The Youth Koori Court

Specialist Courts

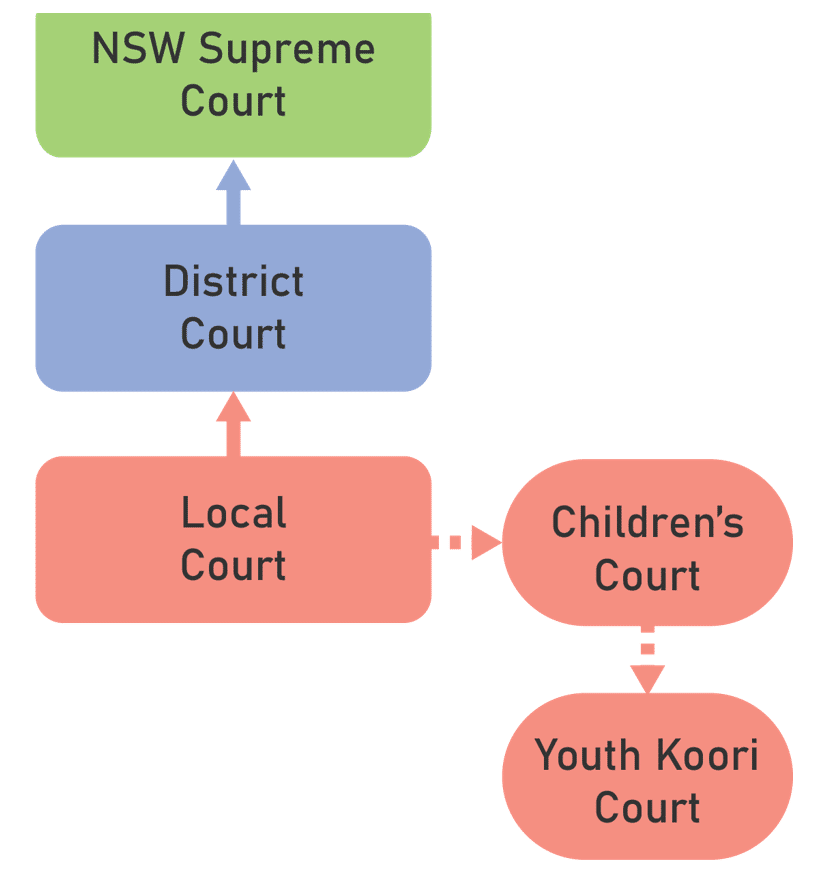

Along with the Coroners Court, the Drug Court and the Children’s Court, the Youth Koori Court is a specialist court that sits at the Local Court level in the NSW court hierarchy. For more information on court hierarchies, view our resources here.

What is the Youth Koori Court?

The Youth Koori Court (YKC) is a specialised, diversionary court within the Children’s Court of NSW. The YKC program has been designed to address the disproportionate level of young Indigenous Australian criminal offenders in the long term. It was developed as a pilot project in 2015 at Parramatta Children’s Court as an alternative to sentencing young Indigenous people to juvenile detention centres. After its initial success, the NSW Children’s Court was granted funding to establish branches in other locations, expanding to Surry Hills Children’s Court in 2019 and Dubbo Children’s Court in March 2023.

The YKC is not a legislated court, meaning that it does not have its own governing legislation like the Children’s, Drug and Coroners Courts, and, as a result, does not have separate funding provided by the NSW government. Established by the Children’s Court of NSW Practice Note 11, it aims to provide a more culturally sensitive approach to dealing with criminal offences committed by young Indigenous Australians.

The YKC is a form of restorative justice, which is focussed on repairing harm and addressing the needs of all parties involved, including victims, offenders, and the community, rather than simply punishing offenders. Through this process, offenders take responsibility for their actions and work to make amends.

Being a branch of the Children’s Court, the YKC’s jurisdiction, policies, rules and procedures are the same as those of the Children’s Court.

The YKC is not a legislated court, meaning that it does not have its own governing legislation like the Children’s, Drug and Coroners Courts, and, as a result, does not have separate funding provided by the NSW government. Established by the Children’s Court of NSW Practice Note 11, it aims to provide a more culturally sensitive approach to dealing with criminal offences committed by young Indigenous Australians.

The YKC is a form of restorative justice, which is focussed on repairing harm and addressing the needs of all parties involved, including victims, offenders, and the community, rather than simply punishing offenders. Through this process, offenders take responsibility for their actions and work to make amends.

Being a branch of the Children’s Court, the YKC’s jurisdiction, policies, rules and procedures are the same as those of the Children’s Court.

What are the aims of the Youth Koori Court?

