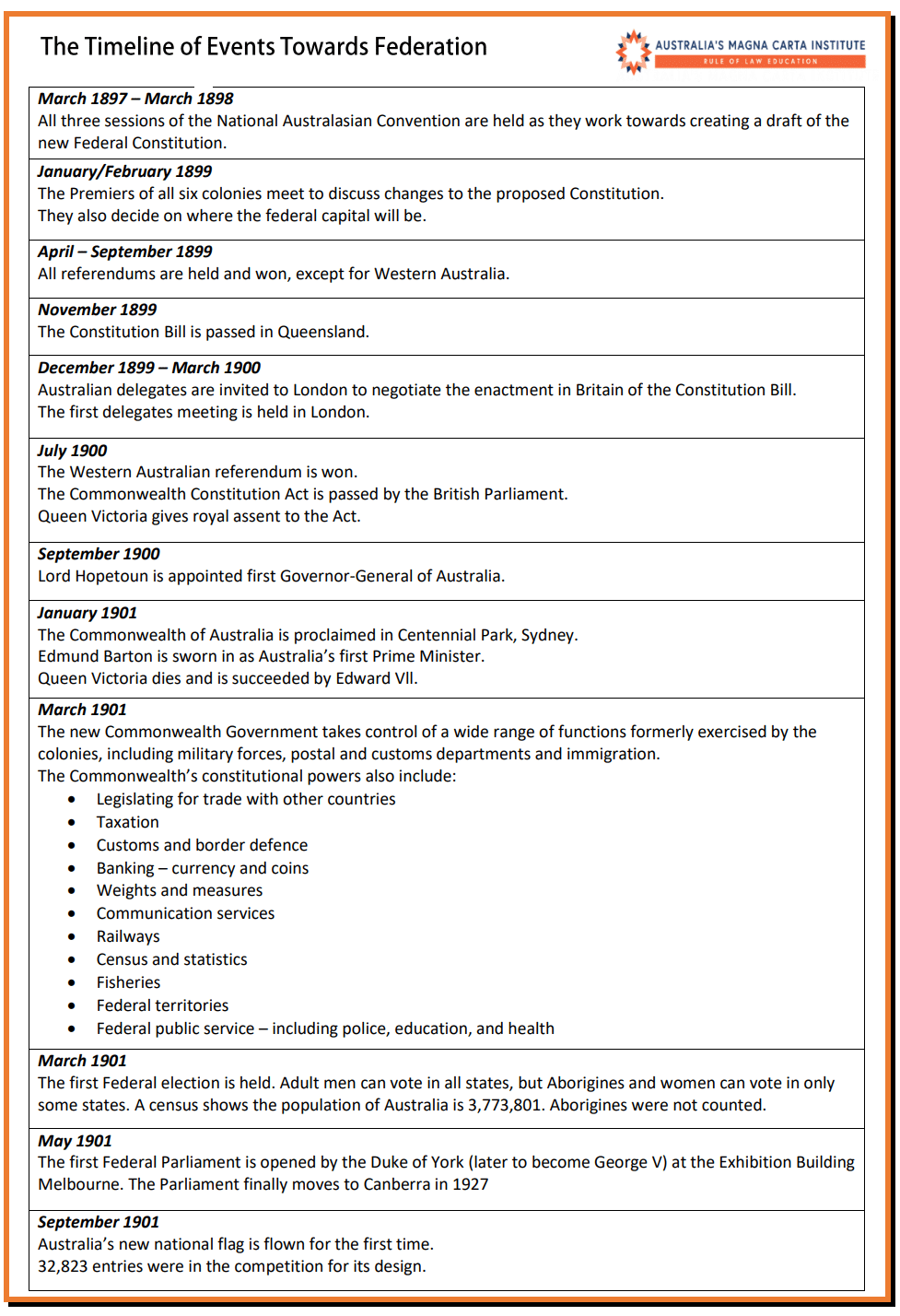

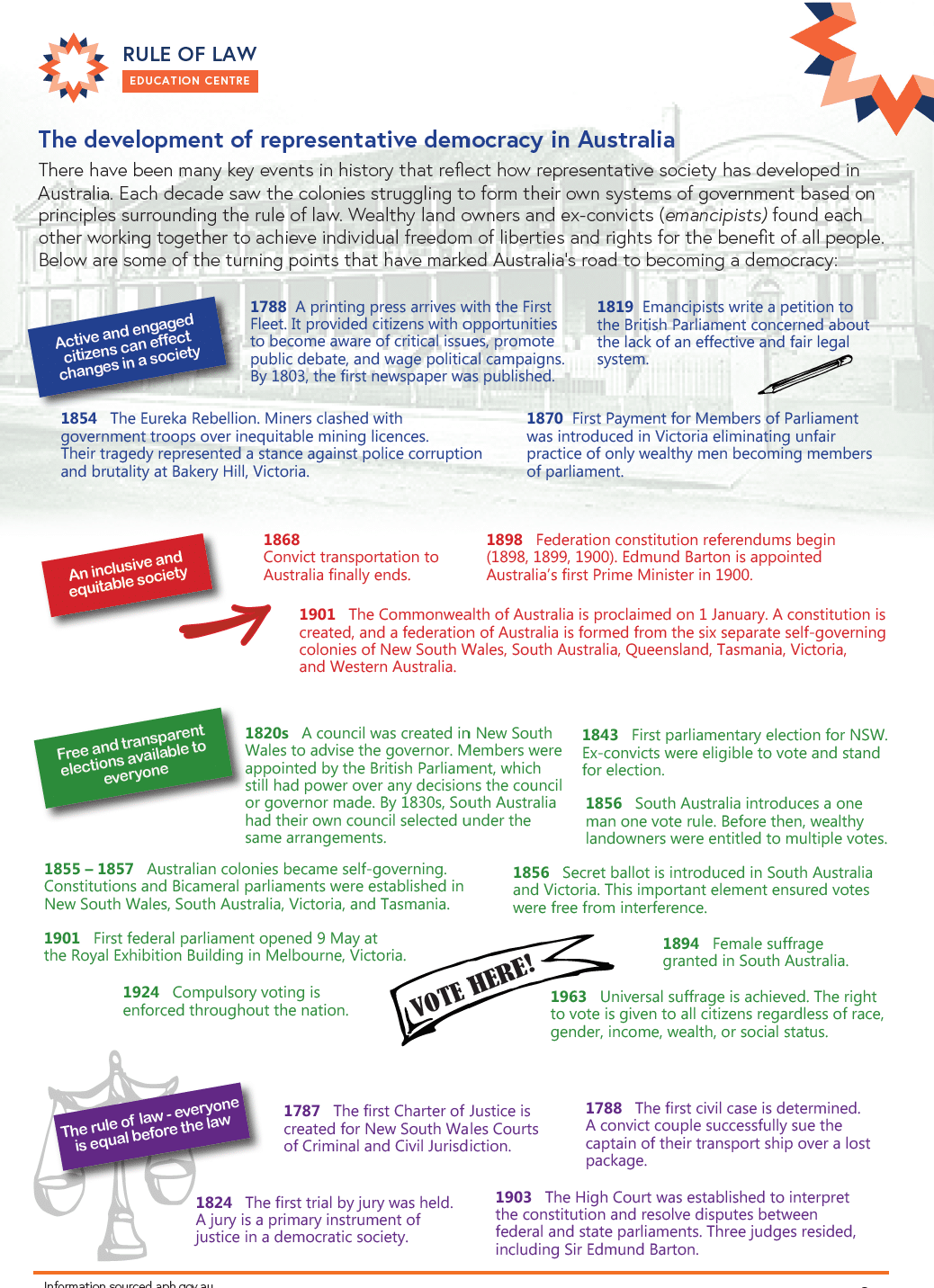

The Australian Constitution

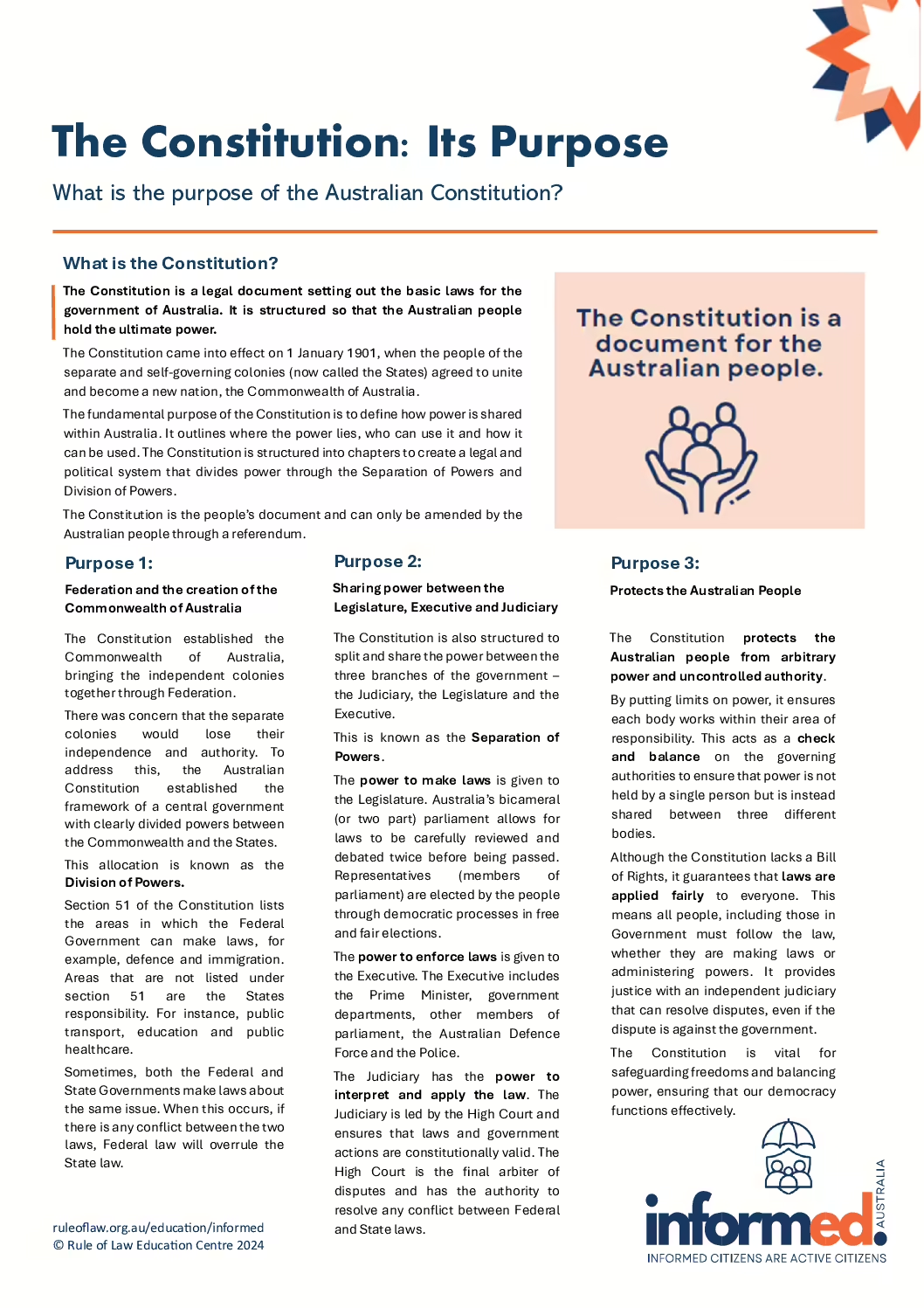

The Australian Constitution provides the legal framework for how Australia is governed.

The Constitution establishes how the Commonwealth system of government is operated in Australia. It defines how laws are made and how power is distributed between the federal, state and territory governments. This is known as the division of powers. The Constitution also outlines the role of federal parliament and how the powers are shared between the legislature, executive and judiciary. This is called the separation of powers. The division of powers and the separation of powers provide fundamental foundations in establishing and maintaining the rule of law for all citizens living in Australian society.

Principles

The Constitution ensures Australia operates under the rule of law.

The Separation of Powers

Power is disbursed across three branches of government; Legislature, Executive and Judiciary.

