The Voice Referendum:

The Argument for Voting NO

First Nation’s Voice to Parliament

Why you should not vote YES at the Voice Referendum

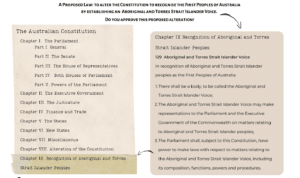

The Voice Referendum is more than recognition and inserts a new race-based Chapter into the Constitution

The real purpose of this referendum is to change our system of government by injecting a permanent element of racial privilege into the heart of the Constitution. It would give Indigenous Australians – and their descendants for all time – a second method of influencing public policy that goes beyond the benefits of representative democracy that are already enjoyed by all citizens regardless of race.

It would constitutionalise a race-based lobby group, equipped with a separate bureaucracy, that would give Indigenous citizens the ability to have an additional say on every law and administrative decision, not just those relating specifically to Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.

Although Constitutional recognition of Indigenous people is a worthwhile goal, this referendum should be rejected as it introduces a new entity within the Constitution with almost unlimited scope that threatens equality of citizenship in Australia.

Constitutional recognition of Indigenous people is desirable and can be achieved. However, this referendum on the Voice is the wrong way to achieve that goal as it creates a Constitutional entity with unlimited scope that erodes a fundamental principle of democracy, the equality of citizenship.

It is simply incorrect to equate opposition to the proposed Voice with opposition to constitutional recognition of Indigenous people. Most people of goodwill would readily accept a constitutional change that recognised Indigenous people were the first occupants of this continent.

“In Australia, there is no hierarchy of descent.. there must be no privilege of origin. The commitment is all. The commitment to Australia is the one thing needful to be a true Australian.”

– Bob Hawke, Former Prime Minister 1988

The problem with the current model for the Voice comes down to two associated issues:

- The unlimited scope of the subject matter with which the Voice can involve itself

- Equality of Citizenship where all Australians should be equal not just before the law, but before those who make the law and those who apply the law.

Chris Merritt speaking at the Rule of Law Conference.

Click here to read all of Chris’ commentary on the Voice

“Eight years ago I saw nothing wrong with requiring parliament to listen to Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders before using its power under section 51(xxvi) of the Constitution to make special laws that only affect Indigenous people. I still hold that view. This early model is what many people believe they are being asked to endorse. They are wrong.

This is not what is on offer at this referendum.”

– Chris Merritt, Vice President of the Rule of Law Education Centre and Legal Affairs Contributor to the Australian Newspaper

Unlimited Scope

a. Support for a Voice that provides advice on laws that relate only to Indigenous people

There is a legitimate argument that Indigenous people should be heard before parliament makes special laws about them under the Constitution’s race power in section 51(xxvi). In practice, that power has only been used to make laws on Indigenous affairs.

So because Indigenous people are the only Australians singled out by race for special laws, there is a logical argument for matching that power with a requirement that they should be heard before that power under section 51(xxiv) is exercised. It would therefore make sense to establish a Voice if it were limited to providing advice to parliament, not the executive, on laws enacted under section 51(xxvi). It might even be feasible to give it a flexible boundary so it could provide advice on matters that have a specific impact on Indigenous people that goes beyond the impact on the general community.

It is perfectly logical for Indigenous people to have a say before parliament makes special laws on the basis of race that affect them alone.

b. Indigenous Voice extends beyond Indigenous matters

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

-Proposed section 129(ii)

The jurisdiction of the Voice extends beyond matters that relate only to Indigenous affairs and includes any matter that relates to Indigenous peoples. The Voice is free to involve itself in any debate that affects the broader community so long as it relates to Indigenous peoples.

On January 23 Noel Pearson told Patricia Karvelas on ABC radio: “There is hardly any subject matter that Indigenous people would not be affected by and would not want to provide their advice to parliament.” Indigenous constitutional lawyer Megan Davis, who helped develop the Voice, shares this view. On December 21 last year she was asked on ABC television what issues Indigenous Australians wanted to talk about to parliament through the voice.

