Case Note: Kathleen Folbigg

Introduction

Once labelled Australia’s “most hated woman” and “worst female serial killer”, Kathleen Folbigg (‘Folbigg’) was unconditionally pardoned by Governor Margaret Beazely and released from prison on June 5,2023, following 20 years in jail. She was exonerated and her convictions quashed by the Criminal Court of Appeal on December 14, 2023.

In 2003, Folbigg was found guilty of killing her 4 young children – Caleb, Patrick, Sarah, and Laura – over a period of 10 years. This case note will analyse elements of the investigation, coronial inquests and murder trial, including the successive appeals and judicial inquiries into her conviction. It is recommended that this resource is read alongside the timeline and the document containing a comprehensive procedural history and analysis of some of the evidence presented.

Case Summary

In 2003, Kathleen Folbigg was convicted of the manslaughter of her first child, the intentional infliction of grievous bodily harm upon her second child, and the murders of her second, third, and fourth children. Several failed appeals subsequently followed, as did a judicial inquiry initiated in October 2018 and heard in March 2019, with a finding of no reasonable doubt as to her convictions being returned in July 2019.

On March 2, 2021, a petition to pardon Kathleen, endorsed by world-renowned scientists and medical practitioners, was delivered to the Governor of NSW. As a result, another inquiry was launched, finding that Folbigg’s children had died of a rare genetic disease that was not identifiable at the time of her initial trial. In 2023, 20 years after her imprisonment, Folbigg was unconditionally pardoned and released from prison.

Case Overview

Folbigg and her husband Craig had their first child, Caleb, on 1 February 1989. Caleb had a tendency to stop breathing while feeding, and he was subsequently diagnosed with a “floppy larynx”. It was believed to be a mild illness that he would grow out of. On 20 February 1989, Caleb died. His death was deemed to be natural, and a diagnosis of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (‘SIDS’) was made by autopsy.

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (‘SIDS’)

A diagnosis of SIDS is usually made when a child aged between two and six months, dies suddenly and unexpectedly, and there is no reason to suspect an unnatural cause of death.

On 3 June 1990, the couple’s second child, Patrick, was born. During mid-October, Patrick lost consciousness and was taken to the hospital with respiratory distress. He later regained consciousness, but he was diagnosed with epilepsy and cortical blindness. On 13 February 1991, Patrick died. It was deemed by autopsy that Patrick’s airways had been obstructed during an epileptic seizure.

On 14 October 1992, their third child, Sarah, was born. She was a happy and healthy baby, however, on 30 August 1993, Sarah died. The autopsy attributed her death to SIDS.

On 7 August 1997, the Folbigg’s had their fourth child, Laura. Like Sarah, she was a healthy baby., On 1 March, 1999, at almost 19 months old, Laura died. Her death was initially determined to be a viral infection which had inflamed the heart muscle. However, the subsequent autopsy found her death to be ‘undetermined’. This finding was made when the autopsy doctor learned about the deaths of Laura’s siblings. He notified the police, believing that smothering could not be ruled out as a cause of death.

On the day of Laura’s death, the NSW police began a murder investigation into the deaths of all four children, believing that Folbigg might have been responsible for them. They believed this because she had been the only one in their presence when each died or had been the one to find the children deceased. In each instance, her husband was either at work or asleep.

During the investigation, journals and diaries were taken by police, of which entries were later used as evidence to admissions of guilt in court.

On 19 April 2001, Folbigg was arrested and charged with the murders of her four children.

Analysis

How Did the Law Reflect Moral and Ethical Standards?

Moral and ethical standards within most societies condemn murder to the highest degree, and the murder of infants (infanticide, punishable under s 22A of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW)) is deemed to be an even more serious crime. This moral standard is supported by Article 19 of the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child, which aims to protect children ‘from all forms of physical or mental violence.’

This consideration is largely due to the shared sentiment that infants are not yet capable of any intentional wrongdoing and thus, are the least deserving of harm. They are also among the most vulnerable class of victims and are completely incapable of self-preservation or defence. These values contributed to Kathleen’s harsh treatment under the law and the public media controversy surrounding her case.

Society’s moral and ethical standards were reflected clearly in Folbigg’s initial sentence, particularly her non-parole period of 30 years. In His Honour’s sentencing remarks, Justice Graham Barr stated that “The need for the sentences to reflect the outrage of the community calls for the imposition of an effective sentence which incorporates an unusually long non-parole period.” [100]

Conversely, the petitions calling for Folbigg’s release in 2015 and 2021 voiced the moral and ethical standards of those within the community who believed in Folbigg’s innocence given the emergence of new evidence.

Section 77 of the Crimes (Appeal and Review) Act 2001 (NSW) sets out the various outcomes that petitions are capable of achieving, such as granting additional avenues of appeal or in Folbigg’s case, initiating a judicial inquiry. Petitions are a way of ensuring that the moral and ethical standards of the community are included in the outcome of a trial, especially in high-profile cases.

