Approaches to the Rule of Law

The rule of law is a complex concept that has been debated and analysed by scholars for centuries. At its core, the rule of law is concerned with the fairness, accessibility, and efficiency of the legal system, from the creation of laws, through their enforcement, and finally to the court process.

The rule of law is a complex concept that has been debated and analysed by scholars for centuries. At its core, the rule of law is concerned with the fairness, accessibility, and efficiency of the legal system, from the creation of laws, through their enforcement, and finally to the court process.

It encompasses concerns about equality under the law, government accountability, constraints on arbitrary power, independent and impartial dispute resolution, protection of human rights, democratic involvement in law-making, and a broader culture of lawfulness.

This section explores four different approaches to the rule of law:

- A. V. Dicey, a famous nineteenth-century English legal theorist;

- Lord Bingham, a senior British judge who died in 2010;

- Professor Martin Krygier, an Australian legal theorist;

- Rule of Law Education Centre Rule of Law Wheel

There are also many other lawyers and scholars who also discuss the rule of law, including Joseph Raz, Lon Fuller, F. A. Hayek, Philip Selznick, Brian Tamanaha, Geoffrey de Q. Walker, and James Spigelman.

A.V Dicey

Albert Venn Dicey was a nineteenth-century English legal theorist. He is the most famous rule of law theorist, although his interpretation of the concept has been criticised.

Dicey argued that England displayed the rule of law in three ways:

-

- “That no man is punishable, or can be lawfully made to suffer in body or goods, except for a distinct breach of law established in the ordinary legal manner before the ordinary Courts of the land. In this sense, the rule of law is contrasted with every system of government based on the exercise by persons in authority of wide, arbitrary, or discretionary powers of constraint;”

- “Not only that with us no man is above the law, but (what is a different thing) that here every man, whatever be his rank or condition, is subject to the ordinary law of the realm and amenable to the jurisdiction of the ordinary tribunals;” and

- “That the general principles of the constitution (as, for example, the right to personal liberty, or the right of public meeting) are with us the result of judicial decisions determining the rights of private persons in particular cases brought before the Courts; whereas, under many foreign constitutions, the security (such as it is) given to the rights of individuals results, or appears to result, from the general principles of the constitution.”

Dicey’s interpretation of the rule of law has long been criticised as focusing too much on England, to the exclusion of other countries. It is no longer true, say his critics, if indeed it ever was, that England is the only country governed by the rule of law. The rest of the Western world, such as Continental Europe and the United States, not to mention non-Western countries, cannot have the rule of law, according to Dicey’s interpretation, simply because they are not English. Therefore, his interpretation is flawed.

Nevertheless, it highlights some key principles that have remained important throughout later discussions of the rule of law: a distrust of arbitrary power, and an insistence on equality before the law.

Although flawed, Dicey’s account of the rule of law in England shaped future generations of lawyers and scholars, and raised some key principles that are still held to be important today.

Lord Bingham

Lord Tom Bingham was a British judge who died in 2010. He was Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, and Master of the Rolls, and Senior Law Lord. He published a book called The Rule of Law in 2010, which sets out eight principles that Lord Bingham considered made up the rule of law:

-

- “The law must be accessible and, so far as possible, intelligible, clear, and predictable”;

- “Questions of legal right and liability should ordinarily be resolved by application of the law, and not the exercise of discretion”;

- “The laws of the land should apply equally to all, save to the extent that objective differences justify differentiation”;

- “Legal protection of such human rights as, within that society, are seen as fundamental”;

- “Means must be provided for resolving, without prohibitive cost or inordinate delay, bona fide civil disputes which the parties themselves are unable to resolve”;

- “Ministers and public officers at all levels must exercise the powers conferred on them reasonably, in good faith, for the purpose for which the powers were conferred, and without exceeding the limits of such powers”;

- “The adjudicative procedures provided by the state should be fair”; and

- “Compliance by the state with its obligations in international law.”

Bingham’s approach is more helpful than Dicey’s in many ways, drawing attention to the principles that countries around the world might aspire to, regardless of their history or arrangement of government institutions. There is nothing specifically English about his definition of the rule of law.

Nevertheless, Bingham’s broad definition is also controversial, particularly in its inclusion of human rights protections, and compliance with international law. Critics have argued that it reads more like a shopping list of ideal characteristics of a country or government, rather than an explanation of the rule of law. This, they say, robs the concept of ‘the rule of law’ of any meaningful content; it just becomes a list of things we think are good for a government to do.

Profesor Martin Krygier

Professor Martin Krygier, a former member of the governing committee of the Rule of Law Institute, is an Australian legal theorist. He is currently the Gordon Samuels Professor Law and Social Theory at the University of New South Wales, in Sydney.

Krygier’s interpretation of the rule of law differs from many other scholars in his insistence that we should not list principles or institutions that we regard as indispensable to the rule of law, but rather first ask why we value the rule of law – what is the purpose of it – and then proceed to identify the institutions and legal mechanisms that will advance that purpose.

Krygier argues that the purpose of the rule of law is “to temper or moderate the exercise of power, in order to avoid its arbitrary use”. Therefore, institutions or mechanisms that advance this purpose in a particular society or point in time are what we mean by the rule of law.

In a lecture to the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation in October 2024, Krygier said “The rule of law is a device to try to deal with a particular mischief, which is very persuasive and that is arbitrary power. What it seeks to do .. is to temper the exercise of power.”

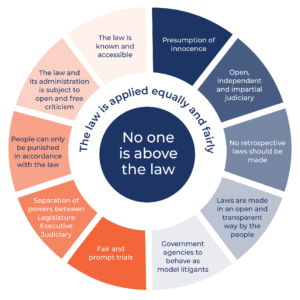

Rule of Law Education Centre

Central to the wheel and the rule of law is the concept that no one is above the law – it is applied equally and fairly to both the government and citizens. This means that all people, regardless of their status, race, culture, religion, or any other attribute, should be ruled equally by just laws.

Beyond this, the outer edge of the wheel illustrates the number of inter-related principles that uphold the rule of law in Australia, such as the presumption of innocence, and fair and prompt trials. These principles can be considered essential elements that contribute to maintaining the rule of law. Without these, the wheel would fail to turn and Australia’s rule of law would not continue to be upheld and maintained.

The final essential element is that these principles and Australia’s rule of law is supported by informed and active citizens. Without responsible and engaged citizens, society is unable to work together to uphold important principles and values which support our rule of law and democratic society.

Below is an interactive wheel, where further details on each principles can be accessed by clicking on the different sections.