Davis’s answer: “At this point, virtually every issue.”

Then on July 5, Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney asserted that she “will ask the Voice to consider four main priority areas; health, education, jobs and housing.” Her statement validates these criticisms that the Voice would not be limited to areas of critical importance to Indigenous people but instead would have a remit that goes right across the Board.

If the government had wanted to focus the Voice on Indigenous affairs, or on matters that relate only to Indigenous people or even primarily to Indigenous people, it would have included such qualifications in the words that would be inserted into the Constitution.

“It is difficult to think of an issue that would be beyond the scope of the voice in its proposed form, as surely every law or policy of general application would be considered to be “matters relating to” Indigenous Australians in the same way as they are matters relating to all other Australians.”

– Lorraine Finlay, Human Rights Commissioner and former constitutional law academic

“The voice will be able to speak to all parts of the government, including the cabinet, ministers, public servants, and independent statutory offices and agencies – such as the Reserve Bank, as well as a wide array of other agencies including, to name a few, Centrelink, the Great Barrier Marine Park Authority and the Ombudsman – on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.”

– Megan Davis and Gabrielle Appleby, Voice Proponents

Equality of Citizenship

In the referendum we are being asked to constitutionalise a race-based lobby group, paid for by taxpayers, that could involve itself not just in debates on Indigenous affairs, but in debates about all matters of public policy, all proposed laws and all administrative decisions.

It will be empowered to make representations that reach into the executive branch of government, and not just the parliament.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

-Proposed section 129(ii)

That extended scope means we are being asked to constitutionalise a system of racial preference. Extending the jurisdiction of the Voice beyond Indigenous affairs, as proposed by the government, cannot be reconciled with the idea that all Australians should be equal not just before the law, but before those who make the law and those who apply the law.

It would give one group of Australians an entitlement to additional and unjustified influence over all public policy, all law making and all public administration.

“The inclusion of the proposed s129 [new Voice chapter in the Constitution] would mean that we become a nation where, whenever we or our ancestors first came to this country, we are not equal”

– the late David Jackson AM KC, pre-eminent Constitutional Barrister who had appeared in hundreds of matters in the High Court of Australia

Consider what this country would look like if this referendum succeeds. Those with the right genetic inheritance – and their descendants for all time – would gain an additional method of influencing politicians and officials that would surpass the normal rights of citizenship. The Voice would be empowered to make race-based representations about all areas of public administration and all new laws. Public servants would be in a truly dreadful position. Instead of making decisions according to law and the instructions of their superiors, they would need to consider representations from an institution of state whose only purpose would be to inject racial preference into public administration. Every federal minister and every decision maker in the federal public service could be at risk unless they inform the Voice before making decisions, provide information about matters awaiting decision, wait for a response from the Voice and generate a paper trail showing the views of the Voice have been considered. How much information will ministers and public servants be required to give the voice about decisions they propose to make? How long would ministers and public servants need to wait while the voice considers its position?

As Paul Kelly, Editor-at-Large of the Australian newspaper recently said

“The Voice contradicts the principle of equality of citizenship that enshrines and binds together our nation. The Voice is based on the principle that we have different constitutional rights depending on our ancestry. We need to think about that as a country. And think whether or not we really want that to happen. The Voice contradicts the principle of equality of citizenship that enshrines and binds together our nation…

This is a change in the Constitution that, being realistic, would be forever.

What will that mean for the unity of our country?”

Racial preference never ends well.

Equality of citizenship is fundamental to what it means to live in a democracy.

It is reinforced by the fact that the source of Australian sovereignty is the people of this nation – all of them, regardless of race or national origin, and regardless of whether they arrived yesterday or have antecedents who arrived 60,000 years ago. If you believe everyone should be equal in the eyes of the law and in the eyes of those who make and administer the law, this referendum must be rejected.

Additional Resources from the Rule of Law Education Centre about the Upcoming Referendum and the Indigenous Voice

Constitution and the Voice Referendum for Beginners

Why does it matter if the Voice is a separate chapter in the Constitution?