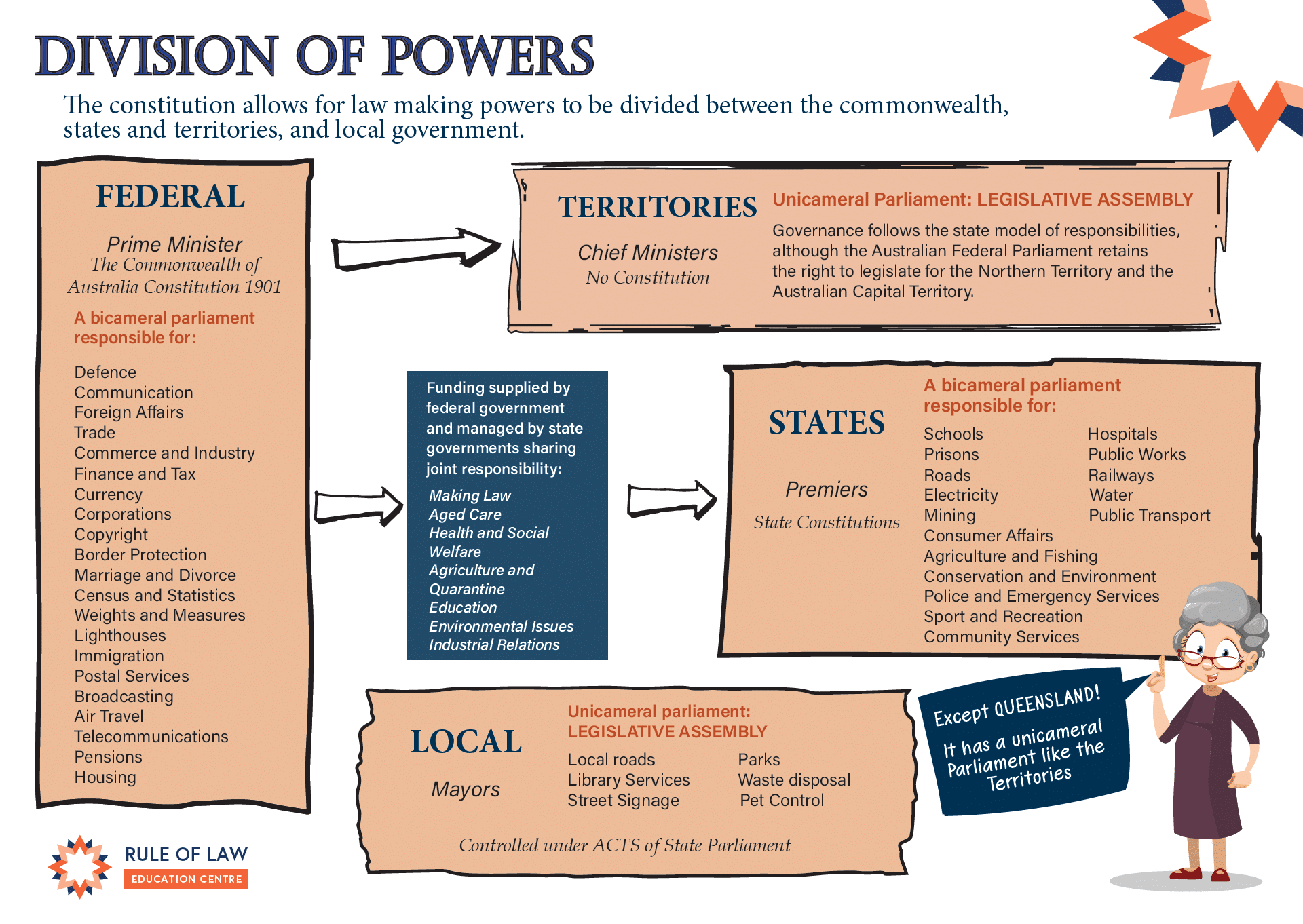

Division of Powers

Power is divided between the federal, state and territory governments.

Human Rights

Rights are protected by democracy, with only a few express rights.

Overarching Principles of the Constitution

The Constitution is a document of the Australian people which establishes rules for the governance of our nation.

The Constitution protects the Australian people from arbitrary power and uncontrolled authority. It provides a predictable and orderly society with important checks and balances promote justice, fairness, and individual freedom. The Constitution guarantees that all Australians enjoy essential protections based on the principles of the rule of law. It does this by establishing a framework for the operation of government with their powers clearly articulated into Chapters and Sections:

- How the Federal Parliament works and what powers it has (Chapter I)

- The composition of the Australian Parliament (Chapter I)

- How the Federal and State Parliaments share power (Chapters V & VI)

- The role of the executive government (Chapter II)

- The role of the High Court of Australia (Chapter III)

- How the Constitution can be changed (Chapter VIII)

By limiting power, it ensures each body works within its area of responsibility. This acts as a check and balance on the governing authorities to ensure that a single person does not hold power but is instead shared between three different bodies. The Constitution provides that the Commonwealth government will be both a representative and responsible government operating under the rule of law.

The ‘rule of law’ rather than the ‘rule of men’: Clause 5

The rule of law is a principle which is implied in our Constitution.

It is the idea that all Australians should be governed by a clear set of rules applied fairly and equally to everyone, regardless of their status. This supports the idea that a person cannot be punished or have their rights adversely affected other than in accordance with the law and only after a breach of the law has been established. Effective governance includes practicing principles derived from the rule of law; such as, the legal system should be easily understood and accessible to all citizens. This principle aims to ensure that the powers of government will be exercised in accordance with pre-existing laws. Laws that are written, publicly disclosed, administered justly and fairly, and in accordance with established procedural steps, and which are consistently adopted and enforced. Similarly, the Constitution imposes limits on government to protect against the use of arbitrary power.

Clause 5 in the Constitution states:

‘all laws made by the Parliament of the Commonwealth under the Constitution, shall be binding on the courts, judges, and people of every State and of every part of the Commonwealth..…’

This clause states that everyone will be governed by and bound by the laws of Australia. No one is above the law, and everyone is entitled to due process if they are potentially subject to Commonwealth law, including institutions, corporations, government agencies, and individuals.

