Case Note: Kristian White and Clare Nowland

Introduction

The conviction of Kristian White for the manslaughter of 95-year-old Clare Nowland demonstrates key principles of the rule of law including the presumption of innocence, the independence of the judiciary, the separation of powers, and the significance of fair and prompt trials. It also raises important questions about bail, the duty of care owed by police officers and the role of the media in the justice process.

This case note will review the details of the case and examine how principles of the rule of law were applied during the criminal trial process. It will also consider the broader implications for the NSW justice system given the offence was committed by a police officer in the course of duty.

Facts of the Case

Clare Nowland was a 95-year-old resident of an aged care facility in regional NSW. She showed signs of the symptoms of dementia but was not diagnosed and used a 4-wheel walker for mobility.

On the 17th of May 2023 at around 2am, she was found by facility staff wandering the halls of the facility with her walker and two steak knives. After some time attending different areas of the facility, including the kitchen and rooms of some other residents, Mrs Nowland became seated in a nurse’s office in the administration area. She was still in possession of one knife.

A registered nurse from the facility contacted emergency services for assistance with the situation from Ambulance officers. Two paramedics and two police responded, including Senior Constable Kristian White, a police officer with 12 years’ experience. They encountered Mrs Nowland in the nurses’ room still holding the serrated knife.

After approximately two hours of attempts by facility staff and further attempts by emergency services to convince her to relinquish the knife, Mrs Nowland refused. She began to walk slowly toward them using her walker with the knife, whereupon White then discharged his taser on Nowland, causing her to fall backward, striking her head and causing a head injury. Approximately three minutes had elapsed between White arriving at the scene and the discharge of his taser.

Mrs Nowland passed away one week later on 24 May 2023 in Cooma Hospital due to the injury sustained as a result of the tasering.

