The lion’s den

The strange phenomenon of self-defeating defamation cases

Article by Professor Katy Barnett, Professor at Melbourne Law School

First Published on Substack, What Katy Did.

“Having escaped the lions’ den, Mr Lehrmann made the mistake of going back for his hat.”

– Lee J in Lehrmann v Network Ten Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 369 at [1091].

[Warning: discusses rape and sexual assault]

When I was a child, the only badge I received during my time as a Girl Guide was my Collector’s Badge, for inter alia, my date-ordered collection of fossils. Now that I am grown up, I collect other things: cases about failed gambling contracts, cases about animals, strange nuisance cases, and defamation cases where the plaintiff should never have gone to court, among other things.

One of my favourite examples of the latter is Grobbelaar v News Group Newspapers Ltd, (Note 1) in which the former Liverpool Football Club goalie sued in defamation after a newspaper published allegations of match-fixing (later found to be true). The House of Lords awarded him “contemptuous damages” of £1 (the lowest coin in the realm). Lord Bingham said:

The tort of defamation protects those whose reputations have been unlawfully injured. It affords little or no protection to those who have, or deserve to have, no reputation deserving of legal protection. Until 9 November 1994 when the newspaper published its first articles about him, the appellant’s public reputation was unblemished. But he had in fact acted in a way in which no decent or honest footballer would act and in a way which could, if not exposed and stamped on, undermine the integrity of a game which earns the loyalty and support of millions. Even if the newspaper had published no more than what, on my interpretation of the jury’s verdict, it was entitled to have published, the appellant would have been shown to have acted in a way which any right-thinking person would unequivocally condemn. It would be an affront to justice if a court of law were to award substantial damages to a man shown to have acted in such flagrant breach of his legal and moral obligations. (Note 2)

I have just been presented with a very fine specimen of an equally disastrous defamation case, Lehrmann v Network Ten Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 369, where the plaintiff sued to vindicate his reputation, but left the court with his reputation in tatters.

How the case arose

For non-Australian readers or Australian anchorites, the case involves two former political staffers, Brittney Higgins (Higgins) and Bruce Lehrmann (Lehrmann), who worked for a Federal Member of Parliament, Linda Reynolds (Reynolds), the then-Minister of Defence. On 22 March 2019, Higgins, Lehrmann and a group of other parliamentary employees went out for drinks. In the early hours of the morning, Higgins and Lehrmann went to Reynolds’ office. The question of what happened next has spawned what Lee J called an “omnishambles” of legal proceedings. (Note 3) On 23 March 2019, Higgins was found naked and still intoxicated on a couch in Reynolds’ office. She alleged that she had been sexually assaulted. In early April 2019, Higgins decided not to proceed with criminal allegations.

On 15 February 2021, journalist Samantha Maiden published an article entitled ‘Young staffer Brittney Higgins says she was raped at Parliament House’. On that evening, a broadcast was made on a television show called The Project by the host Lisa Wilkinson (‘Wilkinson’). Although the broadcast did not name Lehrmann, evidence was given to indicate that people who knew Lehrmann recognised him from the details that were given. Lehrmann said there were four defamatory imputations made in that broadcast:

- Lehrmann raped Higgins in Reynolds’ office in 2019.

- He continued to rape Higgins after she woke up mid-rape and was crying and telling him to stop at least half a dozen times.

- While raping Higgins, Lehrmann crushed his leg against her leg so forcefully as to cause a large bruise.

- After Lehrmann finished raping Higgins, he left her on a couch in a state of undress with her dress up around her waist.

Lehrmann has always denied that sexual intercourse took place.

Among other things, it was suggested in media reports that Reynolds’ office had tried to “cover up” the alleged sexual assault. This was found to be communicated to journalists by Higgins and her now-boyfriend, David Sharaz (‘Sharaz’). The judge found that there was no basis for this allegation. Higgins has since apologised to Reynolds and Fiona Brown (Brown), Reynolds’ former Chief of Staff, for hurt caused.

On 17 August 2021, Lehrmann was charged with one count of engaging in sexual intercourse with Ms Higgins without her consent, contrary to s 54(1) of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT). He was also publicly identified as the person who was the subject of the February broadcasts. The criminal trial was fixed for 27 June 2022, but was vacated because of pre-trial publicity concerning Higgins. A trial began on 4 October 2022. The jury retired for deliberations on 19 October 2022, but was discharged on 27 October 2022 for juror misconduct. On 2 December 2022, the then-Director of Public Prosecutions, Shane Drumgold, said that the prosecution would not continue because of the adverse effects on Higgins’ health.