To facilitate this, the Constitution ensures that judicial power is independent and impartial. The separation of powers allows laws to be applied fairly, and if a legal wrong occurs, a remedy can be sought from an independent judiciary. Specifically, Clause 75 of the Constitution states:

‘(v) in which a writ of Mandamus or prohibition or an injunction is sought against an officer of the Commonwealth; the High Court shall have original jurisdiction.’

This ensures that the actions (or failures to act) of Members of Parliament are subject to judicial review, at least in the original jurisdiction of the High Court. This accountability ensures they act within their lawful powers, meaning they are subject to the law and do not exceed the authority that the law or Constitution grants them.

Furthermore, the Constitution protects the independence of the judiciary by outlining the tenure and terms of service for judges. These provisions maintain the judiciary’s independence, which is crucial for ensuring that laws made by the Legislature and actions of the Executive are lawful and consistent with the Constitution.

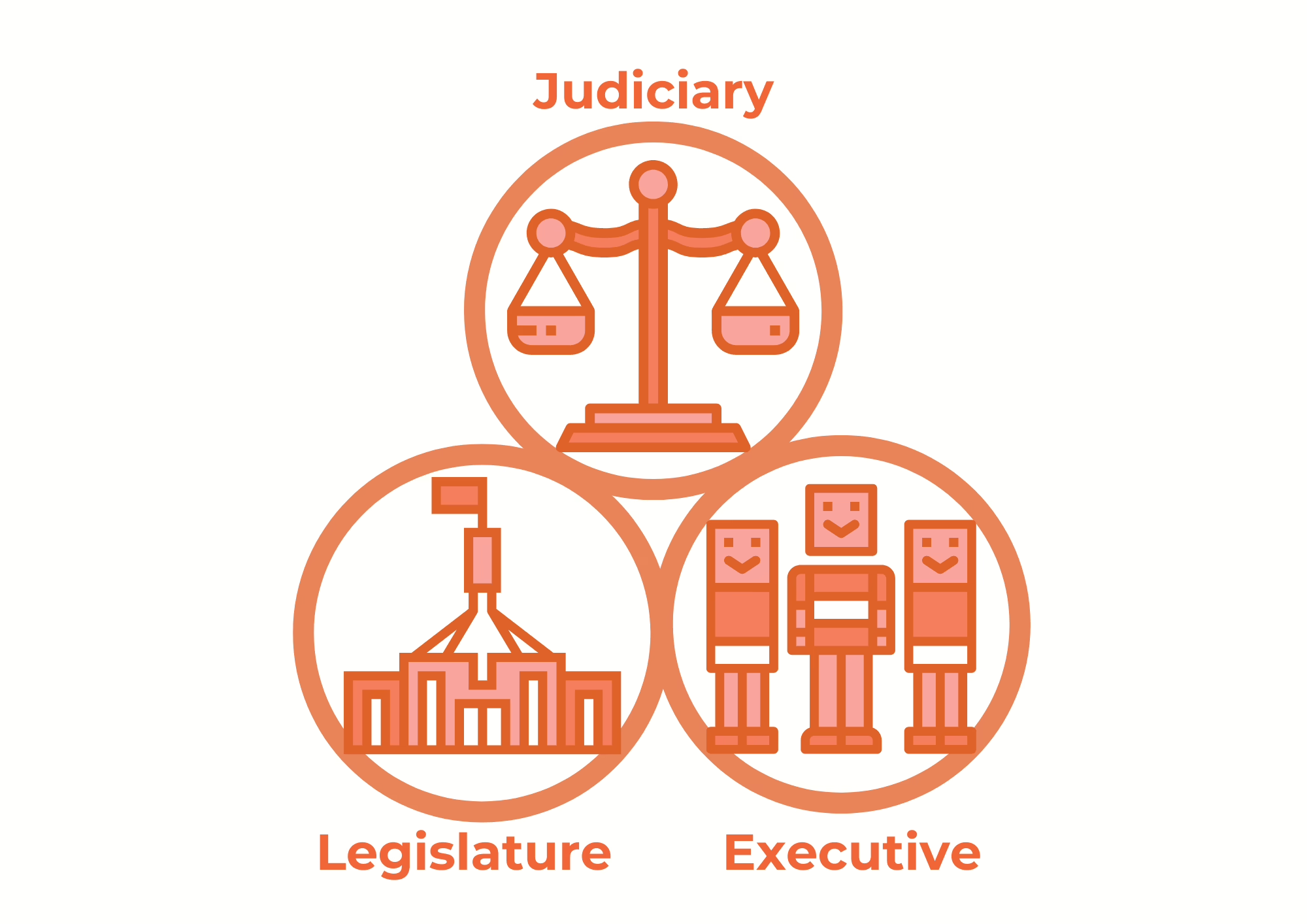

Separation of Powers: Chapters I to III

The Australian Constitution divides power between three branches of government referred to as the separation of powers.

