The Principle of Legality

What is the Principle of Legality?

The Principle of Legality is a common law presumption that seeks to protect citizens from arbitrary power. It presumes that Parliament does not intend to interfere with fundamental common law rights, immunities and freedoms. The judiciary uses the Principle of Legality to safeguard such rights when an ambiguity emerges in statutory interpretation. This presumption stems from the principle of parliamentary sovereignty and the understanding that Parliament is taken to create legislation with common law principles in mind. The Principle of Legality, thus, operates as a check and balance on its power.

Although, Heydon J, in the High Court decision of Momcilovic v The Queen (2011) 245 CLR 1, provided a lengthy list of ‘fundamental rights,’ this list is not exhaustive. Rather, given that the Principle of Legality is rooted in the Common Law, it means that the scope of ‘fundamental rights’ necessarily remains open to judicial discretion.

The rationale for the principle was first set out in Australia by O’Connor J in the High Court decision of Potter v Minahan [1908] HCA 63:

“It is in the last degree improbable that the legislature would overthrow fundamental principles, infringe rights, or depart from the general system of law, without expressing its intention with irresistible clearness…”

In other words, the rationale behind the Principle of Legality relies on an assumption that, within a democracy like Australia, the legislature would not intend, by statute, to modify or abolish fundamental rights, unless they have made this intention explicitly known by clear and unambiguous statutory language.

Application of the Principle of Legality in Australia.

In practice, the Principle of Legality is applied by the judiciary in the interpretation of statutes. However, as above, its operation is subject to judicial discretion and, therefore, is not fixed in nature – particularly when considering what rights are fundamental.

In accordance with the ordinary principles of statutory interpretation, the courts seek to ascertain the ordinary and literal meaning of the words. If no ambiguity is found in the meaning of the words, or where there is only one clear meaning, then the courts will consider that meaning to be representative of the true legislative intent. However, where there is ambiguity in the meaning of the words of a statute, or where there is more than one possible interpretation, then the Principle of Legality will be applied. Consequently, the courts will generally choose the interpretation which avoids or mitigates any abrogation or curtailment of rights. In other words, the Principle of Legality operates to resolve the ambiguity in favour of protecting fundamental common law rights, freedoms and immunities.

An example of where the Principle of Legality was applied was in North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency Limited v Northern Territory (2015) 326 ALR 16. This case was related to the popularly dubbed ‘paperless arrest’ regime. Under this regime, police were enabled by statute to arrest and detain a person for certain minor offences for up to 4 hours without a warrant. The question concerning statutory interpretation in the proceedings was:

(1) As the plaintiffs argued, whether police had the authority to detain a person for 4 hours; or

(2) As the Northern Territory argued, whether police were required to detain a person only for a reasonable period of time up to that maximum.

A majority of the High Court held that there was an “obvious application of the principle of legality… [because] the common law does not authorise the arrest of a person or holding an arrested person in custody for the purpose of questioning or further investigation.”

When applying the ordinary meaning of the words, the court found that the common law right to liberty had not been overridden by the statute, rather, the 4-hour period was to be regarded as a maximum only. The statute lacked the sufficient explicit language needed to validate a departure from that fundamental right to liberty. Thus, the Court held in favour of the Northern Territory’s interpretation.

Rebutting the Principle of Legality

Given the doctrine of Parliamentary Sovereignty, the Principle of Legality is entirely rebuttable. Since it only comes into operation where the statutory text is ambiguous, the legislature simply needs to use unequivocally clear language. Where the statutory language gives rise to only one ‘constructional choice’ which interferes with fundamental common law rights, or several constructions which equally interfere with such rights, then the Principle of Legality is “of no avail against such language” (Momcilovic v The Queen (2011)).

The Rule of Law and the Principle of Legality

Former Chief Justice of Australia, the Honourable Murray Gleeson AC QC was apt to cite Lord Irvine of Lairg’s description that “the fundamental common law Doctrine of Legality [represents] the kernel of the Rule of Law.” The Rule of Law and the Principle of Legality are entwined in four key ways.

First, the Principle of Legality safeguards the fundamental rights of citizens against the encroachment of government. It achieves this by empowering the judiciary to confine ambiguous evidence of legislative intent to only that which the words expressly and ordinarily reveal. It means that courts will be slow to validate the abrogation of rights.

Secondly, the Principle of Legality acts as a check and balance on the enactment of retrospective legislation. Retrospectivity alters the legal status of actions performed in the past, i.e., they are laws passed today, that change what was legal or illegal yesterday. To protect against the arbitrary enactment of retrospective laws which may abrogate fundamental rights and freedoms, the Principle of Legality requires retrospective intention to be expressed in clear and unambiguous statutory language before the courts can validate its application.