Come watch our video and check out the explainer which looks at what the purpose of the Constitution is, what the different chapters are and how they form the key features of government (including Separation of Powers and Division of Powers) and why a referendum is necessary to change the Constitution. Click here to learn more about the Constitution and where the referendum fits in.

Confused by the different claims on the Yes/No Official Pamphlet?

Legal Experts have also said about the Indigenous Voice

“The Indigenous Voice would have its own chapter. While distinct from Parliament, the Executive and the Courts, the Indigenous Voice would be accorded a similar constitutional status”

– Professor Aroney, Professor of Constitutional Law at The University of Queensland and Professor Gerangelos, Professor of Constitutional Law at The University of Sydney

“Given its text and place in the Constitution, one of its architects, law professor Gabrielle Appleby, says the voice will be “a foundational institution of state” and imagines the voice as a fourth arm of government. It is a significant new body that will introduce profound changes to our system of government.”

– Louise Clegg SC, Barrister

“Proponents say it will lead to unity and reconciliation. I think it is far more likely to lead to disunity, bitterness and a sense that some groups in Australian life get special treatment soley based on birth”

– Professor James Allan, Garrick Proffessor of Law, The University of Queensland

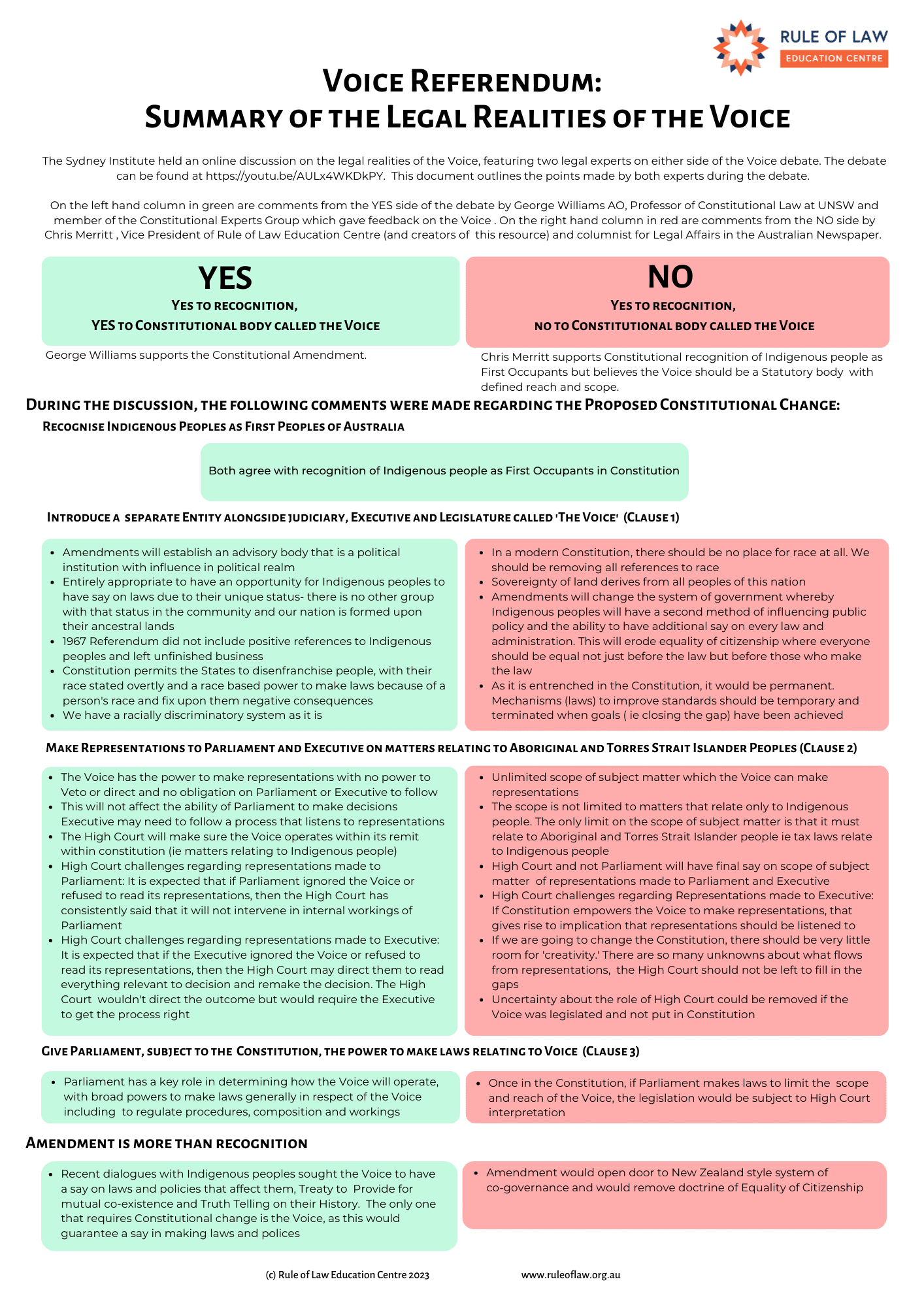

Legal Arguments for and against the Voice

On the left hand column in green are comments from the YES side of the debate by George Williams AO, Professor of Constitutional Law at UNSW and member of the Constitutional Experts Group supporting the Constitutional Amendment. On the right hand column in red are comments from the NO side by Chris Merritt , Vice President of Rule of Law Education Centre and columnist for Legal Affairs in the Australian Newspaper. Chris Merritt supports Constitutional recognition of Indigenous People as First Occupants but believes the referendum should be rejected. Click here to read more.

Paul Kelly, Editor-at-Large, The Australian

Speaking at the Robin Speed Memorial Lecture: Rule of Law Series

Equality before the Law and the Magna Carta: A right worth defending

The Voice Referendum: What the wording should include to justify a YES Vote

In the Media: Articles and Appearances regarding the Voice

The VOICE:

The detailed argument to Vote NO

Chris Merritt, 3 February 2023

Introduction

