Guest post written by Dr. Binoy Kampmark who was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures in law and politics at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: bkampmark@gmail.com

It’s all the legislative rage at the moment in Queensland: attempts to target “Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs”. Three laws of concern have been passed, including the Vicious Lawless Association Disestablishment Bill 2013; the Criminal Law (Criminal Organisations Disruption) Amendment Bill 2013 and the Tattoo Parlours Bill 2013. Their purpose? To “severely punish members of criminal organizations that commit serious offences.” Queensland Attorney-General Jarrod Bleijie argues that the laws deal with “the worst of the worst”.

They were passed in haste – a response to a bikie brawl on the Gold Coast last month. They were passed with minimal consultation, an even more essential feature given the lack of an upper house in Queensland. They were passed in an atmosphere of drummed up emergency to target a “new” criminality deemed even more serious than the police corruption of the 1980s, a claim that has been challenged as ludicrous.

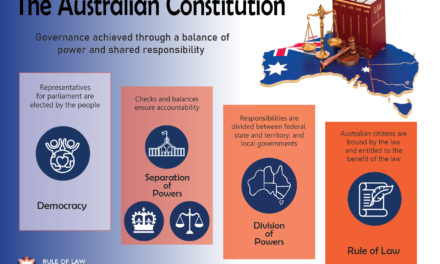

The laws have various serious effects, three of which have been identified by Kate Galloway. They target freedom of association, a collective punishment that focuses on “bikie” membership rather than criminal acts. Recreational riding risks falling under the umbrella. They make a pre-emptive strike at purported criminality, overturning the presumption of innocence – mere membership presumes criminality. The onus is on the accused to show non-membership of any such gangs. They also suggest a trend of targeting the separation of powers, or at the very least showing an ignorance of the convention.

There is little doubt that the legislation has worried the judiciary as sailing dangerously close to violating the separation of powers. The latest act in this legal drama involved Justice George Freyberg of the Queensland Supreme Court as he stayed an application for a review of a magistrate’s bikie bail decision.

Justice Freyberg argued that the comments by Premier Newman would allow any reasonable member of the community to infer that the courts would wish bail to be refused to Jarred Brown, the applicant in the proceedings. “Thereby the power of the executive arm of the government would be enhanced and the independence of the judicial arm damaged.” Such damage would affect “the institutional integrity of the court.” (Courier Mail, Oct 31, link)

The move was rebuked by the government, suggesting that the Newman government is not averse to attacking the judiciary, and, more broadly, the legal profession. In fact, it has become a core policy objective: law is best left to the police and the executive, not judges and lawyers who best be compliant in this new compact of governance. He has extolled lawyers in the state to “come out of your ivory towers” and bend to laws that were passed “because the system was failing” (Brisbane Times, Oct 24, link). In such towers, lawyers socialise, then “go home at night to their comfortable, well-appointed homes”.

There are also fundamental problems with targeting specific sections of the population with punitive laws that prescribe super prisons, special uniforms, and mandatory terms of punishment. In Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions for NSW [1996] HCA 24 , the High Court claimed that the Community Protection Act 1994 (NSW) was invalid in vesting non-judicial powers in the state court. The law would have allowed the court to warrant the continued detention of Gregory Kable as a threat to the public despite pending release. The principle has been applied unevenly, allowing state governments leg room to breach the separation of powers convention.

Attempting to keep judicial waters uncontaminated by executive fiat remains a vital feature of the rule of law. It is broadly accepted in Western jurisprudence, and embraced by the United Nations. To violate the convention is to add power to the dangers of demagogic rule. Justice Freyberg has admitted as much, for as political power “is notoriously the product public perceptions” a politician who is perceived to be effective will have an “enhanced” appeal. That appeal should not come at the expense of independent judicial process.