Thirdly, the Principle of Legality safeguards court accessibility. A notable example of this occurred in the High Court case of Plaintiff S157/2002 v Commonwealth [2003] HCA 2 where the court applied the principle to read down an ambiguous provision which sought to restrict the availability of writs against Commonwealth officers. Consequently, the court upheld the idea that although government agencies are to behave as model litigants, they are not above the law and thus not immune from prosecution by people whom their actions and decisions have affected.

Finally, the Principle of Legality ensures that there is consistency and coherence in the way statutes are interpreted. It ensures that like cases are treated alike and prevents the proliferation of arbitrary differences in cases based on an ambiguity in the wording. It forces parliament to take an active and intentional role in their legislative responsibilities where laws are created with the utmost clarity. Ultimately, it ensures that the law is known and accessible with citizens gaining a reinforced confidence in Australia’s system of government and the integrity of its institutions.

Threats to the Principle of Legality.

When threats to security, war, terrorism, or more general conflict arises, people look to the Government for their protection. In these situations, it is common that people become tolerant of excessive government power. Times of heightened stress on a nation can undermine the protections and safeguards afforded by the Principle of Legality. These protections are often sacrificed in pursuit of total government authority to control or quell a particular threat or conflict.

The COVID-19 Pandemic is an illustrative recent example of this phenomenon. During that period of emotional, physical and financial stress, the community was susceptible, and, in some cases did, become so hyper-focused on urging the Government to remedy the problem, that they either failed to recognise, or were indifferent to the abrogation and curtailment of their fundamental rights and freedoms.

Principle of Legality Case Study

Kassam v Hazzard; Henry v Hazzard [2021] NSWSC 1320; [2021] NSWCA 299

This case note focuses on two proceedings that were heard together (as a matter of efficiency given their similarities) in the Supreme Court of NSW and then on appeal in the NSW Court of Appeal. Analysing the proceedings, offers insight into which fundamental rights can be protected by the Principle of Legality, how Australian courts are appearing to retreat from the principle, and the implications this has for the rights and freedoms of citizens.

Facts

In June 2021, the Delta variant was first detected in NSW, and resulted in a sudden list of orders under the Public Health Act 2010 (the PHA) which attempted to curb infection levels and safeguard public health. The key focus of these two proceedings are the aspects of the orders which prevent some individuals from working in aged care, education, and construction sectors, and prevent authorised workers from leaving an affected area of concern.

The Kassam Plaintiffs

One of the proceedings was brought by Mr Al-Munir Kassam, a construction worker, and 3 other plaintiffs (together, the Kassam Plaintiffs). The Kassam Plaintiffs sought to sue the Minister for Health, the Chief Medical Officer, the State of NSW and the Commonwealth of Australia. They argued that Order No. 2 of the Public Health (COVID-19 Additional Restrictions for Delta Outbreak) Order (Order No. 2) and S 7 of the PHA were invalid.

The Henry Plaintiffs

The other proceeding was brought by Ms Natasha Henry, an aged-care worker, and five other plaintiffs who were also from the health, education, construction and aged care sectors (together, the “Henry Plaintiffs”). The Henry Plaintiffs sought to sue the Minister only and sought declarations that Order No 2 was invalid along with the Public Health (COVID-19 Aged Care Facilities) Order 2021 (NSW) (the Aged Care Order) and the Public Health (COVID-19 Vaccination of Education and Care Workers) Order 2021 (NSW) (the Education Order; and collectively the impugned orders).

In effect, both the Kassam and Henry Plaintiffs sought a declaration invalidating the public health orders that required mandatory vaccination for workers in certain industries. It is important to note that the public health orders in question, did not force workers in the above industries to get vaccinated. The public health orders only required that if an individual wanted to continue working, or gain employment, in the above industries, then they had to be vaccinated. Failure to comply with these public health orders (i.e., failure to get vaccinated) meant that these individuals could no longer work or gain employment in these industries.

Procedural History

At first instance, the proceedings were heard in the Supreme Court of NSW. The hearing commenced on 30 September 2021 and concluded on 6 October 2021, before the orders were handed down on 15 October 2021. The presiding judge dismissed both proceedings.

The Kassam and Henry Plaintiffs appealed against the decision to the NSW Court of Appeal. The appeal was heard before Bell P, and Meagher and Leeming JJA. Judgement was handed down on 8 December 2021. Whilst their Honours refused leave in respect of various grounds of appeal and granted leave in respect of other grounds, they ultimately dismissed the appeal. The Kassam and Henry Plaintiffs were ordered to pay the costs of the application for leave to appeal and for the appeal.

