Constitution Day: The ‘birth’ of Australia

Constitution Day is celebrated on 9 July each year.

This date is significant because it marks the date the Australian Constitution became law on 9 July 1900.

While July 9 is perhaps the least well-known date in the Australian calendar and is not accompanied by a public holiday, it is nevertheless a very important day for our nation.

Why is Constitution Day significant?

On this day in 1900, Her Majesty Queen Victoria signed the Royal Commission of Assent and in doing so, brought into existence the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (‘the Act’).

Constitution Day commemorates the date this law was passed by the British Parliament. Prior to that date, Australia existed as a collection of British colonies, which operated separately, yet ultimately adhered to the law making powers of the British Parliament. The new law brought together the states of New South Wales, Tasmania, Queensland, Victoria, Western Australia and South Australia under one federal government, which from then on was referred to as “The Parliament of the Commonwealth”.

The Act, the signed Royal Assent and the related documents which were responsible for the creation of our nation are sometimes affectionately referred to as Australia’s “birth certificates”.

Reasons for Federation

Before reading any further, it’s important to step back and take a moment to reflect on Australia’s history.

For over 50,000 years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples lived in Australia. From the late 1700s onwards, British colonies started to become established and by the late 1800s, six British colonies had been established, each with their own parliaments and each of which were subject to the law-making power of the British Parliament.

The six British colonies were like six separate countries and by the 1880s, there was a growing recognition that inefficiencies existed in many areas, including restrictions on transportation of people and goods across the continent. For example, each colony had its own laws, defence force, stamps and tariffs on goods that crossed its borders. These intercolonial barriers became increasingly unpopular with the collapse of the ‘land boom’ and resultant slowing of the economy in the early 1890s. Proponents for free trade argued that abolishing tariffs and creating a single market would strengthen the economy of each colony.

Immigration was also in the forefront of peoples’ minds. During the late 19th century, many colonists did not support immigration from non-British countries. It was felt that a national government would be better placed to control immigration.

In short, by the end of the 1800’s it had become apparent that the colonies faced issues of common concern which required some form of coordinated response.

‘The crimson thread of kinship’

The drafting of the Australian Constitution marked an attempt to draw together the people of six disparate British colonies and create one nation. The Constitution was drafted between 1891 and 1898, during a series of conventions attended by elected members of the six self-governing British colonies of Australia.

Sir Henry Parkes (b. 27 May 1815 – d. 27 April 1896), often referred to as the “Father of Federation”, was a significant colonial Australian political figure at the time. He was the longest non-consecutive Premier of the Colony of New South Wales, now of course referred to as the state of New South Wales. Parkes identified a growing sense of national pride, which he described as:

“the crimson thread of kinship that runs through us all”

– Henry Parkes.

Many colonial Australian politicians shared Sir Henry Parkes’ vision of establishing solid foundations for a national system of government, believing it could be achieved through reason and persuasion, without violence. His vision was to build a just, fair and egalitarian society through a democratically elected government. He also wanted all citizens to be aware of their rights and responsibilities and for them to have equal opportunities to participate.

On 24 October 1889, Sir Henry Parkes gave a rousing address at Tenterfield NSW, calling for a “great national government for all Australians”. The ‘Tenterfield Oration’, as it came to be known, sparked growing support for Federation.

Run up to the federation conventions

As with any subject, the historical and political context is important to understand and it is especially the case in this context, when we are trying to gain an understanding of the lead up to Australia becoming a Federation.

The following video provides a good overview of what Australia looked like prior to 1900 and how it came to become a nation: https://youtu.be/ecB-Lpm_AZ0

The following timeline is also a useful outline of key events towards Federation.

To quote academic Lisa Burton Crawford:

“By the late 1800s, the several colonies in Australia were practically self-governing. They had each acquired some sense of identity and they jealously guarded their interests – particularly interests of the economic kind”

– The Rule of Law and the Australian Constitution by Lisa Burton Crawford. Federation Press 2017.

In view of the dynamics between the various British colonies, it was not a guarantee that the colonies would agree to be amalgamated into one state. The challenge was to design a federal framework that the colonies would be agreeable to becoming a part of.

Below is a snapshot of some of the things that were going on in the six Australian colonies pre-Federation:

- Political parties had begun to emerge

- The Female Suffrage Movement had begun. South Australia and Western Australia had adopted voting for women in 1894 and 1899 respectively, whereas other states’ specific electoral laws did not give women the right to vote until Federation.

- Voting was not compulsory. It was initially limited to a select group of men who held property of a certain value. This was gradually expanded. Many eligible people did not vote and a considerable number of others were not eligible to vote. In the words of the Australian Electoral Commission: “Only South Australian and Western Australian women voted in the referendums. Indigenous Australians, Asians, Africans and Pacific Islanders were not allowed to vote in Queensland or Western Australia unless they owned property. In several colonies poor people in receipt of public assistance could not vote and Tasmania required certain property qualifications”.

- Until the 1850s, people voted publicly, which left them vulnerable to intimidation and coercion. To rectify this situation, the secret ballot was introduced.