Having avoided prosecution, Lehrmann then sought to sue various media outlets in defamation, including Ten Network Limited, the television station which broadcast The Project, and Wilkinson. In the defamation case, Lee J was sitting alone, and there was no jury. (Note 4)

There are numerous other legal cases associated with this dispute. (Note 5)

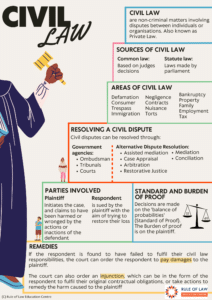

The tort of defamation

Defamation is a tort which occurs when someone publishes6 statements which adversely harm the reputation of another, and there is no basis for making those statements. Lehrmann’s allegation was that various news outlets had published statements about him which had adversely harmed his reputation. Lee J found that Lehrmann was defamed by the publications.

However, there is a defence to defamation; namely, it is not defamation if it turns out that the defamatory statements are true. Ultimately, the defendant was able to make out the truth defence. In other words, although the publication was indeed harmful to Lehrmann’s reputation, on the balance of probabilities, the judge found that the statements were true and therefore not wrongful.

Before further discussing the judgment, it is necessary to say something about how we prove things in court at common law. Much in this case turned on the evidence.

Civil and criminal proof

If a party seeks to prove something in court, they must meet the standard of proof. But the standard of proof varies according to the particular kind of case.

In a criminal trial, it must be proven that an alleged offender committed the crime beyond reasonable doubt. This means that there is no other reasonable explanation for what occurred, other than that the alleged offender committed the crime. As Lee J explains, our common law is based on the principle that it is better to let ten guilty people go than to imprison one innocent person. The consequences of criminal conviction are very serious. Hence courts make it difficult to establish guilt.

In a civil trial (i.e. not criminal), it must be proven that the defendant committed the act on the balance of probabilities. This is a lower standard of proof: the plaintiff simply has to show that it is more likely than not that the allegations occurred. Therefore it is easier to make out.

This explains the disparate outcomes in the famous OJ Simpson court cases. In the criminal trial, the prosecution was unable to prove beyond reasonable doubt that he had committed murder, but in a subsequent civil trial, the families of the deceased were able to prove on the balance of probabilities that Simpson had killed them.

Defamation is a civil cause of action, and consequently the burden of proof is the lower “on the balance of probabilities” standard. In assessing the truth defence, Lee J had to consider whether on the balance of probabilities, Lehrmann had done the things alleged in the publication. In a civil cause of action, the judge is also entitled to look at a wider range of evidence. Lee J concluded in the circumstances that, on the balance of probabilities, Lehrmann raped Higgins. His Honour conducted an exhaustive consideration of the evidence.

Who won? No one really “won”

At the outset Lee J noted that cause célèbre cases such as this one are always difficult to judge. As a result of the extensive media coverage, many people were highly partisan, and had already decided who they thought was in the wrong. He went on to say:

For some people, any unwelcome findings will be peremptorily dismissed. The reasoning process, including the drawing of fine distinctions based upon the subtleties of the evidence, will be of no interest. This reaction is inevitable given that several observers have a Rorschach test-like response to this controversy and fasten doggedly upon the “truth” as they perceive it. Their response is visceral because the “truth” is revealed and declaimed, rather than proven and explained. Some jump to predetermined conclusions because they are disposed to be sceptical about complaints of sexual assault and hold stereotyped beliefs about the expected behaviour of rape victims, described by social scientists as “rape myths”; others say they “believe all women”, surrendering their critical faculties by embracing and acting upon a slogan arising out of the #MeToo movement. Some have predetermined views as to the existence or otherwise of a conspiracy to suppress a rape for political purposes. For more than a few, this dispute has become a proxy for broader cultural and political conflicts. (Note 7)

Despite Lee J’s words of warning, it has been possible to discern precisely the phenomenon of which his Honour warned—people see what they want to see in the decision.

Actually, in my view, no one won. Lehrmann lost to the greatest extent, but almost no one emerged from the case with their reputation unscathed, other than Reynolds’ former Chief of Staff, Brown, who was said to have covered up a sexual assault in the 2021 media reports, when the very opposite was the case.