The Principle of Legality Argument

A fundamental ground of challenge in both proceedings concerned the effect of the orders on the rights of voluntarily unvaccinated individuals. The Kassam and Henry Plaintiffs sought to deploy the Principle of Legality to argue that, as an issue of interpretation, the broad words of S 7 (PHA), cannot authorise the interference with those rights. They also alternatively tried to argue that the orders were otherwise unreasonable given their effect on the rights of such individuals. In other words, it was argued that the impugned orders violated several fundamental freedoms that extend beyond a mere temporary curtailment of the right to liberty and freedom of movement and had not been abrogated by clear, unambiguous statutory language (at 193).

However, Beech-Jones CJ at CL noted that “the presumption is of little assistance in construing a statutory scheme when abrogation is the very thing which the legislation sets out to achieve” [8]. Here, his Honour highlights the idea that, where legislation unambiguously purports to abrogate fundamental rights or freedoms, that legislation cannot be struck down by reference to the Principle of Legality. Given the legislative intention in this case was unambiguously clear, the judiciary must deem the law to be valid. It therefore follows that the Principle of Legality only comes into play when the language of the legislation is ambiguous and operates to resolve the ambiguity in favour of protecting fundamental rights and freedoms.

The Plaintiffs also attempted to argue that the “impugned orders interfere with a person’s right to bodily integrity and a host of other freedoms” [9], again relying on the Principle of Legality to advance their argument. However, Beech-Jones CJ at CL opined that, when the impugned orders are accurately examined, they do not violate an individual’s right to bodily integrity since the legislation does not “authorise the involuntary vaccination of anyone” [9]. Rather, the impugned orders curtail the free movement of persons which is the “very type of restrictions that the PHA clearly authorises” [9]. As such, the Principle of Legality did not justify the reading down of s 7(2) of the PHA to preclude the imposition of limitations on that freedom

Beech-Jones CJ at CL commented that “it is to the common law that recourse must be had” [197] when identifying the fundamental rights and freedoms which may be protected by the principle of legality, rather than to international treaties or federal legislation.

Outcome

All other grounds were rejected, and both proceedings were dismissed.

On appeal in the NSW Court of Appeal

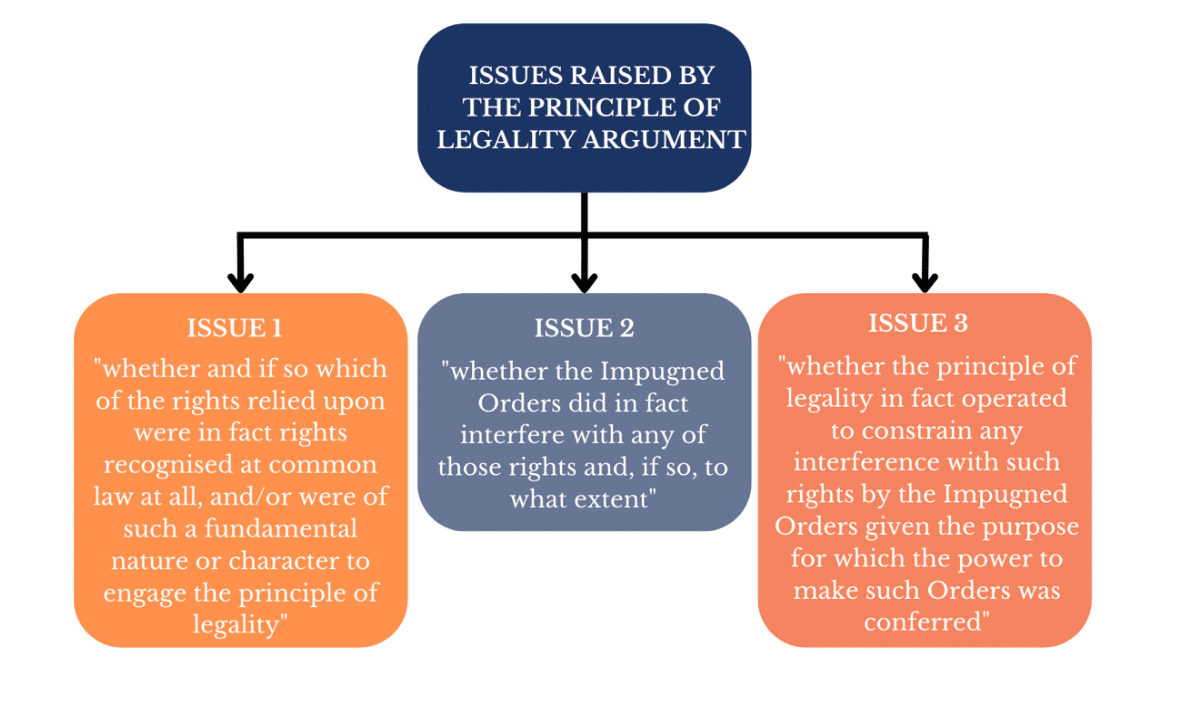

The Kassam Applicants raised 11 grounds of appeal, and the Henry Applicants raised 8 grounds of appeal. Since this case note focuses on the Principle of Legality, concentration will be on the Applicants’ particular argument based upon this principle. As outlined by Bell P, and Meagher and Leeming JA at [92], the Applicants’ Principle of Legality argument raised 3 issued:

The Principle of Legality in General Terms

Their Honours made some general comments about the Principle of Legality, before closely examining the Applicants’ argument and the above issues that it raised. First, their Honours quoted Coco v The Queen (1994) 179 CLR 427 at 437 to insist that it is only clear language in the legislation itself that precludes the operation of the Principle of Legality: “the courts should not impute to the legislature an intention to interfere with fundamental rights. Such an intention must be clearly manifested by unmistakable and unambiguous language.” Further on this point, their Honours indicated that “the Principle of Legality will have little if any role to play in a context where the objects or purpose of an Act contemplate curtailment of particular rights.”

Their Honours also addressed the controversy surrounding the principle, questioning whether the “Principle of Legality is properly described as a principle at all” due to its nature and sphere of operation. Most notably, however, their Honours cautioned that the principle “must be applied with care” – it is not of “universal application and the assistance to be gained from it varies widely.”

The Principle of Legality in Context

In the next part of the judgement, their Honours gave attention to the six rights [14] on which the Henry Applicants relied for their argument:

1ai) The right to bodily integrity – at common law, the right to bodily integrity is recognised and “so much may be accepted” [95]. Despite this, the impugned orders did not mandate or compel citizens to be vaccinated and therefore the right to bodily integrity was not impaired by any of the impugned orders.

1aii) The right to earn a living or a right to work – the right to earn a living or to work is not recognised at common law in any strict sense. As such, “to the extent that people’s ability to work was directly or indirectly affected by the Impugned Orders, they were not invalid by reason of the operation of the Principle of Legality” [104].

1aiii) The right not to be discriminated against – the primary judge’s analysis at [201] “…protection from discrimination is not a right, freedom or immunity protected by the Principle of Legality” was quoted by their Honours in the appeal case.

1aiv) The right to privacy – the common law has not recognised any tort of protecting invasion of privacy, and therefore it “cannot be suggested that the asserted ‘right’ is of such a character or quality as to engage the Principle of Legality” [107].

1av) The right to silence – whilst it may be accepted to be a fundamental right which engages the Principle of Legality, “it will only be so when that ‘right’ is understood in the context in which it is most often used, namely, the right to refuse to answer questions from law enforcement officers or judicial officials” [109].

1avi) Privilege against self-incrimination – their Honours agreed with the primary judge that whilst this right engaged the Principle of Legality, it was not violated by any of the impugned orders. The impugned orders, far from the requirement to “produce evidence of identity, residence and vaccination status having a tendency to incriminate” [9], the requirement had the “opposite, exonerating effect, as production of this material would permit an authorised worker to take advantage of the carve out contained in the orders to travel outside a specific area…” [9].

Concluding, their Honours stated that none of these rights were infringed, even remotely or indirectly, by the Impugned Orders.

Analysis

The Kassam and Henry proceedings reveal how the courts might apply the Principle of Legality in the present day. The judgement of Bell P on appeal offered particular insight into how the Principle of Legality is considered by the courts:

- The principle “will have little if any role to play” [85] where the Act’s purpose contemplates rights being abrogated. The idea that the principle is not of “universal application” [84] again shows that the principle is only occasionally useful, and dependent on the context in which it is raised.

- The principle may not apply “if the interference with fundamental rights…is slight or indirect or temporary” [87]. This means that where an Act includes measures which slightly, temporarily, or indirectly affects fundamental rights, the Principle of Legality might not apply to preclude such measures.

- The strength of the principle is “correlative to and var[ies] with the strength or fundamental nature of the right(s) involved” [90]. As such, if a fundamental right is considered very important (such as the right to bodily integrity), then the Principle of Legality will too be considered important and operate to protect that right.

The above observations made by Bell P downplay the role of the Principle of Legality both generally and in the context of public health risks and his Honour’s observations echo the retreat from the Principle of Legality in the Australian judicial system in recent years. Downplaying the importance of the Principle of Legality and espousing notions such as the uncertainty of emergency situations and temporal limits on restrictions, may pose threats to our rights in the future. It is not debated that in times of emergency different measures are required compared to those needed during times of peace; however, these measures should not be at the expense of our fundamental rights, freedoms and immunities.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________