The real issue at this year’s indigenous voice referendum is a question of principle: Will we abandon the egalitarian nature of Australian democracy?

Will we, in other words, join the crackpots of history by introducing into our Constitution the concept of racial preference that lies at the core of this referendum? Or will we defend the ideals of liberal democracy that emerged in revolutionary America and France?

We are being asked to give one racial group – and their descendants for all time – constitutionally guaranteed additional influence over all areas of public policy. If you tick the right race box you would gain political influence exceeding that enjoyed by every other Australian.

The proponents of the yes case see things differently.

Some have argued that the voice would be merely symbolic; a benign way of showing solidarity with indigenous people by giving them a say on matters that affect them. Others have described it as a path to empowerment.

But that’s not the real story. This referendum is not about reconciliation. Nor is it about symbolism and being nice. It is about establishing a new institution of state that would permanently change our system of government.

It would require us to abandon equality of citizenship by giving constitutional standing to a race-based entity that could go beyond indigenous affairs and involve itself in all public policy debates.

The proponents of the voice say it is the solution to years of policy failures on indigenous affairs. They say it is justified because parliament can already make special laws on indigenous matters and this will merely allow indigenous people to have a say on those laws.

But if closing the gap on disadvantage and making better laws on indigenous affairs were the true goal, why has the constitutional provision been drafted in a way that would permit this entity to dissipate its efforts across the entire range of federal public policy?

Why did the proponents of this change decline to confine the voice to matters that only affect indigenous people, or even primarily affect indigenous people?

Without such limits, this looks like an attempt to establish a shadow government that would be free to develop policies on everything. Those policies would be formally framed as advice but, according to prime minister Anthony Albanese, it would be a brave government that ignored its advice.

If the prime minister’s assessment is correct, it would mean the voice would sit uneasily alongside the doctrine of responsible government in which governments are held accountable for their actions first to parliament and then to the people.

In the new world of the voice, the business of government would never be the same.