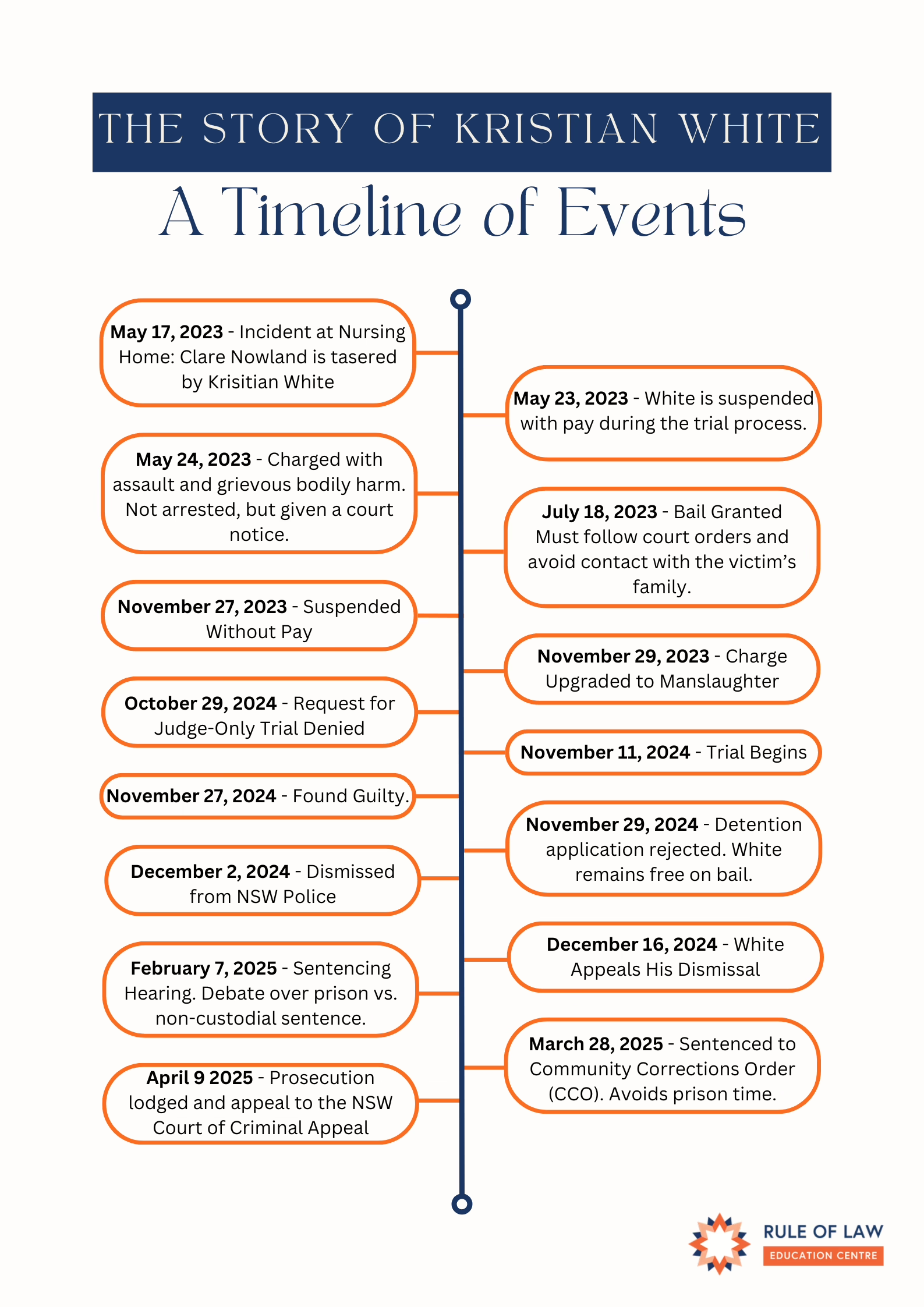

Procedural History

May 2023: Initial Charges Laid

Upon Mrs Nowland’s death, White was charged with three offences under the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW):

1. Reckless grievous bodily harm (s35);

2. Assault occasioning actual bodily harm (s59); and

3. Common assault (s61).

White was issued a separate Court Attendance Notice (CAN) for each offence. No bail conditions were placed on him by police at the time the CANs were issued.

What is a Court Attendance Notice?

A CAN is a legal document that notifies an individual (and the court) that they have been charged with a criminal offence. It will provide information about the crime they have been charged with, a brief description of the allegations made against them, and details of the time, date and place of the court complex they must attend to answer the charge(s). It can be delivered by mail or in person and can be accompanied by other documents, such as fact sheets from the prosecutor outlining their version of events or a bail undertaking, which is the agreement of the individual to their bail conditions.

While both a CAN and bail serve the same ultimate purpose – ensuring the individual appears in court – they are different. A CAN is simply a notice to attend court, whereas bail is an agreement that allows the person to remain out of custody while waiting for their court date and includes conditions or restrictions on their behaviour or movement.

July 2023: Detention Application

Following the issue of the CANs, the prosecution lodged a detention application in the Supreme Court under s50 of the Bail Act 2013 in order to have bail conditions imposed on White.

In the application, the prosecution requested three bail conditions be imposed:

-

- To be of good behaviour;

- To appear at court as directed; and

- Not to approach or communicate with the family of the deceased or any prosecution witness except through a legal representative.

The presiding Judge, Justice Robert Beech-Jones accepted these conditions, and White was officially granted bail on July 18, 2023.

November 2023: Charges Upgraded

The charges against White were upgraded to manslaughter on 29 November 2023 on the advice of the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP). White pleaded not guilty.

October 2024: Application for Judge Alone Trial

R v White [2024] NSWSC 1369

White’s defence team made an application to the court seeking permission for a judge alone trial on October 14, 2024. The application was made on two grounds:

-

- That members of a potential jury would have been influenced by adverse publicity from the wide media coverage the case had received and that judicial directions could not mitigate the prejudice; and

- The complex nature of the legal issues required in the legislation to prove the two bases for liability of involuntary manslaughter – criminal negligence or unlawful and dangerous act (see diagram on page 4).

