971) 126 CLR 28 – Judges are not supposed to give juries any clarification of what is considered to be “beyond reasonable doubt”.

The phrase beyond reasonable doubt is not to be explained beyond the ordinary meaning of the words and the High Court has said that “a reasonable doubt is a doubt which the particular jury entertain in the circumstances.”

For further reading in this area, click here: Beyond Reasonable Doubt

One of the major issues that the Lane case raises is whether, given that the Crown’s case was entirely circumstantial, the Crown met its responsibility to prove beyond reasonable doubt that Lane murdered baby Tegan.

In providing directions to the jury with respect to the charges Lane faced, His Honour Judge Whealy explained to the jury that the role of the Crown prosecutor is to prove the requisite elements of murder (such as mens rea (guilty mind), actus reus (guilty act) etc). If the jury was satisfied that the Crown had proven the requisites elements of murder beyond reasonable doubt, then it would be open to the jury to return a verdict of guilty. Alternatively, if the jury had any reasonable doubt in their mind about whether the requisite elements of murder had been established, then it would have to find Lane not guilty and acquit her of the murder of Tegan.

2. The Role of the Jury and the Judge.

In a criminal jury trial, it is important to remember the separate and distinct roles that the Judge and the Jury play. The High Court case of Alford v Magee [1952] outlines the duty of a judge in jury trials.

Jury:

- To solely decide on questions of fact

- To listen to all the evidence presented

- To make a determination based on that evidence as to whether the prosecution has proved the elements of the charge/s beyond reasonable doubt

Judge:

- To explain to the jury the relevant law (without excursions into interesting but inapplicable legal principles);

- To place that explanation in the context of the facts of the case;

- To explain how the law applies to the facts of the particular case;

- To give these explanations in the context of the issues in the particular case; and

- To identify the issues in the case as they have been fought between the parties.

Much has been made of the Trial Judge’s remarks following Lane’s conviction. Justice Whealy, who presided over Lane’s Trial, has spoken publicly about his unease at the outcome of the case. Those who criticise Lane’s trial frequently cite the remarks made by Justice Whealy in saying that he was unsatisfied with the jury’s verdict and felt the prosecution case was not proved beyond reasonable doubt.

However, it is important to remember that in the Australian legal system, the personal opinions of the judge are irrelevant and they are obliged to remain impartial when presiding over a case.

Learn more at – The Role of Juries

3. The Right to Silence

Lane chose not to give evidence during her trial. This is commonly referred to as the right to silence.

The right to silence is a fundamental legal principle tied to the presumption of innocence and ensures that no person is required to incriminate themselves.

There is no requirement that the accused give evidence at a trial. It is up to the prosecution to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the accused committed each element of an offence. An accused person is entitled to remain silent from the time of arrest when they are cautioned by the police until the conclusion of their trial.

Section 89 of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) states that if a party to a criminal proceeding refuses to give evidence, answer questions or respond to representations, an unfavourable inference must not be drawn.

It is important to note that since Lane’s trial, the law around the right to silence has changed.

In 2013, the NSW Government amended the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) by introducing a new section, Section 89A. This section states that in a criminal proceeding for a serious indictable offence, an unfavourable inference may be drawn from an accused’s silence in certain circumstances. Specifically, if the defendant fails to mention a fact that they later seek to rely on as their defence and in the circumstances, they could have been expected to mention this fact.

Under this new legislation, when someone is arrested the police caution states: “You are not obliged to say or do anything unless you wish to do so. But it may harm your defence if you do not mention something when questioned that you later seek to rely on in court”. This means that when questioned by police, if an accused person fails to mention an alibi or another relevant fact but then seeks to raise the fact at trial and rely on it as evidence of innocence, the Judge may allow the jury to draw an “unfavourable inference”, especially if the accused could reasonably have been expected to disclose a fact at the time and is seeking to rely on this face as a defence. Depending on the nature of the undisclosed fact this may, or may not, undermine the defence case.