The NSW Children’s Court Practice Note 11: Youth Koori Court sets out the five aims of the YKC program, which are to:

- Increase Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people’s, confidence in the criminal justice system

- reduce the risk factors related to the re-offending of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people

- reduce the rate of non-appearances by young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders in the court process

- reduce the rate of breaches of bail by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people, and

- increase compliance with court orders by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people.

How does the YKC work?

The court operates using a circle sentencing model involving the participation of the young offender and their support persons, Indigenous elders or respected persons, community representatives, caseworkers and a YKC magistrate.

Sentencing circles create a more informal and collaborative process, where the offender is encouraged to take responsibility for their actions and perform steps to re-integrate themselves into their community. In addition, the YKC also provides support services to help address underlying issues that may have contributed to the offending behaviour, such as substance abuse, mental health issues, and family and social problems.

Eligibility and Referral

Practice Note 11 specifies eligibility for the YKC program in NSW. The criteria are that the young person:

- must have entered a plea of guilty, indicated they will enter a plea of guilty, or had an offence proven (been found guilty) after a hearing

- must be descended from an Aboriginal person or Torres Strait Islander, identify as an Aboriginal person or Torres Strait Islander and be accepted as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander by the relevant community

- be charged with an offence that will be finalised by the Children’s Court

- be likely to receive a sentence that is either a community-based order with Youth Justice supervision or a control order e. be 10 to 17 years of age at the time of the commission of the offence(s) and under 19 years of age when proceedings commenced

- be willing to participate.

- In addition, they must not have committed a crime of a sexual nature.

Once a young Indigenous offender has signalled an intention to plead guilty or has pled guilty, they may apply to participate in the YKC program. If they have been found guilty in the Children’s Court, they may apply, or the presiding judicial officer may refer them. A sentence is not imposed on the young person prior to commencing the program.

A Koori Court Casework Co-ordinator will then meet with the offender to assess eligibility and suitability for the program. If they are deemed unsuitable, they will be referred back to the judicial officer who presided over their matter for sentencing in the Children’s Court.

Procedure

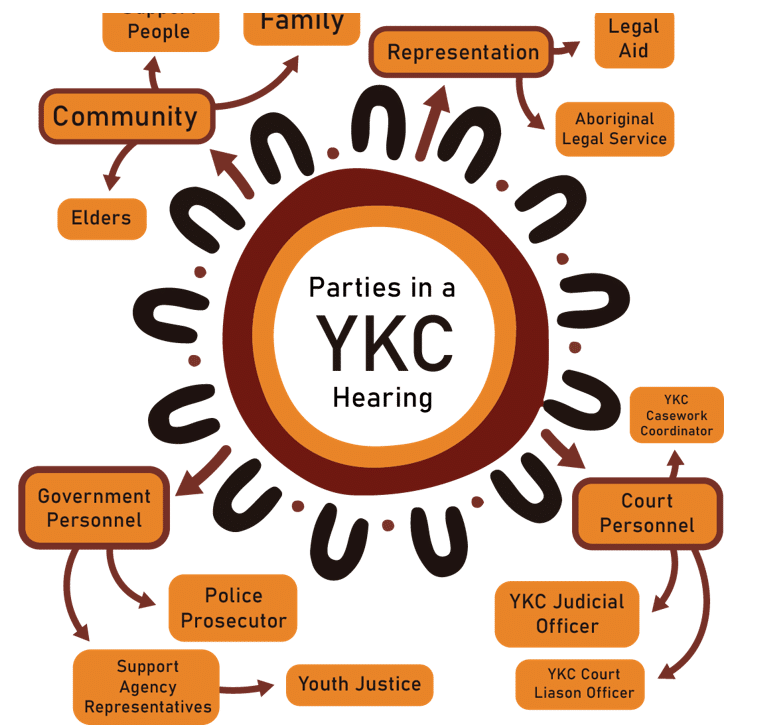

Once deemed able to participate, the offender will be scheduled for a YKC conference. These conferences are conducted in court and are on record. They typically involve the presence of:

- the offenders’ family members and support people

- legal representation for the young person from the Aboriginal Legal Service

- in more complex cases, a representative from the Children’s Civil Law Service (a part of Legal Aid)

- government and non-government support agency representatives (such as Department of Education and Justice, Health, Family and Community Services)

- YKC casework co-ordinator

- at least one Indigenous elder or respected person

- a representative from Youth Justice

- a Police Prosecutor

- the YKC Court Liaison Officer

- the YKC judicial officer.

Collectively, these members of the offender’s community will communicate openly with the offender and each other to develop an Action and Support Plan (ASP). The ASP might set out ways for the offender to:

- improve their cultural connections,

- stay at school or get work,

- have stable accommodation and

- address any health, drug or alcohol issues.

The focus of the court is not on the offence until after they have completed the program, when a sentencing decision is made.