On October 15, 2024, Justice Yehia of the NSW Supreme Court refused White’s request for a judge-alone trial, ruling that the negative media coverage was not shown to have been viewed recently enough by a large percentage of the population, and that, as a result, there was not an unreasonable risk that potential jurors would be affected.

Her Honour also ruled that the legal issues were not too complicated for a jury to understand with standard legal instructions. Her Honour noted:

“In relation to the law, the jury will be assisted by way of directions… about the elements of the offence and directions in relation to the two bases of liability… I am not of the view that the issues in the trial involve a level of complexity militating in favour of a judge alone trial.” [71]

November 2024: Trial

White’s trial began on 11 November 2024 in the Supreme Court of NSW. It was presided over by Justice Ian Harrison and had a 12-person jury composed of 4 men and 8 women. The trial went for 8 days, with the jury deliberating for 5 days before reaching a verdict. On 27 November 2024, the jury found White guilty of manslaughter. Sentencing was reserved until February.

November 2024: Detention Application

R v White [2024] NSWSC 1527

Following the guilty verdict, the Prosecution made a detention application under s22B of the Bail Act 2013 to hold White in custody until the sentence was delivered.

The application was based on the assumption that there was a strong likelihood that White would receive a custodial sentence. Justice Harrison was of the view that, given the wide range of options for sentencing available to the conviction of manslaughter, a decision to hold White in custody would preempt his decision on the sentence.

“I am… particularly troubled that a decision to either continue Mr White’s bail or revoke it carries in each case at least the possible appearance of prejudgement when I finally come to decide what sentence to impose.” [14]

This application was rejected. Justice Harrison decided that the original three bail conditions would continue until sentencing.

February 2025: Sentencing Submissions Hearing

On the 7th of February, 2025, Justice Ian Harrison heard sentencing submissions from both the Prosecution and Defence. These included 14 Victim Impact Statements read out loud to the court from Mrs Nowland’s family members, and a letter of apology from Mr White. His Honour reserved his decision, adjourning the matter to a later date.

March 2025: Sentencing Decision

R v White [2025] NSWSC 243

Given the wide and varied range of circumstances that can lead to an event of manslaughter, the offence carries a wide range of sentencing options from non-custodial orders to a maximum sentence of 25 years imprisonment (s24 Crimes Act 1900). Sentences imposed previously have varied significantly due to the individual nature of the cases before the courts, and specifically to cases of involuntary manslaughter, the absence of mens rea.

After receiving sentencing submissions on February 7, 2025, Justice Harrison delivered his sentencing decision on March 28, 2025. Justice Harrison sentenced White to a 2-year Community Correction Order (CCO) commencing the day of the sentencing. He also added that White complete 425 hours of community service work.

April 2025: Prosecution Appeal

The prosecution launched an appeal to the Court of Criminal Appeal on 9 April 2025, based on three key grounds:

-

- Inadequate Sentence: The sentence imposed was too lenient.

- Error of Fact: The judge mistakenly believed there was agreement that the offender honestly thought his actions were necessary.

- Sentencing Errors: The judge misjudged the seriousness of the offence and wrongly minimised the importance of general deterrence in sentencing.