- Racial conflict was in existence and was seen as a consequence of a multicultural society. It was felt that a national government would be better placed to control immigration.

The moment towards a federal system of government was eventually driven by pragmatism. Lisa Burton Crawford writes:

“Chief among these was the desire to alleviate the inconvenience and stultification of trade caused by intercolonial barriers, which discouraged the exchange of goods and services across the borders”.

The national ideal of Federation finally came into being on 9 July 1900 when, after a series of federation conventions, the Constitution was enacted. Representatives of the six colonies would meet at the so-called ‘constitutional conventions’ to draft legislation which would unite the colonies and the votes of 573,865 people in the six Australian colonies in the referenda of 1899 and 1900 would result in the ‘birth’ of Federation.

The above is only a very brief overview. In reality, the path to federation was much longer and sometimes rockier and the journey was stymied at several points.

A national ideal: the ‘birth’ of a nation

The 9th of July 1900 was a historically significant day for Australia. The Australian Constitution was the first national constitution in the world to be put to a popular vote.

The Commonwealth of Australia was established a year later, on 1 January 1901 and this is the day the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 came into effect.

Federation achieved the ‘birth’ of an independent Australia and this remarkable political achievement was marked by huge celebrations all across Australia.

Copies of the Act which established the Australian Constitution, the signed Royal Assent and the Letters Patent which established the office of the Governor-General of Australia have been preserved and are on display at the National Archives of Australia in Canberra. These documents are sometimes referred to as Australia’s “birth certificates”.

The Australian Constitution was a document that was considered very much ahead of its time. It became legislation during a period of great hope about the future and the possibilities of our nation. Australian lawyers Sir John Quick and Sir Robert Garran wrote in 1900:

“The new national institutions of Australia have to be tested in the fire of experience; provincial jealousies have to be obliterated; national sentiment has to be consolidated; the fields of national legislation and national administration have to be occupied. Australian statesmanship and patriotism, which have proved equal to the task of constructing the Constitution, and of creating a new nation within the Empire, are now face to face with the greater and more responsible task of welding into a harmonious whole the elements of national unity, and of guiding the Australian people to their destiny”.

Framework for a federal Commonwealth

The preamble to the Australian Constitution describes it as an Act to create “federal Commonwealth”, agreed to by “the people of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland, and Tasmania”.

The Constitution presupposes at several points the continued existence of the former colonial, now State Governments. For example, Section 77(iii) presupposes the existence of State Supreme Courts and Section 109 presupposes the existence of State laws and hence legislatures.

Section 92 of the Constitution ensures that trade within the Commonwealth shall be “absolutely free”. This section has been the subject of much debate in the High Court of Australia over the years. At this juncture, suffice it to say that when this section was first introduced into the Constitution, the way this section was envisaged to operate was as follows:

“I seek to define what seems to me to be an absolutely necessary condition of anything like perfect federation, that is, that Australia, as Australia, shall be free – free on the borders, free everywhere – in its trade and intercourse between its own people; that there shall be no impediment of any kind – that there shall be no barrier of any kind between one section of the Australian people and another; but, that the trade and the general communication of these people shall flow on from one end of the continent to the other, with no one to stay its progress or call it to account”.

– Sir Henry Parkes, Federation Conference in Melbourne, 1 Marcy 1890.

The drafters of the Constitution borrowed principles and practices from the United Kingdom and the United States. For example, the Constitution implements a system of representative and responsible government in the style of Westminster. There are numerous other sections that refer to or contemplate the involvement of the people in the political process. The drafters of the Constitution left much concerning the system of representative government to the discretion of the Parliament. The provisions establishing the system of responsible democracy are even fewer and far between.

Nevertheless, what is clear is that the drafters believed that this system of representative and responsible government would be sufficient to prevent the misuse or abuse of government power. Moreover, that the important questions concerning the nature and maintenance of the democratic order could be entrusted to democracy itself.