Chapters I to III of the Constitution outlines the legislative, executive and judicial powers of the Commonwealth as the three separate branches of government. The Constitution includes checks and balances for the exercise of government power to ensure the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The doctrine of separation of powers ensures that power isn’t vested in a single set of hands, but is disbursed across three branches of government:

Has the power to make and change laws. Parliament is made up of representatives who are elected by the people of Australia.

Has the power to enact law and administer the business of government through government departments, statutory authorities and the defence forces. The Executive includes Australian government ministers and the Governor-General.

Has the power to interpret law and conclusively determine legal disputes. Courts and judges are independent of parliament and government.

Despite the structure of the Constitution and the ideal of the doctrine of separation of powers, there is no strict demarcation between the legislative and executive powers of the Commonwealth. Only Parliament can pass laws, which are then conferred on the Executive government to make regulations and rules (or by-laws) in relation to matters relevant to the particular laws.

CASENOTE: R v Kirby; Ex parte Boilermakers’ Society of Australia (1956)

Pivotal Constitutional law case about Separation of Powers and highlighted that only Chapter III courts can exercise the judicial power of the Commonwealth; and Chapter III courts cannot exercise any non-judicial power.

CASENOTE: Australian Communist Party v Commonwealth (1951)

The Communist Party case represents a shining example of the power of a court to compel a democratically-elected government to obey the constitutional rules set down half a century before.

CASENOTE: Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW) [1996]

Important case regarding Separation of Powers where the constitution provides for an integrated judicial system in Australia, where State courts can exercise federal jurisdiction with the limitations placed on federal courts having some role to play in state courts too.

CASENOTE: NZYQ and the Separation of Powers

In NZYQ, the High Court considered the constitutional validity of laws that allowed the Australian Government to indefinitly detain ‘NZYQ’, an unlawful, non-citizen convicted of child sexual assault. He had completed a prision sentence but, due to his criminal record and statelessness, had no reasonable prospect of deportation back to his home country or any other country

CASENOTE: Love v Commonwealth; Thoms v Commonwealth [2020]

Historic High Court decision which considered the scope of the ‘aliens’ power in respect of two non-citizen Aboriginal Australians. In this case, the High Court was tasked with ascertaining whether the scope of ‘aliens’ provided by s 51(xix) included non-citizen Aboriginal Australians.

EXPLAINER: Dual Citizenship debate 2017

Interpretation of Section 44 of the Constitution.

In 2017, six members of Parliament were found to be dual citizens and therefore disallowed to hold office under s. 44 of the Constitution. Click here to for case summaries and our analysis of the Dual Citizenship debate.

EXPLAINER: Reserve Powers: Whitlam Dismissal

In some situations, the Governor General may exercise reserve powers. It is generally accepted that the Governor General’s reserve powers include the power to appoint a Prime Minister if an election results in a hung parliament; the power to dismiss a Prime Minister when the House of Representatives has passed a motion of no confidence against the Prime Minister; and the power to refuse to dissolve the House of Representatives contrary to ministerial advice. Click here to read our post about the Gough Whitlam dismissal and reserve powers.

Division of Powers between Federal, State and Local: Chapters V & VI

The Australian Constitution was drafted to create a federal system of government to share power between federal and state governments.

Law-making responsibilities are divided between three levels of government: federal, state and territories, and local government. Each level has different roles and responsibilities exclusive to their requirements. However, joint responsibilities are shared in some areas, with support from federal government assistance.

The Constitution provides a mechanism for resolving any dispute regarding areas that may overlap.

There are express provisions in the Constitution for managing and resolving disputes which can arise between the Commonwealth, state and territory, or local governments regarding areas of responsibility, such as Health and Education. Specifically, while the Constitution guarantees the continued existence of the states and territories and preserves each of their constitutions and law-making powers, Section 109 provides that they are ultimately bound by the Constitution and their constitutions must be read subject to the Commonwealth Constitution. This means, that in the event of a state or territory law being inconsistent with a federal law, the Commonwealth law will override any other law.

Furthermore, if a disagreement arises between the federal and a state or Territory government regarding the division or separation of powers, the High Court of Australia is empowered to resolve disputes.

CASENOTE: Williams v Commonwealth of Australia [2010]

Commonwealth funding of Chaplaincy Programs: Case note that considers the Williams case and whether there are limits on the extent to which the Commonwealth can take over and direct operations over which the states, not the Commonwealth have power.

CASENOTE: s92 and State Border Closures

Although section 92 sounds like there can be no restrictions put on movement between the States, the High Court has ruled there are some limits to this. Click here to read more.