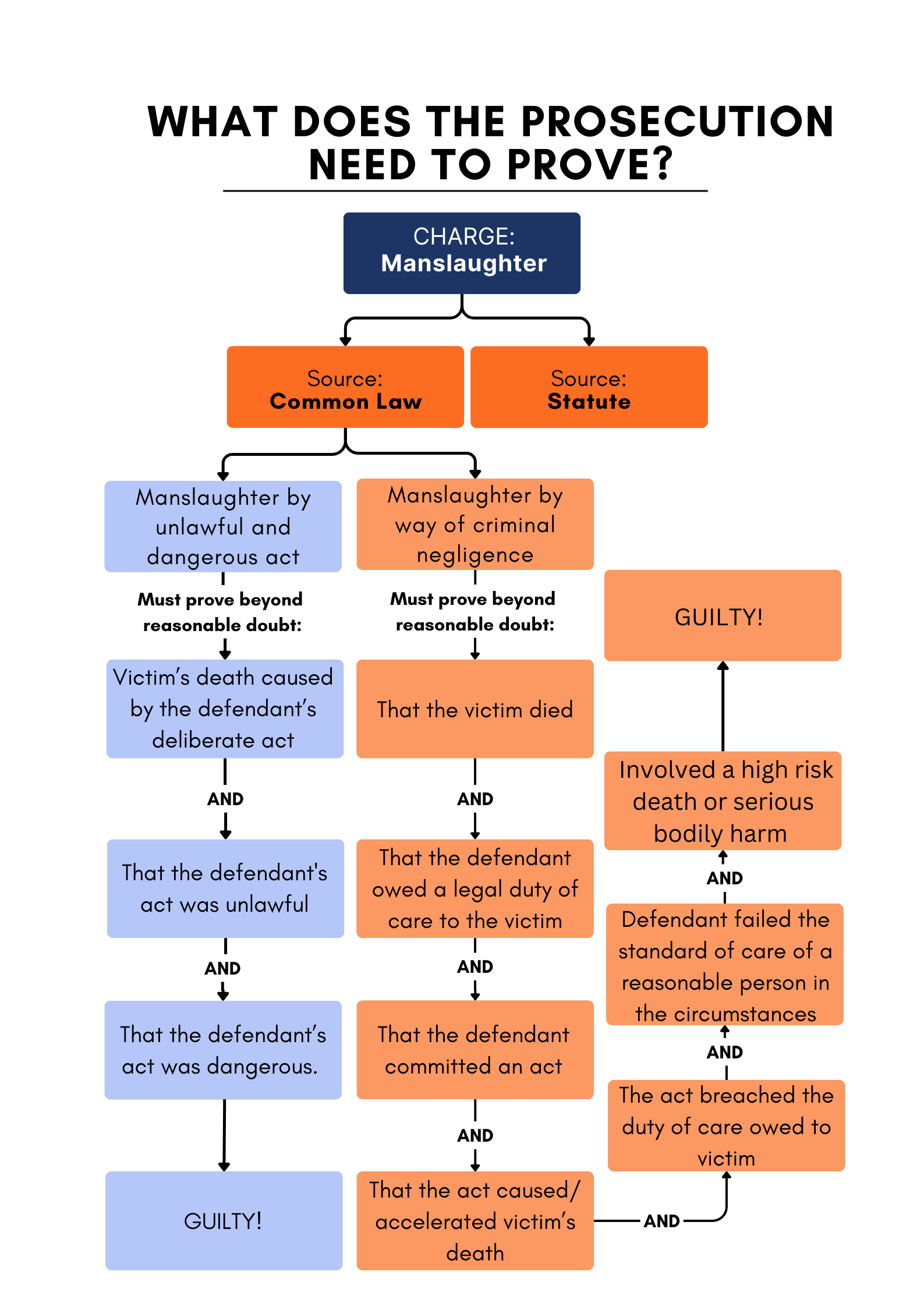

What is Manslaughter?

Manslaughter is a type of unlawful killing (homicide) and is an indictable offence. The key difference to this type of killing with that of a murder is the ‘intent’ (mens rea) of the accused. For murder, the accused must have had a reckless indifference to human life, or an intent to kill or inflict grievous bodily harm upon the person (Crimes Act 1900 NSW s18(1)(a)). This requirement does not apply to a charge of manslaughter.

Manslaughter is defined in both statute and common law. At statute law, it is defined as every punishable homicide that does not meet the definition of murder (Crimes Act 1900 NSW s18(1)(b)). Manslaughter can broadly be categorised as either voluntary or involuntary.

Voluntary manslaughter is regulated by the statute law. S18(1)(b) of the Crimes Act 1900 NSW, a murder charge can be reduced to manslaughter by reason of:

-

- Provocation (s23) – the accused was provoked into an act; or

- Substantial impairment (s23A) – the accused was suffering mental ill health or cognitive impairment; or

- Excessive self-defence (s421) – whereby, according to the Act, “the conduct is not a reasonable response in the circumstances as he or she perceives them, but the person believes the conduct is necessary…” This form of manslaughter can also be categorised as involuntary.