The ASP must be approved by the magistrate overseeing the offender’s case before it can commence. It may be up to 6 months in duration, during which time the offender must report to court regularly for the magistrate to check their progress.

The YKC may opt to discharge offenders from the program if it is satisfied that they have not complied with their ASP or for any other reason. The young person may also choose to withdraw their consent to participate at any time.

If the ASP is completed successfully, the YKC will invite the offender to attend a graduation ceremony to commend them on their achievement. The offender’s YKC casework co-ordinators will write a report on the offender’s rehabilitation and hand it to the court. The magistrate will then assess the report and based on the offender’s participation, decide on a sentence for their initial charge.

If the offender complied well with their ASP, their sentence may be reduced (compared what they may have received without the program). If they complied exceptionally well, it may be dismissed entirely. If the offender showed little or no effort in complying with their ASP, their sentence may be reduced by only a small margin, or potentially not at all.

Rule of Law Principles

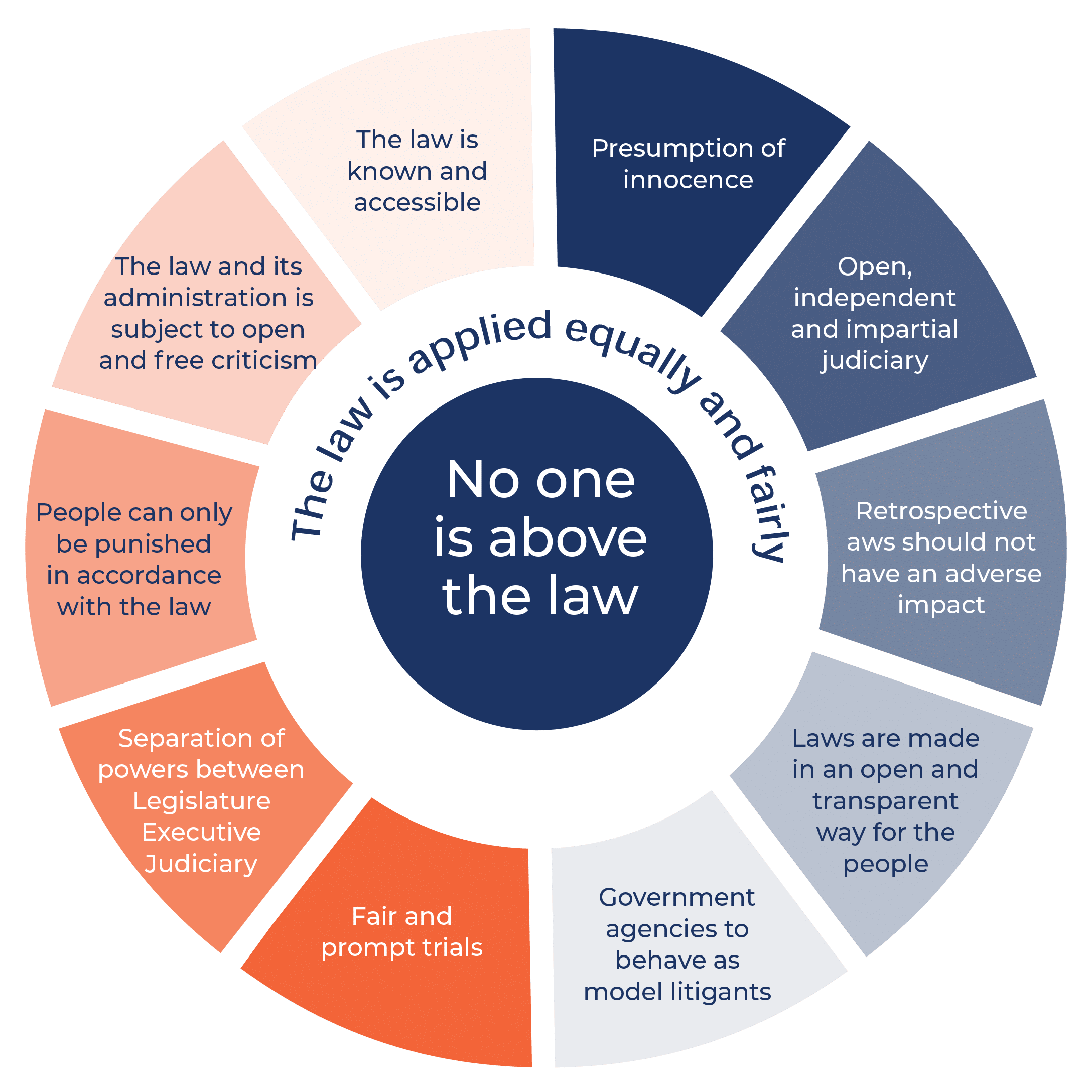

The YKC’s incorporation of Indigenous culture and community involvement into its processes contributes to improved access to justice and fairness for young Indigenous offenders.