Human Rights under the Constitution

The Constitution does not expressly guarantee many rights or freedoms. Rather, it puts faith in the process of democracy.

In comparing the United States and Australian Constitutions, Sir Owen Dixon, a former Chief Justice of Australia attributed the omission of a Bill of Rights to a readiness on the part of the framers of the Constitution to leave the protection of rights to the legislature and the processes of responsible government. Australia’s system of human rights protection has evolved according to its own unique history alongside the international human rights system. Central to the Australian system of government is the idea that the rights and freedoms which underpin Australia’s democracy should not be taken for granted. Everyone has the responsibility to respect the human rights of others and ensure these rights and freedoms are protected and promoted.

The Australian Constitution has a small handful of express protections regarding human rights contained within it. These include:

- Acquisition of property, which must be ‘on just terms’ (section 51(xxxi));

- Trial by jury in relation to indictable Commonwealth offences (section 80;

- Freedom to exercise any religion (section 116);

- Freedom of trade between the states (section 92);

- Non-discrimination on grounds of residence in a state or territory (section 117).

‘Australians believe in peace, respect, freedom and equality. An important part of being Australian is respecting other people’s differences and choices … it is about treating people fairly and giving all Australians equal opportunities and freedoms’ Australian Home Affairs Office

Ultimately, the High Court of Australia has the final say on the protection of human rights, based on an interpretation of the Australian Constitution.

CASENOTE: Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Wills (1992) and Implied Freedom of Political Communication

The Australian Constitution (“the Constitution”) does not explicitly mention the phrase “freedom of speech” anywhere, however the High Court in Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Wills (1992) 177 CLR 1 and Australian Capital Television v Commonwealth (ACTV) (1992) 177 CLR 106 decided that the Constitution contained an implied right to freedom of communication on political matters.

CASENOTE: Case S10/2020: LibertyWorks Inc v. Commonwealth of Australia

Libertyworks Inc sought a declaration from the High Court of Australia that the registration provisions under the Foreign Interference Transparency Scheme Act 2018 (Cth)(FITS Act) were beyond the power of the Commonwealth Parliament to enact because they contravened the implied constitutional freedom of political communication.

EXPLAINER: Principle of Legality

The Principle of Legality is a common law presumption that seeks to protect citizens from arbitrary power. It presumes that Parliament does not intend to interfere with fundamental common law rights, immunities and freedoms. Click here to learn more.

VIDEO: Unstated Assumptions and Rights in the Constitution

Walter Sofronoff KC, previously Solicitor-General of Queensland and President of the Queensland Court of Appeal, looks at how Australia’s Constitution and its unstated assumptions protect our human rights and hold our government accountable.

Mr Sofronoff KC examines one of the more well-known unstated assumptions (or implied freedoms) established in Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) (1997) 189 CLR 520. The unstated assumption of the implied freedom of political communication is not specifically written in the Constitution, but provisions such as the Parliaments of Australia should be elected by the Australian people, imply there is a freedom for the Australian people to know and be aware of the Government, and its ministers, and the most common way for this to occur is through a free press. Click here to see the Video on Youtube

“The strength of our constitutional arrangement lies not just in the very boring, technical language of our constitution, which says nothing about rights, but in the unstated assumptions of the law that the judges understand and apply when they have to, and that the people of Australia understand and believe in”