Voluntary manslaughter can also be described as ‘defences’ to murder. If an accused person chooses to use a defence of provocation or excessive self-defence, the prosecution then bears the onus of disproving it beyond a reasonable doubt (i.e., the prosecution must prove that the accused was not provoked or acting in self-defence).

It is important to note that with the defence of substantial impairment, the burden of proof moves to the defendant. To be charged with manslaughter by reason of substantial impairment, the accused person must prove on the balance of probabilities that they were suffering from a substantial impairment at the time of the murder.

How would the use of defences like these help to achieve a just outcome for accused persons?

How do defences impact on the rights of the victim?

In contrast to this, involuntary manslaughter is defined in Common law. It can be either:

-

- Manslaughter by unlawful and dangerous act; or

- Manslaughter by criminal negligence.

To secure a conviction of involuntary manslaughter, the prosecution only needs to prove one of these types beyond a reasonable doubt.

Given that White was not charged with murder, involuntary, common-law manslaughter was the only option available to prosecute for the death of Mrs Nowland. The prosecution chose to pursue both types.

Legal Issues

Bail

The issue of bail following a conviction of manslaughter highlights the tension between the rights of the victim and offender.

(For information on what bail is and recent reforms in NSW, see our Bail resource at https://www.ruleoflaw.org.au/crime/criminal-investigation-process/introduction-to-bail-and-the-bail-process/)

Following his conviction of manslaughter, Justice Harrison ruled to continue White’s bail until sentencing occurred in early 2025. This decision sparked widespread debate given the strong public sentiment regarding the death of Mrs Nowland.

His Honour noted several reasons for this decision:

-

- There is no automatic jail sentence for manslaughter, which means judges must carefully consider all factors before deciding on a sentence;

- Given his status as a former police officer, there were real risks to his safety posed by other inmates should he be sent to a correctional facility while awaiting sentence;

- White had complied with all of his bail conditions prior to the verdict;

- He had no prior criminal record; and

- There was no evidence that releasing him posed a threat to public safety or the legal process.

However, this outcome was deeply troubling for many people, especially Clare Nowland’s family. Some felt that allowing White to remain free whilst awaiting his sentence downplayed the seriousness of the offence and associated conviction and reflected unfair treatment because of White’s status as a police officer.

The long gap between the conviction in November 2024 and the sentencing in March 2025 added to these concerns. Although such delays are common in complex cases, to allow time for the court to properly assess all relevant sentencing factors, it can feel like justice is being postponed and can cause frustration for those seeking closure or accountability.

Police Powers, Duty of Care and the Use of Force

The White case highlighted the challenges police face in fulfilling their duty of care to different parties when responding to incidents, especially when dealing with vulnerable people. It also draws attention to police powers and the use of force in unusual situational contexts.

The public expects police to be guided by their obligations under the duty of care in all situations. Compliance with this legal principle creates and maintains public trust confidence in the legal system and in the work of the police. This sentiment was reiterated by Justice Harrison in his sentencing decision:

“…the duty of care owed to any member of the public by a police officer is fundamental. The community places great store in the fact that an officer will only use force in the course of his or her lawful duty that is both reasonably necessary and proportionate in the circumstances.”[18]

R v White [2025] NSWSC 243

In the course of their duties, police are given significant powers, including the use of force, but they are expected to exercise those powers responsibly. This means acting reasonably in a manner that is proportionate to the situation at hand, using force only when necessary, and taking steps to minimise harm. In addition, there are a number of protocols that guide and regulate police behaviour when responding to different incidents that are designed to ensure these standards are upheld by all police officers.

One of the more complex aspects of the duty of care for emergency responders such as police is that it will often extend to several people at once. In this case, White had responsibilities not just to Mrs Nowland, but also to the staff and other residents of the aged care facility, his police partner, and the paramedics on scene. When those duties come into conflict, officers are forced to make decisions about whose safety takes priority in that moment.