Access to justice

The YKC seeks to improve access to justice for Indigenous young people by providing a culturally sensitive and inclusive environment. It acknowledges the unique cultural and historical context of Indigenous Australians, and takes into account, among other factors, their language, customs, and traditions. This may help to engage young Indigenous people with the justice system in a way that is more suitable for their needs and improve the chances of success.

YKC conferences illustrate this by including members of the offenders’ community to help with their guidance and rehabilitation using a cultural perspective. Moreover, the unique ASP is developed collaboratively and designed to accounting for the offender’s specific circumstances and struggles, assisting in achieving a just outcome. In addition, the Aboriginal Legal Service (ALS) will also be available to these young offenders to provide free legal representation, accommodating for those who may not be able to access private legal representation.

Fairness and equality before the law

While it might seem as if the YKC grants ‘special treatment’ towards an exclusive group of people and is therefore unfair, granting additional support to the most disadvantaged and over-represented category of young offenders is an important step towards counteracting social imbalances and achieving equality.

Young offenders from other backgrounds who also suffer from social disadvantage or discrimination (such as those suffering from mental illnesses, poverty, or traumatic upbringings) may not be admitted to the YKC, but their circumstances will be addressed by judicial discretion in the Children’s Court. These measures all contribute to the courts’ aim to achieve fair outcomes for offenders by recognising disadvantages rather than ignoring them.

Assessing Effectiveness: Statistics and Case Studies Statistics

A report published in 2022 by the Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research found that the YKC had significant effect on lowering re-offending rates of young Aboriginal offenders. Compared to matters finalised through the mainstream Children’s Court processes, the YKC had an estimated “40% reduction in the probability of being sentenced to a JCO (Juvenile Control Order)”.

However, the report also comments that while overall results are positive, YKC programs require a large amount of resources. Casework co-ordinators, support workers and magistrates must commit to months-long assignments overseeing a young offender.

Case: R v Nerri [2022] NSWChC 2

This case illustrates an example of the YKC program working effectively to rehabilitate a young offender. Nerri, a 13-year-old Kamilaroi and Yuin girl had an extensive criminal history with over 40 charges, many of which were committed while on bail. She 18 separate breach offences stemming mostly from Good Behaviour Bonds, and had 21 admissions to youth detention.

Nerri was admitted to the YKC on August 9, 2019, after being charged with numerous serious criminal offences, including stealing a car and reckless driving. The YKC developed an Action and Support Plan with the aim of reducing personal risk factors related to her re-offending. She appeared before the YKC on August 16, 2019. The parties that committed to her ASP were:

- Aunty Susan Darum

- Jarara Indigenous Education Support

- Justice Health

- Women’s Justice Network

- Youth Justice

- Legal Aid NSW – Children’s Civil Law Service

She complied with her Action and Support Plan, undergoing 17 reviews. By the end of the ASP, Nerri had ceased her criminal behaviour and achieved significant personal growth, including advocating on social justice issues, volunteering with community initiatives, and assisting other young offenders in their path to social re-integration. Nerri graduated from her YKC program with such success that the sentences imposed on her for her initial offences were dismissed entirely.

Koori Courts Across Australia

Queensland

Queensland has a specialised community sentencing court called the Murri Court, which was established in 2002 to reduce the overrepresentation of Indigenous people in prisons. Once an offender is referred to the Murri Court, arrangements are made for the offender to engage with support services, including counselling, addiction treatments and education. After some time (typically around three months), the offender will attend a Murri Court conference, in which the offender’s support workers will report on their progress and the magistrate will form a sentence with these considerations.

Victoria

In Victoria the Children’s Koori Court is regulated by s 514 of the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (Vic). The Victorian Koori Courts differ from those of NSW, as they have Koori Courts for both children and adults and do not impose an Action and Support Plan. However, they may impose community-based programs instead, requiring offenders to regularly report to the magistrate and Elders.

South Australia

The Nunga Court of South Australia does not function as diversionary program for Indigenous offenders, rather, it gives the offender an opportunity to be heard by an Indigenous Elder of their locality, who is able to advise the sentencing magistrate. The aim of the Nunga Court process is to gather information about the defendant that may provide the cultural context needed to consider relevant sentencing factors appropriately.

Common Features

Though there are some differences in how they operate, all of these specialist courts are sentencing courts, which deal only with defendants who have pleaded guilty. The commonly used ‘circle sentencing’ model of using informal conferences which are heard before Indigenous Elders and draws upon the communal philosophies of many Indigenous cultures around Australia. Moreover, the inclusion of Indigenous people within the judicial process allows for a deeper understanding and recognition of the social, cultural and personal issues an Indigenous offender may be experiencing.