Learn more at – The Fact Sheet on the Right to Silence

4. Right to Appeal

In Australia, a key component of the legal system is the right to appeal.

A person can appeal a judge’s decision to a higher court but can only do so on either:

- the grounds of an error of law,

- an error of fact, or

- an error of mixed fact and law.

Lane appealed her case, which was heard by the New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal. This is the highest court in State of New South Wales for criminal matters, with only the High Court sitting above it. The Court of Criminal Appeal typically sits with three judges, although five judges may sit when significant legal issues need to be considered. Each judge can make their own decision, or they can combine to write a joint judgement.

Lane appealed against her conviction on the charge of murder, raising initially eight grounds of appeal. Listed below are the eight grounds of appeal that were pleaded, together with our discussion on some of those grounds.

The 8 grounds of appeal:

The Trial Judge erred in failing to leave the alternative count of manslaughter to the jury.

1. The Trial Judge erred in failing to leave the alternative count of manslaughter to the jury.

2. The trial miscarried by reason of the prejudice occasioned by the Crown Prosecutor. In particular that he reversed the onus of proof in his closing address by positing a series of questions that he stated the defence had to answer.

3. A separate trial application should have been made by Trial Counsel in respect to the perjury/false swearing charges.

4. The Trial Judge should have directed the Jury that the charge of Infanticide was an alternative.

5. The trial miscarried by the failure of the Trial Judge to discharge the Jury after the Crown Prosecutor made prejudicial remarks in his opening address.

6. The Trial Judge erred in granting an application pursuant to Section 38 of the Evidence Act 1995 made by the Crown Prosecutor to have Mr Peter Jerry Clark cross examined due to him making an allegedly inconsistent statement.

7. The verdict is unreasonable and cannot be supported by the evidence

8. Failure of the Trial Counsel to ask for a direction that The Applicant had suffered prejudice as a result of the delay in prosecution.

During the course of the hearing of the appeal, ground 4 was abandoned.

Analysis of Grounds of Appeal

Note that numbers in [ ] refer to the paragraph numbers in the Court of Appeal Judgement.

Ground 1: The Trial Judge erred in failing to leave the alternative count of manslaughter to the jury

The Court dismissed the first ground of appeal based on the argument that the alternative count of manslaughter was never put to the jury, not because it was an error of the judge, but because it was a strategic decision by Lane’s defence team.

The Court of Appeal stated:

“A person accused of murder may perceive an advantage in casting upon the jury the responsibility of determining whether he or she is guilty of murder, or is to be acquitted, with no middle course available.”

Much of the Crown’s case focused on Lane’s state of mind and what inference could be drawn. The thing that could ultimately distinguish Lane’s guilt of murder from guilt of manslaughter was her state of mind. In contrast, Lane’s defence pointed to the fact that the Crown could not prove that Tegan was dead, nor did it have any evidence to establish that if Tegan had died, Lane was responsible.

The fact that no cause of death could be established played a very significant role in this case. In summary, there was insufficient evidence to justify a conviction of manslaughter, either by unlawful and dangerous act or criminal negligence. [See 104 – 105].

Their Honours Bathurst CJ, Simpson and Adamson JJ opined [at 107] that it is not the role of the jury to engage in speculation or conjecture. Rather, there must be an evidentiary foundation for a finding of manslaughter. They also observed that the jury heard a great deal of evidence regarding Lane, who was determined not to accept responsibility for the care of a child. At 111, their Honours accepted the jury were entitled to take into account evidence Lane gave concerning her disposal of Tegan to, as she asserted, the child’s natural father.

The jury were also entitled to accept the Crown contention that these were lies evidencing consciousness of guilt. These conclusions were in the Court of Appeal’s view sufficient to provide the evidentiary foundation for an inference that, in causing the death of the child, Lane had acted with the intention of killing and therefore, had the requisite mens rea (guilty mind) required for Murder. Accordingly, the judges rejected this ground of appeal.

