Using the Case Method in History to teach civics concepts

“The results [of the Case Method Project] have been incredibly positive, especially in terms of strengthening students’ critical thinking, their retention and understanding of course material, and their civic interest and engagement”

– David Moss, Professor at Harvard Business School

Using the Case Method within the Australian historical context to teach students about democratic and legal principles that underpin our democracy.

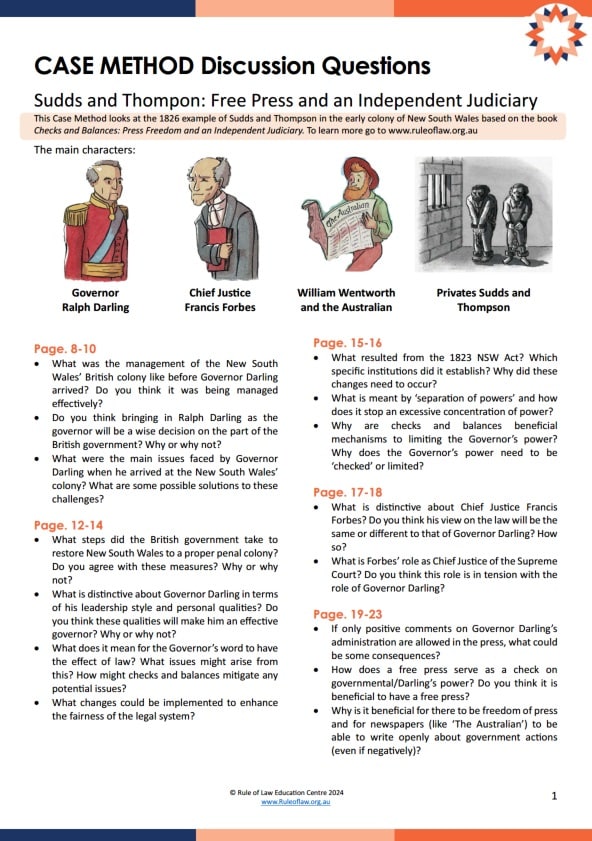

1. Sudds and Thompson 1826: Highlighting the importance of a Free Press and Independent Judiciary following the conflict between Governor Darling and Chief Judge Francis Forbes after the death of Private Sudds and Thompson. Click here to learn more.

The “Case Method”, originally developed by Harvard Business School (and later adapted by Professor David Moss for use in the high-school history classroom), is an innovative teaching approach that utilises decision-forcing cases to immerse students in real historical dilemmas from the past. The approach fosters critical thinking and facilitates student engagement in civil debate. It further provides historical distance – enabling students to safely practice political conversation without politicising the classroom.

By consulting pertinent primary source readings, students formulate their own opinions about the past, then actively contribute to in-class discussions guided by teacher questions. Primary sources mirror the information available to decision-makers at the time, encouraging empathy and a deeper appreciation of historical complexities.

The cases are taught in the present tense, wherein the story progressively unfolds, and students deepen their knowledge through set-readings. By placing students in decision-making roles and withholding actual outcomes, the “Case Method” engages problem-solving skills as students work through complicated historical problems and process contending points of view. Students engage in civil discussion with their classmates to develop a collective solution.

The active participation of students in class discussion further makes the content memorable, and as such, students will be able to draw connections between in-class content and modern-day legal issues that they face now and in future.

How is it done?

- Firstly, access a case (for example, the founding of the NSW Supreme Court or the Kables Case: The First Civil Case in NSW). This case can form the basis of class discussion, for example, for three lessons.

- Students are provided with primary source documents / ‘Exhibits’ (readings of around 4-5 pages) in advance. Students complete the reading before class and come prepared to discuss the case in depth during class.

- Class time is then used as discussion – where students have an opportunity to think critically, problem-solve and constructively build upon or disagree with their classmate’s comments.

- In the first lesson on a new case, teachers set the scene for the class by orientating students to the historical context, key issues and personalities. This is done in the present tense, for example, “Imagine: You are Chief Justice Forbes…” and the story is to gradually unfold.

- Students then locate evidence by referring to the source document (known as an ‘Exhibit’) they read prior to class. This will contain pertinent information, quotes and statistics etc. Exhibits reflects the information available to decision-makers at the time, allowing students to consider what they would have done if they were key figures from the past – like Governor Darling.

- Throughout, the teacher prompts discussion with questions, for example, “What was the management of the New South Wales’ British colony like before Governor Darling arrived? Do you think it was being managed effectively?”

- As the class discusses, the teacher notes student input up on the board – i.e potential solutions to the issues Governor Darling faced when he arrived to the New South Wales’ colony.

- Importantly, each case builds to a particular decision point – for example, “Should we have a separation of powers in Australia?” – without revealing what decision was actually made. This allows students to think critically and refine their opinions as the story unfolds.

- At the very end, the teacher reveals the outcome – what actually occurred and why.

Documents Needed

- Cases (based on history) without a stated outcome, which let the story unfold/teach history in the present. (And a separate document with the outcome, for the teacher to reveal this at the end: reveals what actually occurred and why).

I.e. “Imagine: You just fought in the American Revolution” – can use a narrative voice that directly imbeds students into the class (character, narrative, tension: tell it as a story —> adds urgency). - Contextual orientation – for teachers to set the scene for the class.

- Primary source documents (can be longer: 4-5 pages up to 9) for students to engage with that provide an insight into the information available to decision-makers at the time. These will be hand-outs that students read prior to class. Label as ‘Exhibits’ i.e. ‘Exhibit 4’ (ideally, they reveal a specific facet of the topic – i.e. newspaper articles or case summaries).

- Worksheets, assignment questions and teaching plans.

- Teachers record information on whiteboards.

- Discussion questions (that the teacher can use to prompt class discussion)