Digital Justice

What We Can Learn from the Impact of COVID-19 on the Justice System?

COVID-19 and the unprecedented impact it had on the courts and justice system has provided a number of lessons and revealed opportunities for our justice system to continue to improve and evolve to ensure wider access to justice, and fair and prompt trials, are achieved. This resource will outline several advantages and disadvantages associated with incorporating technology into our justice system to enable legal processes to continue as normally as possible throughout the pandemic.

COVID-19 and the unprecedented impact it had on the courts and justice system has provided a number of lessons and revealed opportunities for our justice system to continue to improve and evolve to ensure wider access to justice, and fair and prompt trials, are achieved. This resource will outline several advantages and disadvantages associated with incorporating technology into our justice system to enable legal processes to continue as normally as possible throughout the pandemic.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic provided numerous challenges to various sectors of our society and forced us all to consider alternative ways of socialising and conducting business. Similarly, the justice system across Australia had to create new processes to ensure:

- Compliance with COVID-19 measures and

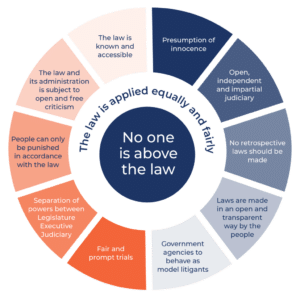

- Rule of law principles were upheld, such as fair and prompt trials and open justice.

A fair and prompt trial must ensure the prosecutor has the opportunity to prove his case and the defendant has the opportunity to rebut it. This is traditionally achieved via legal processes and procedures in a formal court setting. Open justice and transparency protects the rule of law and inspires confidence in the administration of justice by ensuring the public is informed about what is happening in the courts enabling scrutiny and accountability.

In response to COVID-19, a number of courts adapted their processes and mechanisms to incorporate digital means, such as conducting hearings via audio-visual (video) link (AVL) and using new databases whereby soft copy documents and evidence could be accessible to each party. This is what we refer to as ‘digital justice’: the use of technological measures to deliver justice.

At the very least, COVID-19 and the unprecedented impact it had on the courts and justice system has provided a number of lessons and revealed opportunities for our justice system to continue to improve and evolve to ensure wider access to justice, and fair and prompt trials, are achieved.

Advantages of digital justice

- Enables trials to be run during periods of lockdown and social distancing and capacity restrictions. This may help to reduce instances of delayed justice. “Justice delayed is justice denied.”

- Live streaming of high-profile cases can help Australians to gain a better understanding of the judicial system. It improves accessibility to trials for the public.

- Live streaming of cases increases transparency in court processes, in turn enhancing public confidence in the judiciary.

- Continual advancements of technology enable the courts to streamline processes.

- Younger participants may feel more comfortable engaging in technology-based processes, encouraging engagement.

- In some cases, access to justice may be increased through the use of technology. Those who may otherwise forego their right to find redress through the court system due to complications, such as distance, travel time and other expenses associated with going to court, can now seek justice from home using their own computer.

- Digital justice is more convenient for parties to a matter and lawyers, with higher participation and attendance rates reported.

- Digital proceedings may reduce the stress and anxiety associated with court attendance for some participants, particularly vulnerable people.

- Increases in urgent family matters during the Covid-19 pandemic, many arising from increased family violence during lockdowns and parental disputes over vaccinations, prompted the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia established the COVID-19 list. Dedicated to urgent family matters arising as a direct result of the pandemic, the eligibility criteria specify the matter must be able to be dealt with by electronic means, such as AVL, showing the courts willingness to adapt processes to achieve justice using technology.

Disadvantages of digital justice

- In a complex, formal and critical environment such as the courtroom, face-to-face communication is the most efficient and effective form of communication.

- A fair trial includes the right of the accused to physically face their accuser when accusations are being made.

- When considering the credibility of testimony, relevant inferences are often made according to the demeanour, body language, eye contact and the nature of responses given by the witness or offender. There are many forms of unconscious communication that occur in person that help individuals interpret the meaning behind words that are not apparent on technology, potentially complicating the ability of the court to understand testimony and impacting on trial fairness.