– Walter Sofronoff KC

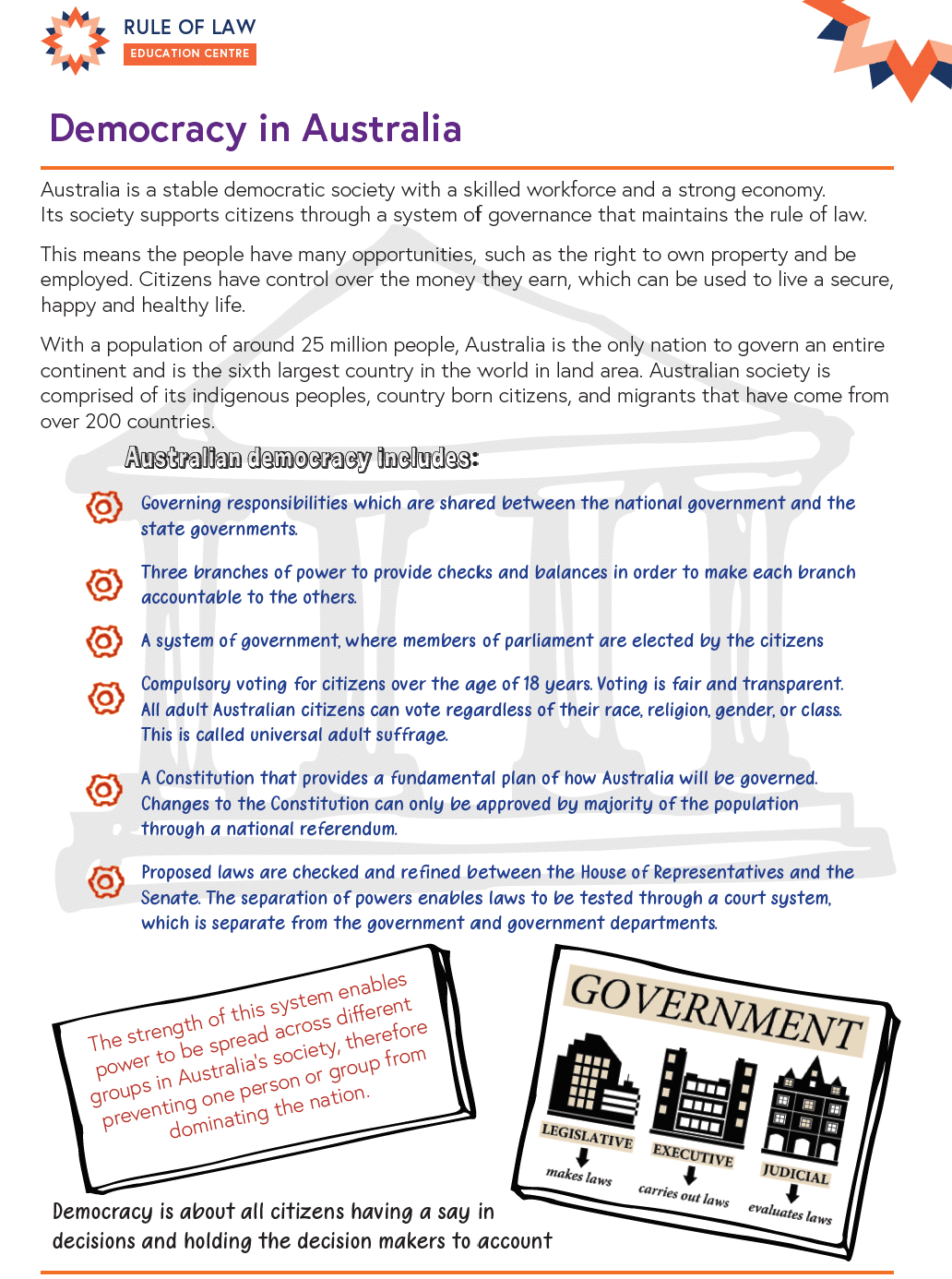

Representative Government

Sections 7 and 24 of the Constitution requires both houses of Federal Parliament to be ‘directly chosen by the people’. The power of government was to come from the Australian people by delegating the task of government to chosen representatives. An example of this can be found in sections 7 and 28 of the Constitution – elections for the House of Representatives and the Senate will be regular to ensure that representatives remain accountable to the people for thier decisions.

Outlined in Sections 8 and 30, fair and even representation for elections included ‘each elector shall vote only once’ and eligibility is open to all citizens where elected representatives will be paid for their service.

Elected representatives appear in Parliament and carry out a number of responsibilities including:

- Making representations on behalf of their constituents to Parliament;

- Debating issues and ensuring elected representatives remain accountable and subject to public scrutiny;

- Making laws;

- Monitoring the expenditure of public money.

Responsible Government

A responsible government is an idea based on the Westminster system, where the Executive government of the day is drawn from the political party that commands a majority of votes in the House of Representatives and is accountable to the Parliament.

The Australian Constitution relies on long established conventions and practices that support the formal operation of government. It does not specifically mention the role of the Prime Minister or Cabinet, even though this is where the executive power of the federal government lies. Under the Westminster system, responsible government implies that as long as the Prime Minister continues to have the support and confidence of the majority of the Parliament, they can keep their job. The Crown has pervasive influence in the day to day running of our nation; however, it does not play a vital role in the operation of the federal government. Instead, the role is mostly ceremonial. Section I of the Constitution gives the strong impression that the Crown oversees the operations of Federal Parliament, when in fact, it is the Governor-General who exercises the executive power of the Queen as her representative (see Section 61).

Prime Minister

The head of the Australian government and the elected leader of the party in government. By convention, the Prime Minister is a member of the House of Representatives and leads the nation with the support of the majority of the members.

Cabinet

Made up of senior Ministers who are presided over by the Prime Minister, the Cabinet is the foremost policy making body for the government. Ministers are selected to serve on the Cabinet by the Prime Minister.

Governor General

Appointed by the Queen on the advice of the Australian Prime Minister. The Governor-General is a member of the Executive and exercises power and acts in accordance with the conventions of responsible government.