Governments would inevitably find themselves making trade-offs not just with the opposition and various groupings in the senate, but with members of the national voice and their masters at the regional and local voices that are yet to be established. These local and regional groups would control appointments to the national body and would be the new powerbrokers.

Exactly how voice members will be appointed is just one of the details that has not been resolved. But those who have worked on this proposal have designed an institution that would suffer from a democratic deficit.

And because the voice would be at the heart of our system of government, that malaise would weaken Australian democracy.

The final report of the Indigenous Voice Co-Design Process raises the prospect that some members of the voice may simply be nominated by the local and regional voices while others might be elected. That erosion of democratic principle weakens the case for incorporating such an entity in the Constitution.

But that is not the only departure from democratic principle. One of the most startling proposals in that report is that the distribution of members of the voice between the states should be done in a manner that can only be described as a gerrymander.

According to figures published in September last year by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, NSW has 339,546 Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders which gives that state 34.5 per cent of the nation’s indigenous population of 984,002 – the highest proportion of any state.

Yet the report of the Indigenous Voice Co-Design Process would give NSW a total of just three representatives on the proposed 24-member voice. So the state with 34.5 per cent of the nation’s indigenous people would receive 12.5 per cent of the seats on the voice.

Other states with three seats on the voice would be South Australia which has just 52,083 indigenous people, the Northern Territory (76,736 indigenous people) and Western Australia (120,037). Together, those three states would have nine seats on the voice – or three times the representation of NSW – yet their combined indigenous population is 248,856 which is 90,690 fewer than the indigenous population of NSW.

That report, co-chaired by Tom Calma and Marcia Langton, would amount to a raw deal for indigenous people in NSW and an extremely favourable deal for those in Queensland. It treats the Torres Strait Islands, which are part of Queensland, as a separate jurisdiction and would give them two seats on the voice plus an additional seat for those islanders who reside on the mainland.

When those three seats are included in Queensland’s tally, the sunshine state would have six of the 24 seats on the voice – twice as many as NSW. Yet the ABS population estimates show that Queensland has just 273,224 Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, which is 66,322 fewer than in NSW.

These departures from democratic principle would not be tolerated in any other representative body, state or federal, that is part of this country’s system of governance. Yet this plan for the voice would deprive the nation’s largest cohort of indigenous citizens – those in NSW – of fair treatment.

These shortcomings were not mentioned by the prime minister when he rose in the House of Representatives on November 30 last year holding a copy of the Calma-Langton report, and said: “There are 280 pages of detail about how the voice will operate.”

The proponents of the yes case need to explain why the interests of indigenous people in NSW are considered less important than those of indigenous people in Queensland and other states.

If they have other ideas for the voice, now is the time to disavow Calma-Langton and make the next plan public.

The real issue for the broader community concerns the adverse impact of the voice on day-to-day policy-making. Because the voice would have an unlimited jurisdiction and a narrow race-based constituency, it is entirely foreseeable that government policy on key issues could be skewed away from the broader national interest in order to appease the voice or gain its support.

Constitutionally, governments would still need to maintain the confidence of parliament. But if Albanese is right, political reality would give all governments a strong inventive to placate the voice.

Formally, the voice would merely be providing advice. But in practical terms, it would have real influence over the development of public policy affecting the broader community while remaining accountable only to its race-based constituency.

All groups in society, including indigenous communities, have interests that need to be balanced. Giving constitutional standing and public funding to any single community group would rig the process of balancing conflicting interests and allocating resources, which is the core business of government.

Rejecting such a distortion of the democratic process does not mean closing our minds to the views of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous people – like everyone else – already have a voice on all matters of public policy through their rights of citizens.

Most people may not be aware of how far the back-room conversation has moved on from symbolic recognition of indigenous Australians. At some point the objective became “substantial” recognition. And the design of the voice went beyond the creation of an advisory group on indigenous affairs to something much more ambitious.

On the table today is a proposal to create a permanent institution of state that would be entitled to develop and prosecute its own policies independently of parliament and the government of the day. It would have everything it needed to establish itself as a shadow administration that, unlike parliament, would not be required to serve the broader national interest, but would instead give priority to its own relatively narrow sectional interests.