Ground 2: The trial miscarried by reason of the prejudice occasioned by the Crown Prosecutor.

In particular that he reversed the onus of proof in his closing address by positing a series of questions that he stated the defence had to answer.

This second ground of appeal (above) was also rejected. In dismissing Lane’s claim that the Crown Prosecutor had reversed the onus of proof or alternatively, failed to establish her guilt beyond reasonable doubt, the Court of Criminal Appeal noted the Trial Judge in summing up the case to the Jury gave the following direction:

“I think you should be careful to remember that [a series of questions asked by the Crown] do not impose some type of onus on the defence to answer [those questions]. The defence does not have an onus of proof. They are more matters for your consideration in the light of all the evidence. The point I am making is that the Crown does not, by asking the question, alter or change the onus of proof which remains always on the Crown”.

The direction provided by the trial judge is significant as it emphasises that it is the Crown Prosecutor’s role to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused committed the offence. The Court of Criminal Appeal’s view was that it was inappropriate for the Crown Prosecutor to pose questions in summing up their case but after the above direction was given, the jury was not under any misapprehension as to who bore the onus of proof.

See the Pell Case Note for an example of a case in which the High Court opined the Prosecution did reverse the onus of proof.

Ground 7: The verdict is unreasonable and cannot be supported by the evidence

The role of the appeal court in considering a ground that a conviction is unreasonable and cannot be supported by the evidence is that the court asks itself the question: “whether it thinks upon the whole of the evidence it was open to the jury to be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt the accused was guilty”. M v The Queen [1994] HCA 63; 181 CLR 487, MFA v The Queen [2002] HCA 53; 213 CLR 606 and SKA v The Queen [2011] HCA 13; 243 CLR 400.

The Court of Appeal rejected Lane’s argument that the evidence to establish motive was weak. The Court of Appeal stated: “There was strong evidence that the appellant did not wish to accept responsibility for a child. In any event, it is not essential that the Crown establish a motive; evidence tending to establish motive was, in this case, one of many elements making up a circumstantial case”.

The Court of Appeal rejected this ground of appeal and stated [at 281-283]:

“The evidence, in our view, convincingly excluded any reasonable possibility … that the child had been given to her father. The police investigation virtually excluded any possibility that there existed a man named Andrew Morris/Andrew Norris with whom the appellant had “a brief affair”. Not one person with whom the appellant had been in contact at the relevant time came forward to say that he or she had known the appellant and Andrew Morris/Norris. The evidence strongly established that no such person had lived in the Wisbeach Street apartments that the appellant said that he had lived in. The police investigation pursued every line of inquiry left open by the appellant – his date of birth, his occupation (in finance), his participation in water polo. Leads given by the appellant proved false… Once the reasonable possibility that the appellant might have given the child to Andrew Morris/Norris is excluded, only one inference remains reasonably open. That is that Tegan is dead”.

In all of the circumstances, the Court of Appeal was satisfied that the verdict of guilty was amply open to the jury and that the evidence established beyond reasonable doubt the appellant’s guilt of the offence [see 291].

The judicial appeal process provides a powerful constraint on unbridled judicial power and is one of the express protections contained within the Australian Constitution. Clause 5 of the Constitution provides that all laws made under the Constitution will be binding on all Australian courts, judges and the general public.

The existence of a judicial appeal process and an ultimate court of appeal – namely, the High Court of Australia – ensure that Australian Courts and Judges can be held accountable. Appeals are the process by which judicial officers’ decisions can be reviewed. Appeals function both as a process for reviewing the appropriateness of a decision as well as for clarifying and interpreting the law.

The Keli Lane case continues to attract a great deal of public interest and Rule of Law Education will continue to monitor and report on developments in this case. The case is an illustration of important legal principles such as the presumption of innocence, the right to a fair trial and the rule of law.