This case raises important questions about how those decisions are made in practice and has prompted wider discussion about how police interact with people who are elderly, frail, or cognitively impaired. It has also highlighted whether current training, procedures and protocols are adequate for the myriad situations that police officers encounter in the course of their duties, and the expectations that police officers should always be able to determine the right course of action given the circumstances they are facing.

Non-Legal Responses

Media and Social Media

The role of media and social media in shaping public opinion presents complex challenges for ensuring just outcomes in the legal system.

In White’s case, during his application to the Supreme Court for a judge-alone trial, he argued that widespread and “vitriolic” pre-trial publicity had occurred and would prevent an unbiased jury from being selected and a fair trial from being conducted. Justice Yehia presided over the application.

A comprehensive list of media articles and social media posts was tendered to the court during this hearing, some with up to 15 million ‘likes’. Amongst the reporting and commentary on the incident, some of the coverage portrayed him as guilty, erroneously stated that he had tasered the victim twice, referred to a previous case where misconduct had occurred which White had also attended (but had no finding of misconduct made against him) and some of which also called for retribution.

The court ultimately agreed with the Crown’s submissions, noting that much of the material (e.g., news articles and TikTok videos) dated back several months and there was no evidence it had been recently viewed or had a widespread impact. In her judgement, Justice Yehia stated:

“Proceedings such as these will invariably attract some publicity in mainstream media forums as well as commentary in the online world. The nature and extent of that will vary from case to case…. Some practices have been adopted by the courts to meet the changing circumstances brought about by technological advancement in an effort to protect the right to a fair trial. These practices include model judicial instructions and warnings to jurors…”[49-50]

“To the extent that any of the reporting included information inconsistent with the Crown evidence, it is highly unlikely that such misreporting will have a prejudicial effect in this case given that the entire incident was captured on BWV [Body Worn Video] footage.”[59]

“Having considered all of the articles and social media posts relied upon in support of the application, I am not of the view that it is in the interests of justice to make an order for a judge alone trial.” [68]

The court also found that the commentary identified was either obviously biased or lacking in credibility and did not rise to a level that would prevent a fair trial. This outcome highlights that while media and social media commentary can be emotive and inflammatory, its impact on the fairness of legal proceedings must be demonstrated with concrete evidence. Courts do not assume prejudice has occurred without clear proof that such content has influenced public perception to a degree that would compromise a fair trial for the accused.

Further, the essence of the coverage and opinions expressed that may be shared also impacts upon public confidence in the justice system. Police, Courts and judges are all bound by rules set down in law to ensure due process is followed, fairness is achieved and equality before the law is recognised. Media and social media coverage of trials and sentencing outcomes do not always publicise the legal reasoning for outcomes or decisions, and can either act to instil or erode confidence in the legal system depending on the perspectives shown.

Rule of Law Principles

The Presumption of Innocence

All defendants in criminal cases in Australia have the right to the presumption of innocence, meaning that they are presumed to be innocent of the crime until it can be proven by evidence, beyond a reasonable doubt, in a court of law, that they committed the crime they have been accused of.

At international law, the presumption of innocence is protected by Article 14 (2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). In NSW, it is legislatively protected under s141 of the Evidence Act 1995:

“In a criminal proceeding, the defendant is presumed to be innocent of the alleged offence until the prosecution proves the defendant’s guilt.”

This principle ensures that the burden of proof remains entirely on the prosecution and ultimately seeks to protect against wrongful conviction.

Throughout the trial, the jury could not convict White of manslaughter unless they were satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that every element of the offence of manslaughter had been proven by the evidence before the court, upholding the presumption of innocence.

In addition to upholding the presumption of innocence, ensuring the prosecution must prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt is also required because of the imbalance of resources between the Crown and the defendant to prove their case. The Crown is part of the Executive arm of government, and has access to law enforcement, expert legal teams, and extensive financial resources, while the defendant usually has significantly less resources with which to defend themselves.

Judicial Independence and the Separation of Powers

In Australia, judicial independence is upheld by the doctrine of the Separation of Powers, as outlined in the Constitution. This framework assigns judicial authority exclusively to the courts, ensuring that judges operate free from interference by the Legislative or Executive branches. At international law, Article 14(1) of the ICCPR guarantees the right to a fair hearing before an independent and impartial tribunal, further supporting the principle of judicial independence.