The referendum raises a number of questions in relation to:

1) Equality between all Australians.

2) The scope and power of the voice.

This conversation has become complex and confused, mainly because of the lack of community-wide consultation to date. The blame rests entirely with the government which chose to break with tradition by failing to present official arguments for and against the proposed change, as well as detailed and independent legal analysis.

In past referenda, federal governments fostered debate by providing a pamphlet containing 2000 -word essays giving the official cases for and against the proposed changes. But this time that will not happen and the government even tried to stifle debate by implying that those with concerns are racists.

On November 25 last year, just before the abandonment of the traditional information pamphlet became official, Pat Dodson, the government’s special envoy on reconciliation, told a panel discussion on the voice in Melbourne: “The government is not interested in supporting any racist campaigns, which will have an impact on the question of the pamphlet.”

1. EQUALITY

Do we want to establish a Race-Based Institution of Inherited Privilege?

To gain an insight into the importance of equal treatment, consider this: Last year marked the sixtieth anniversary of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1962 that granted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders the option of voting at federal elections. Mandatory voting at those elections, which followed in 1983, put indigenous people on exactly the same footing as all other Australians.

This took far too long, as did the abolition of the last remnants of the white Australia policy which only took place between 1966 and 1973. Yet those changes show what can be achieved when nations are guided by the doctrine of equal treatment regardless of race.

Equal treatment is fundamental to what it means to be Australian.

It helps explain why, in 1902, the newly established federal government was among the world’s first to enfranchise women voters. South Australia was even earlier, giving women the vote in 1894.

These great reforms all gave effect to the principle of equality. It would be tragic to discard a principle that has served us so well, particularly if this were done as part of some misguided attempt to make amends for the racial intolerance of the past. The damage inflicted by racist policies cannot be denied. But the very source of that damage was the absence of equal treatment. We cannot repeat that mistake.

The referendum that now confronts the nation invites us, once more, to exclude indigenous people from the great principle of equality that was forcefully expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence and which is present in true democracies. Our own history shows that the denial of this principle, regardless of the motivation, leads to catastrophic outcomes.

If this referendum succeeds it would not make up for past injustice. It would do the reverse. It would entrench racial preference, placing this country in the same category as Malaysia, where ethnic Malays enjoy legally sanctioned racial preferences over citizens of Indian and Chinese ethnicity. It would show that we have learned nothing from the racism of the past.

This is the antithesis of the principle espoused by American revolutionaries Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin who considered it self-evident that we are all created equal. Revolutionary France, under Jefferson’s influence, embraced this idea in its Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. It is also present in the first sentence of the first article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was drawn up by the United Nations in 1948 and Australia was one of the original signatories. Article one says: “All human beings are free and equal in dignity and rights . . . “. Article two says: “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this declaration without distinction of any kind, such as race . . . “.

There is another problem. On January 28, Janet Albrechtsen wrote in The Australian that if the referendum succeeds, it may well amount to a serious breach of Australia’s obligations under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. If legal advice had been obtained from the Solicitor-General she wrote that it might have found that permanently entrenching racial preferences will make this nation a genuine international pariah.

If the referendum succeeds, everyone would still have the same right to vote and to seek to influence public policy. But those represented by the voice would have something extra.

They would be represented not only by their members of parliament but by a separate lobby group with constitutional standing, public funding and its own bureaucracy.

Those who quibble about whether this would create an extra right for indigenous people have missed the point. The reality, regardless of how it is termed, will be that Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, through their representatives on the voice, would have greater constitutional standing than people of other races.

This would put an end to the idea that all Australians are entitled to an equal say on how this nation is governed. It would entrench racial division and kill reconciliation by fostering resentment against the beneficiaries of such an obviously unfair and unprincipled system.

Australian democracy might not be perfect. But it is the result of a great multicultural project, drawing on the doctrine of equal treatment and the experience of all peoples represented by our federal and state parliaments.