The difficulty with sexual assault trials is that, usually, because of the intimate and private nature of the offence, it is one person’s word against the other’s. This makes it particularly difficult to determine what happened. Moreover, the human memory is fallible, particularly in the wake of traumatic events such as sexual assault. I’ve had to consider whether I should bring charges against someone for sexual assault. I decided not to do so, in part because of the stress and difficulties of proof: my word against the other person’s. As Lee J notes, trauma can do strange things to your memory.8 This is something I know well on a personal level; I have gaps in my memory from that period of my life. Lee J is also acutely aware of the fallibility of human memory, as he acknowledges at [9] of his judgment.(Note 9)

It was particularly difficult in this case, as it transpires that both Lehrmann and Higgins were very poor witnesses, and the facts had long been caught up in the fog of politics.

An astute observer would have gleaned from the trial that this case is not as straightforward as some commentary might suggest. In part, this is because the primary defence hinges on the truth of an allegation of sexual assault behind closed doors. Only one man and one woman know the truth with certitude.

For an impartial outsider seeking to divine the truth (or, more accurately, ascertaining what most likely happened), two connected obstacles emerged.

The first is, at bottom, this is a credit case involving two people who are both, in different ways, unreliable historians.

…

To remark that Mr Lehrmann was a poor witness is an exercise in understatement. As I will explain, his attachment to the truth was a tenuous one, informed not by faithfulness to his affirmation but by fashioning his responses in what he perceived to be his forensic interests. Ms Brittany Higgins, Mr Lehrmann’s accuser, was also an unsatisfactory witness who made some allegations that made her a heroine to one group of partisans, but when examined forensically, have undermined her general credibility to a disinterested fact-finder.

The second and related obstacle was the assertion that what went on between these two young and relatively immature staffers led to much more. By early 2021, allegations of wrongdoing had burgeoned far beyond sexual assault. It was said a sexual assault victim had been forced by malefactors to choose between her career and justice. The perceived need to expose misconduct (and the institutional factors that allowed it) meant the rape allegation was not pursued in the orthodox way through the criminal justice system, which provides for complainant anonymity.

As we will also see, when examined properly and without partiality, the cover-up allegation was objectively short on facts, but long on speculation and internal inconsistencies – trying to particularise it during the evidence was like trying to grab a column of smoke. But despite its logical and evidentiary flaws, Ms Higgins’ boyfriend selected and contacted two journalists and then Ms Higgins advanced her account to them, and through them, to others. From the first moment, the cover-up component was promoted and recognised as the most important part of the narrative. The various controversies traceable to its publication resulted in the legal challenge of determining what happened late one night in 2019 becoming much more difficult than would otherwise have been the case. (Note 10)

How could the judge find that rape occurred?

I’ve had many people ask me how the judge could find that rape occurred. As this was a civil trial, there was a greater range of evidence available, and, as I’ve noted above, the standard of proof was lower. Moreover, various parties were forced to “discover” the material they had relating to the matter, and provide it to the court.

Lee J undertook a meticulous forensic analysis of all contemporaneous evidence, and found that Lehrmann had been attracted to Higgins for some time before the incident of March 2019; that on the night of the incident, Lehrmann had bought Higgins a lot of alcohol (much more than he himself drank); that later Lehrmann and Higgins kissed passionately at a nightclub; and that they had gone back to Reynolds’ office not to work, but to continue their assignation (both had other partners at the time). Lehrmann’s explanation that he was working on Question Time matters for the Minister was given extremely short shrift by the judge.

The texts to friends in the days afterwards from Higgins (at least, those she had not deleted) indicated that she did not have a clear memory of what had occurred, given her level of inebriation, but that she recalled being sexually assaulted. She remarked in a text to one friend three days after, “I could not have consented. It would have been like f**king a log” and in a text to her ex-boyfriend, also shortly afterwards, “Yeah, it was just Bruce and I from what I recall. I was barely lucid. I really don’t feel like it was consensual at all.”

The judge simply had to find, on the balance of probabilities, that it was more likely than not that Lehrmann had raped Higgins. [Edited to remove findings the judge did not make] In light of all the evidence, and in light of Lehrmann’s lack of credibility on a whole range of matters where he had been proven to have misled the court, Lee J found that these things had occurred, more likely than not. If it’s one person’s word against another’s, the relative credibility of the two really matters. Neither alleged perpetrator nor alleged victim were entirely credible, but in the light of contemporaneous communications and all the circumstances, the alleged victim’s account of the incident was more credible.

It is worth, however, recalling Lee J’s warnings at [1092] – [1094] of the judgment.