In order to maintain the integrity of the judicial arm of government in Australia, judges:

-

- Are granted security of tenure (a guarantee that they cannot be fired unless they commit a serious crime);

- Are paid high wages that are transparently outlined in legislation to prevent bribery and reinforce their autonomy and impartiality; and

- Take an oath to uphold their responsibilities with integrity rather than signing a contract of employment with the Executive. In the oath, judicial officers swear to treat all people “without fear or favour, affection or ill-will”, meaning that they will treat all people before the court equally.

These measures act to protect the independence of the Judiciary from undue pressure or influence from the Parliament and Executive.

When considering the Separation of Powers, White’s case is particularly interesting because, at the time of the incident, he was acting in his official capacity as a police officer – a member of the Executive branch of government – and was performing a role of law enforcement at the time, a role that somewhat overlaps with that of a judge.

Despite Mr White’s role, the Court was not biased in his favour, nor was it improperly influenced to protect him from legal consequences due to the crime’s commission during the course of his official duties. The fact that he was tried and convicted through due process demonstrates the courts’ ability to hold individuals accountable and ensure that the law is applied equally and fairly to all people in the community.

This case also highlights the critical role of the Separation of Powers in maintaining a fair and just legal system that upholds equality before the law for all people, regardless of who they are. By keeping the Judiciary separate from the Executive, the legal system provides an essential check and balance on the abuse of power. Without this separation, there would be a risk that public sector employees could evade accountability, which would ultimately undermine public trust in the legal system.

Fair and Prompt Trials

The right to a fair and prompt trial is a common law right. There are a number of protections for this right built into the procedures and processes of the Australian legal system. These guarantee key legal safeguards, including an independent and impartial court, public hearings, the presumption of innocence, timely trials, legal representation, and protection against self-incrimination and double jeopardy. They ensure due process is followed in all cases across the court hierarchy and uphold justice for individuals facing criminal charges. It is also protected under Article 14 of ICCPR.

The White case shows many of the elements that are designed to protect accused people. As discussed previously, White was afforded the presumption of innocence, given the opportunity to present his defence, his case was heard by an independent jury, with a judge presiding who ensured that the rules of evidence applied and that there was procedural fairness for both parties. Although his application was ultimately rejected, he was able to apply for consideration for a judge alone trial given the publicity the case had received, with its potential impact examined by an impartial judge who followed due process and provided sound legal reasons for her decision. A jury of randomly selected community members considered the evidence and made a considered decision as to White’s guilt.

In her decision regarding White’s application for a judge-alone trial, Justice Yehia outlined some of these factors as being important protections of a fair trial.

“The interests of an accused are not necessarily the interests of justice. The community receives important collateral benefits from a trial by jury in the involvement of the public in the administration of justice and in keeping the law in touch with the community standards…”[29]

“Acknowledging that the interests of justice are not limited to the interests of an accused, does not detract from the emphasis that should be placed upon the fundamental importance of an accused receiving a fair trial. Underpinning that principle is the presumption of innocence and the substantial consequences that flow to an individual upon a finding of guilt. Furthermore, the interest of the community is not in ensuring that an accused is convicted but in ensuring that an individual accused of a crime receives a fair trial according to law.”[30]

It is also worth noting that White’s trial proceeded without excessive delay, with charges initially laid in mid-2023, and a verdict reached by November 2024. This timely process helped preserve witness memories, reduced emotional and legal uncertainty, and still allowed both parties adequate time to prepare their cases thoroughly.

Sentencing Submissions

Prior to deciding on a sentence, the court will hear sentencing submissions from both parties. These are designed to allow both the prosecution and defence the opportunity to submit any information that is of relevance to the sentencing decision. Sentencing decisions play an important role in ensuring fairness is achieved for the offender, whilst taking into account the impact of the crime on the victim and other relevant parties.