It involves weighing up the needs of all groups taken together and deciding policy that works in the national interest of the whole community.

Putting that collective project first does not make the “no” case racist, or against reconciliation. Every day the peoples of this nation acknowledge Aboriginal presence like never before and celebrate its culture and contributions.

Embracing the voice would mean embracing a system of inherited privilege which has no place in modern democracies.

2. SCOPE

Do we want a Race-Based Institution to propose its own policies affecting the whole community?

One of the main flaws in the referendum proposal is that it would give the new institution unlimited jurisdiction. This was made clear on January 23 by Noel Pearson, one of the key proponents of the voice. He told Patricia Karvelas on ABC radio: “There is hardly any subject matter that indigenous people would not be affected by and would not want to provide their advice to parliament.”

Indigenous constitutional lawyer Megan Davis, who helped develop the voice proposal, shares this view. On December 21 last year she was asked on ABC television what issues indigenous Australians wanted to talk about to parliament through the voice.

Davis’s answer: “At this point, virtually every issue.”

“The Commonwealth – and cascading through the federation to the states and territories – will be compelled to listen. That’s the key thing,” Davis said.

The preliminary wording of the proposed constitutional provision shows that the scope of the voice would not be limited to indigenous affairs such as land rights.

It would be free to involve itself in any debate that affects the broader community so long as it also relates to Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.

It is simply incorrect to assert that if this referendum succeeds, parliament could fill in the details later and confine the reach of the voice to matters that relate only to Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.

Such a restriction would risk being struck down as inconsistent with the words of the constitutional provision which contain no such restrictions.

The prime minister unveiled the preliminary wording of this provision in July, 2022, at the Garma cultural festival in Arnhem Land. The second sentence of that three-sentence provision says:

“The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice may make representations to Parliament and the executive government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.”

So what would this include? Native title to land clearly relates to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – but so does taxation and economic policy. Indigenous people pay taxes and are affected by economic policy.

The involvement of the voice would be triggered by the existence of a matter that relates to indigenous people. The fact that such a matter might primarily relate to the broader community would be irrelevant. If it relates to indigenous people as well, the voice could have a role.

This was clearly intentional.

If those responsible for this provision had wanted to confine the voice to indigenous affairs, or to matters that relate only to indigenous people or even primarily to indigenous people, they would have included such qualifications in the provision unveiled in July. That was not done and it would be too late to revisit this issue if the referendum succeeds.

Conclusion

There is one inescapable fact about modern Australia that explains why indigenous people do not need a separate institution in order to make their views clear to parliament: The proportion of seats in federal parliament held by indigenous Australians is already greater than their proportion of the nation’s population.

Figures compiled by the Parliamentary Library in August, 2022, show Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders make up 4.8 per cent of the members of federal parliament, and just 3.2 per cent of the total population.

Their voices led the debate over the breakdown of law and order in Alice Springs.

This referendum should be rejected – not just because it is wrong in principle but because the proponents of this change have declined to provide the community with enough information to make a fully informed decision.

The government bears the onus of explaining the requirements, implications and restrictions that would arise from the proposed constitutional provision. That requires the publication of independent legal advice on the proposed provision – preferably from Solicitor-General Stephen Donaghue rather than those associated with the “yes” case.

That has not happened.

This is quite apart from the failure to provide an outline of the statute that would create the new entity if the referendum succeeds. Requiring such information is not unreasonable, nor is it racist.

These failures are a departure from normal practice and should not be rewarded. They show insufficient respect for the fact that the Constitution draws its legitimacy not from politicians and insiders but from the entire community.

We are being asked to abandon equality of citizenship – one of our most important values – in order to insert a divisive institution into our system of governance while having only a limited idea about its structure and powers, how it would change the business of government and the implications that could be read into the new provision by the High Court.

This referendum should be rejected – primarily because it is wrong in principle but also because the proponents of this change have failed to provide the community with enough information to make a fully informed decision.

They have forgotten that the Constitution draws its legitimacy from the entire community – not from politicians and insiders.