As I stressed at the commencement of these reasons, there is a substantive difference between the criminal and civil standards of proof. To make the grave finding Mr Lehrmann raped Ms Higgins, it is unnecessary for me to reach a level of certainty indispensable to criminal liability. The respondents have not won because I can exclude all other possibilities as to what happened, but because they have proven that such possibilities that are open on the evidence, both individually and collectively, are unlikely; and further because I am satisfied that the evidence provides an appropriate basis upon which to reach a conclusion. Put another way, they have proven that the whole of the evidence, properly analysed, establishes a reasonable satisfaction on the preponderance of probabilities of facts sufficient to make out the substantial truth defence.

As a result of the inconclusive criminal trial, Mr Lehrmann remains a man who has not been convicted of any offence, but he has now been found, by the civil standard of proof, to have engaged in a great wrong. It follows Ms Higgins has been proven to be a victim of sexual assault.

At first glance this might be thought to be an odd outcome. But if one leaves aside superficial reactions and appreciates the high value the common law has always placed upon the importance of securing against the conviction of the innocent, it is not at all peculiar. Ensuring an accused is deprived of their liberty only if the prosecution can exclude all reasonable hypotheses consistent with innocence, has been as elemental to our criminal justice system as the presumption of innocence and the related “golden thread” running through the criminal law that the prosecution bears the burden of proof…

So, Lehrmann will remain free of any criminal conviction, but he has destroyed his own reputation. Even if an appeal is granted, he has been found to be a highly unreliable and untruthful witness.

I have never quite understood why someone would bring an action in these circumstances. I can only postulate that it is a form of self-deception: I am a good person—surely I would not do something like this—therefore I did not do this, and I must sue to vindicate my reputation. We all like to see our past actions in the best way possible, and we often reformulate our past actions in our heads to ensure that they fit with our mental vision of the person we’d like to be. I have seen witnesses behave like this before in court, and deny the relevance of evidence which directly conflicts with the story they now want to tell themselves about what occurred.

Heroic journalists? Hardly

However, Channel Ten and Wilkinson certainly did not get away scot free either. It was found that the publication of the defamatory imputations was not reasonable, and that they did not properly consider whether Higgins and Sharaz had other motives in bringing the story to them at that point, or interrogate inconsistencies in the accounts given by Higgins and Sharaz. Hence, at [1096], Lee J says

But even though the respondents have legally justified their imputation of rape, this does not mean their conduct was justified in any broader or colloquial sense. The contemporaneous documents and the broadcast itself demonstrate the allegation of rape was the minor theme, and the allegation of cover-up was the major motif.

Margaret Simons, in a helpful article, suggests that part of the problem here was advocacy journalism: journalists advocating for a particular cause. I’d go further and say the problem is activist journalism. As I’ve said elsewhere:

Activism, to me, is not simply advocating a point of view. It is adopting one side of a debate wholeheartedly, to the point of taking strong actions to support it.

The corollary to this, often, is that anything said which questions the activist account in any way, even a small way, is verboten, evil and ridiculous. Strong action must be taken against questions, and they must be shut down.

Advocacy is different. Advocacy involves arguing a particular point of view strongly. I believe advocacy is appropriate in an academic context, as long as the possibility of other credible points of view are acknowledged, and the reader is shown where those points of view can be found.

The same is true of journalism: one can advocate for a point of view, as long as one is even-handed and acknowledges credible alternative points of view. And, as part of being a professional journalist, it’s really important not to accept information uncritically if it supports one’s prejudices, and fail to consider any evidence to the contrary, as it seems Network Ten and Wilkinson did.

Conclusion

I suspect this is not the last we’ve seen of this matter, given the plethora of other cases which have spawned in the wake of the initial broadcasts. I really hope that it leads to some change in journalistic practices. I was really dismayed by the lack of critical thought displayed by the journalists involved in this matter.

Another dismaying aspect was that the case overturned a rock, disclosing the creepy-crawlies of the political culture of Canberra underneath. Are all Ministers’ offices staffed with young political tragics, desperate to “hook up”, party and drink, and later, make it as a politician? Are these the people who control our access to our democratic representatives, and decide what matters? If so, God help us all. They seem not to have any experience of a life outside the fervid world of politics and the “Canberra bubble”. Ideally, I would want political staffers (and politicians, for that matter) to have spent at least five years outside politics or political-type jobs. (Note 11)

Ultimately, the lions left almost everyone somewhat savaged, but that’s the way things go if you choose to jump into their den unwarily.

Notes

Resources from Rule of Law on Defamation and Civil Cases

- Defamation and Allegations of Murder and War Crimes

- Defamation and Social Media

- Defamation and 2021 Law Reform

- Defamation and Law Reform: Geoffrey Rush Case Note

- Defamation and Public Interest Defence