The sentencing submissions in the case of Mr White were heard on February 7th, 2025, which included 14 Victim Impact Statements read to the court by the family members of Mrs Nowland, a letter of apology written by Mr White and evidence of Mr White expressing remorse to a forensic psychologist.

People can only be punished in accordance with the law

R v White [2025] NSWSC 243

While unlawful deaths are treated very seriously by the legal system, there is a wide range of circumstances where unlawful death may occur, with each case having unique circumstances.

Given the lack of intent that is a component of manslaughter, accounting for the unintentional nature of a death whilst determining a sentence that reflects the seriousness of the offence clearly shows the conflict between the rights of the victim and the offender. As such, a wide range of sentencing options are available for the offence of manslaughter, ranging from non-custodial orders to a 25-year term of imprisonment.

When sentencing, a judge will consider not only the specific circumstances of the crime, but also a number of other factors including any mitigating factors and the objective seriousness of the crime – that it, how serious was the offence compared to other instances of the same offence. These measures are designed to ensure that the sentence is reflective not only of the seriousness of the crime, but also of circumstances unique to the case before the court.

In this case, White was sentenced to a 2-year Community Correction Order with 425 hours of community service.

A CCO is a type of ‘non-custodial’ sentence that allows offenders to serve their sentence in the community under specific conditions and supervision rather than going to jail. CCO’s have two standard requirements:

-

- The offender must not commit any offences; and

- The offender must appear before the court if called upon during the time of the order.

In White’s case, Justice Harrison considered a number of factors, including the complexity of balancing the rights and needs of victims, offenders and the community:

“Sentencing is a complex and complicated task… unlike theatrical or cinematic representations of this aspect of the criminal law, sentences in this country are not handed down without giving due consideration to a very large number of important and often contradictory themes.”[14]

Throughout his sentencing decision, His Honour referred to many considerations, including:

-

- The basis of liability: submissions from both parties regarding the duty of care owed by police officers to members of the public and the considerations of how that was impacted in these circumstances;

-

- Objective seriousness: the unique circumstances that determine the gravity of the offence and the moral culpability of the offender in comparison to similar instances of the same offence. This aspect examined the uniqueness of the circumstances and that there was no other similar offence to compare it with, the vulnerability of Mrs Nowland, the fact that White was a serving police officer, the physical disparity between the victim and offender, and the short time of 3 minutes between White first seeing Mrs Nowland and the discharge of the taser;

-

- Subjective considerations (specific to White himself): criminal history, remorse, good character and mental state;

-

- Deterrence: general (deterrence of others) and specific (deterrence of the offender themselves);

-

- Victim impact statements: received by the court during the sentencing submissions hearing from children and close relatives;

-

- Legislation: s3A Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act, containing the purposes of sentencing and s5, specifying the legal reasoning for giving a penalty of imprisonment; and

-

- Community expectations: the community considers harm to elderly persons to be particularly wrong.

Eventually, Justice Harrison held that the crime was one that was the result of a serious error in judgement on White’s behalf and fell on the lower end of objective seriousness:

“I am unable to conclude that Mr White’s negligence was either gross or wicked. The simple but tragic fact would seem to me to be that Mr White completely, and… inexplicably, misread and misunderstood the dynamics of the situation that he faced and patently overestimated both the existence and the level of the threat created by Mrs Nowland in the circumstances.”[26]

“It is beyond controversy that the death of any person is serious. The death of Mrs Nowland is no different. The notion of objective seriousness does not call that fact into question and instead deals with an entirely different concept, being a comparison, if that is possible, between Mr White’s offence and other similar offences.”[35]

“…a custodial sentence would in my view be disproportionate to the objective seriousness of the offence and Mr White’s particular subjective circumstances.” [87]

Conclusion

The White case provides a good example of how fundamental rule of law principles operate within the Australian legal system. It reaffirmed the presumption of innocence, the importance of an independent judiciary, and the role of fair and prompt trials in ensuring justice. Additionally, it prompted public discussion about the justifications for bail, the complexities of the duty of care that police officers owe, and the appropriate use of force by law enforcement.