- Communication between the accused and their lawyer is more difficult in an online setting. Conversations and documents cannot be physically shared and engaged with subtlety, possibly requiring a recess each time conferral is needed.

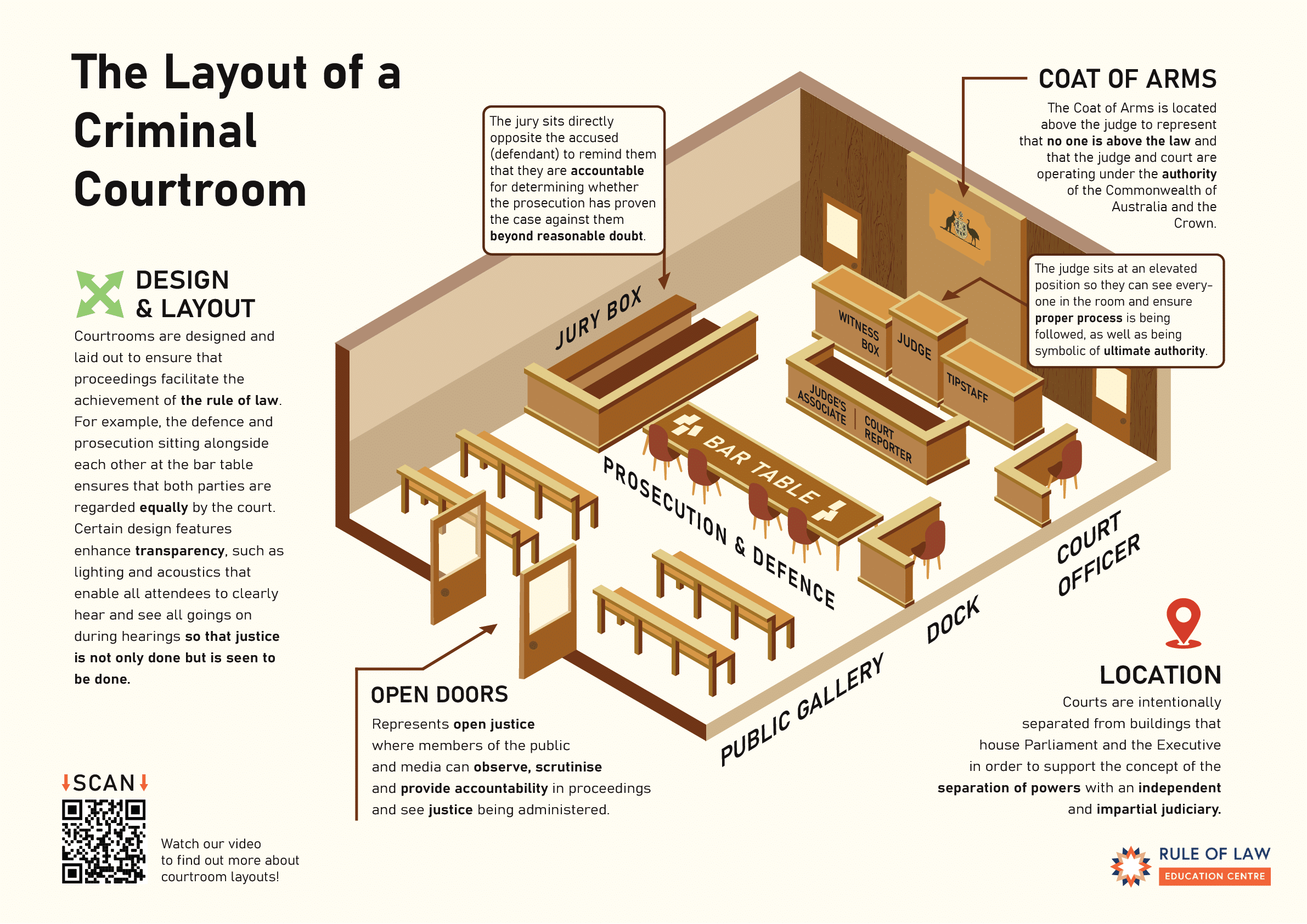

- Digital justice may diminish the formality of the justice system as participants cannot accurately gauge the tenor and solemnity of the courtroom. Courtroom layout has been developed over centuries to ensure the rule of law is upheld.