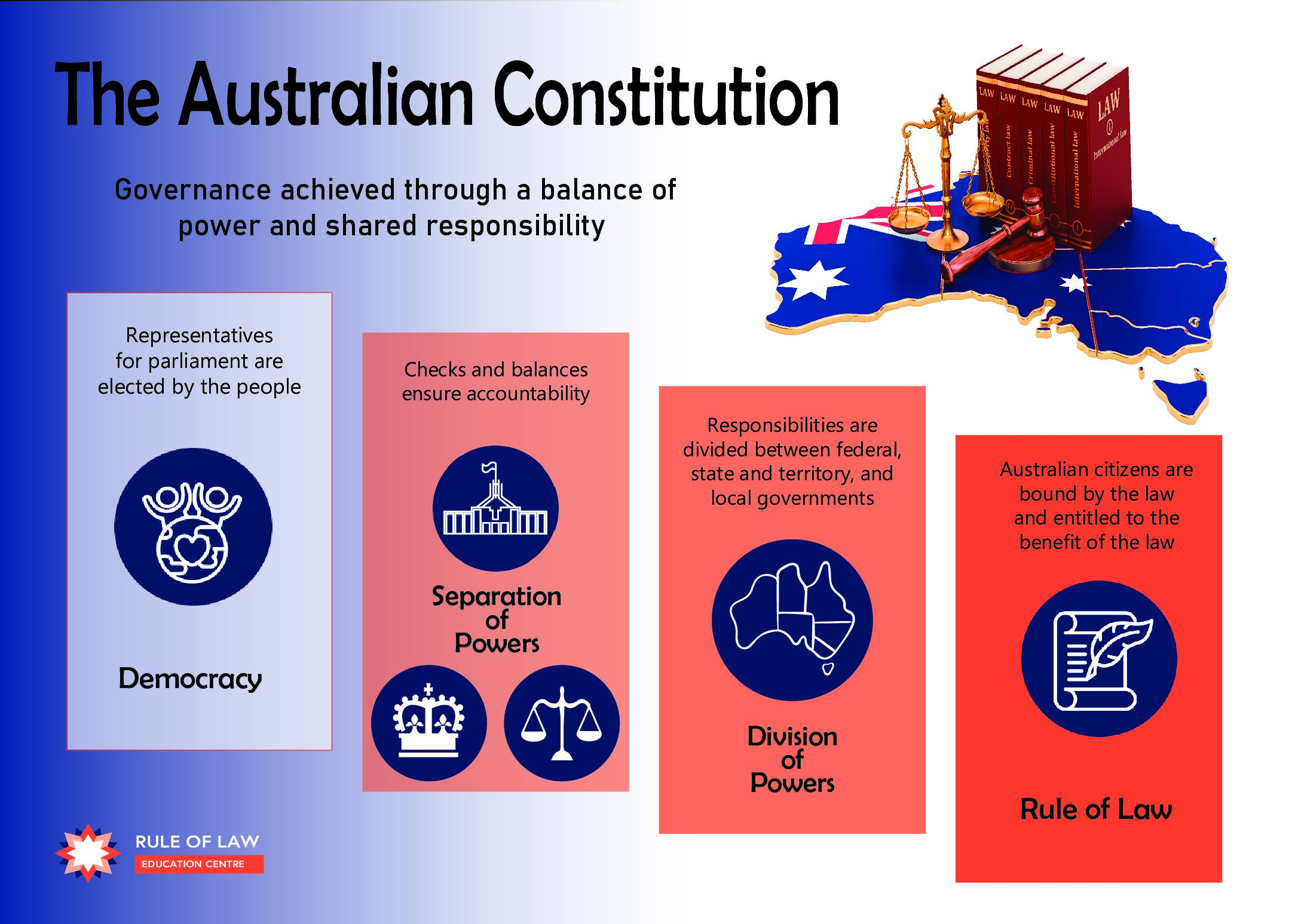

The Constitution imposes limits on legislative and executive powers, including limits on judicial independence. It is intended to bind all arms of the Commonwealth Government and to operate as Australia’s highest law.

Importantly, the Constitution was framed upon the assumption of the rule of law. That is, the law should be applied equally and fairly and that no one should be above the law.

Further reading about the Constitution click here.

Looking towards the future

Enhancing young people’s understanding of the history of our nation is key to our success moving forward.

Notwithstanding the historical developments that have occurred since Federation, it should be noted that the Constitution does not derive its binding legal force from common law principles, nor is it subordinate to them. On the contrary, all branches of the Federal Government continue to be legally bound by the Constitution.

By way of illustration, the Australian Constitution was designed to delineate the powers of the new Federal Government and it was always understood that those powers would be limited. While the Federal Parliament is the superior law-making body, its powers are expressly subject to the Constitution. Why? Because, as discussed earlier, all branches of government are bound by the Constitution.

This raises an interesting question. To what extent can the High Court enforce common law principles that are absent from the Constitution? The answer to this question is that there are constitutional instruments besides the Constitution that inform the scope of Australian governmental power but ultimately, the legislative power of the Commonwealth remains subject to the Constitution. So, while the High Court can have regard to extra-constitutional “norms”, it cannot alter the Constitution. In performing its functions, it must remain within the powers vested in it by Section 71 of the Constitution. It cannot exceed the limits of its judicial power.

Section 128 of the Constitution provides a means of amending the Constitution, but any proposed law to alter the Constitution must be passed by an absolute majority in both Houses of the Commonwealth Parliament.

To quote Sir Henry Parkes, the Constitution is the crimson thread of kinship that binds us all.

Constitution Day commemorates the journey the Australian colonies undertook to unite our continent and create one nation. In the words of Antonio Piccolo, SA Light MP:

“I see Constitution Day being a unifier of the Australian people, not just for those who were here at the turn of the century, but for all Australians, whether they came here 40,000 years ago, or more recently, and regardless of their country or origin.”

It is a blessing to live in an open, democratic, multicultural society in one of the most illustrious examples of mutual respect and understanding in the world. With pride in the things we have achieved as a nation over the last 120 years, we celebrate Constitution Day with the certainty that Australia will continue to learn from the past as it moves into the future.

The rule of law inspires and renews our commitment for greater accountability, greater justice and equal and fair application of the law for all Australian citizens.