In a physical courtroom, participants must observe court etiquette and protocols to demonstrate respect for the court systems. This solemnity may be reduced during online proceedings as participants do not need to physically bow to the Coat of Arms when entering the courtroom or stand silently when a judicial officer leaves the room, being able to mute their audio.

Participants in digital justice do not physically sit in a courtroom which has the potential to reduce participants’ respect for the process of justice and reduce their engagement with procedures. - Digitisation of court proceedings may have limited access to justice for some people. The computer illiterate, elderly, disabled or vulnerable, those without access to technology or the internet, and those in regional areas with a non-stable internet connection all face barriers to justice in digitised court proceedings.

- There may be an increased burden on self-represented litigants who do not have the appropriate computer software and/ or the knowledge and ability to access court documents electronically.

- For criminal jury trials, court proceedings were suspended during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is because a virtual courtroom cannot prevent the problems of distraction and outside influence on jurors as a judge can do in a physical courtroom, potentially impacting on presumption of innocence and fairness.

- If trials are conducted remotely, it may be more difficult for individuals who require an interpreter to participate.

- Electronic storage of and access to sensitive documents and files must be subject to stringent cyber-security controls, possibly increasing costs in the justice system.

- With online cases, the ease of access to proceedings is impacted and the educative function of open justice is diminished. Members of the public cannot walk into a court room to view proceedings and in NSW, need to apply for an AVL for each specific case.

School and university students have been unable to physically visit the court, limiting deep understanding of and appreciation for court procedures designed to ensure equality and fairness for all before the law.

What can we Learn from this Experience?

With the above advantages and disadvantages in mind, below we consider what lessons we have learnt from the impact of COVID-19 on the court system, and if digital justice was to be implemented, what are some factors that should be taken into consideration.

Lesson 1

Where possible, cases should be held face-to-face in a built for purpose building to ensure a fair trial and open justice.

Lesson 2

Increased investment by the courts in advanced technology to ensure technical delays and difficulties are kept at a minimum.

Lesson 3

Continue to livestream proceedings to increase public confidence in the judiciary and court procedure.

Lesson 4

Online hearings could be integrated only out of necessity, for example, if it is impossible to ensure the physical presence of a person.

Lesson 5

Particular types of cases, such as civil disputes, could be conducted online since there is no jury requirement and parties could finalise their disputes more efficiently.

Lesson 7

To ensure that participants in court hearings understand the formality and context of the court, online hearings should ensure that the judge appears as they would in a courtroom: sitting raised at the front of the room underneath the coat of arms to symbolise themselves as an image of the judiciary.

Activites: Digital Justice in Action

Victoria

- Below is a link to the Victorian County Court website providing access to live virtual hearings.

https://www.countycourt.vic.gov.au/court-schedule/crime-and-appeals-list

- Similarly, the link below is to the Supreme Court of Victoria and allows views to live stream proceedings.

https://www.supremecourt.vic.gov.au/daily-hearing-list/live-streams

- Watch the sentencing of Rian Farrell in the Supreme Court of Victoria using the link below. (WARNING: the following link includes offensive language and concerns a fatality).

https://www.streaming.scvwebcast1.com/sentence-of-rian-farrell-tuesday-13th-july-2021-1130am/

Farrell pleaded guilty and was convicted on the manslaughter of his best friend after fatally stabbing him in the heart in 2020.

Consider:

- How is Justice Dixon positioned on the screen? Does her Honour appear as she would if you were watching in the physical courtroom?

- Throughout the sentencing, who can you see on screen? Do you think that you would be able to view witnesses, lawyers, and the accused if you were to watch the proceedings leading up to sentencing? Why would this be important?

Aitken, L., 2016. Interpreting R v Baden-Clay:’discovering the inward intention’, or ‘what lies under the veil’? University of Queensland Law Journal, The, 35(2), pp.301-311.