What was the role of discretion?

Discretion is defined as the act of making a decision. This can be a particularly complicated process in the criminal justice system, where the interests of all parties, the moral and ethical standards of the community, and the decision-maker’s own legal or moral obligations and standards must all be weighed up.

The main examples of discretion in the Folbigg case occur when:

- The pathologist examining the circumstances of Laura Folbigg’s death referred the matter to the police.

- The police investigation regarding what type of evidence to gather, charging Folbigg with murder, and granting her bail in 1999.

- Folbigg’s (then) husband, Craig, submitted Folbigg’s diary entries to the police to be used against her as evidence in court.

- In Folbigg’s trial before the Supreme Court (2003), Justice Barr used his discretion, in combination with sentencing considerations, to sentence Folbigg to forty years imprisonment with a non-parole period of thirty years.

- In Folbigg’s appeal before the NSWCCA (2005), the Justices of Appeal decided to reduce her sentence to 30 years imprisonment with a non-parole period of 25 years.

- The many appeals that were dismissed.

- The Governor of NSW used her discretion to initiate a judicial inquiry.

- Following the 2022 Judicial Enquiry, Bathurst KC used his discretion, and held there was reasonable doubt concerning Folbigg’s guilt, leading to her being pardoned.

Do you think it is fair that, depending on the judge’s discretion, Folbigg’s sentence could vary by as much as 10 years? How does the legal system justify providing judges with such enormous discretionary power?

Our legal system deems that judicial discretion is entirely necessary to weigh up all factors in determining a sentence. Although this may lead to inconsistent outcomes as it did for Folbigg, mandatory sentencing considerations and guidelines are established in our legal system to limit the arbitrary use of discretion and prevent unfair sentences.

Furthermore, if an unfair sentence does occur despite these measures, the right to appeal allows people to seek a re-evaluation of the decision through legal process. This appeal system also serves a check on judicial power, as does judges needing to give detailed reasons for their decisions.

How Did the Law Balance the Rights of Victims, Offenders and Society?

The rights of victims

In a murder case, the rights of victims may be hard to grasp as they cannot be given compensation in any form. Despite this, the legal system strives to uphold the victims’ right to be provided justice by uncovering the truth and bringing punishment upon those responsible. This includes all victims, whether they are young children, every day people or serious criminal offenders.

The rights of society

In any criminal case, balancing the rights to privacy of the accused are in conflict with providing justice to vulnerable victims through open justice processes. The publicity that the case received over the course of its time impeded on Folbigg’s right to privacy, particularly with regard to her journal entries and own traumatic family history. These factors may also have impacted on her presumption of innocence. However, there is a need for transparency in investigation and trial processes in order to uphold the rights of society and ensure that offenders are dealt with in a way that reflects the needs of the community.

However, contrasting this, the public also had a role in Folbigg’s eventual release through the two petitions signed by experts and members of the public, supporting the recognition of new scientific analysis that was believed to create doubt as to the validity of her role in the deaths of her children. This indicated that an inquiry into her conviction was in the interests of society. The Governor responded to the public’s request and the inquiry was launched.

The rights of the accused/offender

Because of the significant media publicity concerning the case, and the extreme tragedy and unusual occurrence of the deaths of 4 children from one family, the court faced challenges in upholding Folbigg’s right to a fair and prompt trial, as well as her presumption of innocence. Orders were made for her protection against extrajudicial punishment in the media and in prison, particularly with regards to the fact that her father had murdered her mother when she was 18 months old as this could serve as influential factor regarding her innocence.

Blackstone’s Law states that ‘It is better than ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer’. This is a widely accepted principle in the Australian criminal legal system. To this end, the Folbigg case has been dubbed as “one of the gravest miscarriages of justice in Australia’s history” (The Guardian, 2023), demonstrating that false punishment is one of the worst outcomes that a justice system could come to.

Moreover, the degree to which Folbigg was wrongly punished was grave. She spent twenty years in prison before her pardon was granted, and it is likely that without the non-legal measures that would eventually lead to her release, she might have served her full sentence.

Sentencing and Punishment

Initial Sentence

In the initial sentence imposed upon Folbigg following her trial in 2003, a total of 40 years imprisonment with a 30-year non-parole period, Justice Barr stated the purposes of sentencing that were most relevant to the case included:

- “Because of the intractability of her condition, the offender’s prospects of rehabilitation are negligible.” [98]

- “The need for the sentences to reflect the outrage of the community calls for … an unusually long non-parole period.” [100]

- “So does the need generally to deter persons from committing crimes like these, which are so difficult to detect.” [100]

From these statements, it is clear that denunciation, general deterrence, and the protection of the community were the major purposes of sentencing. Justice Barr also explained that rehabilitation would not likely be successful and thus, was not a relevant purpose in Folbigg’s sentence.

Do you agree with these purposes of sentencing? Can you think of any more that would be relevant?

Justice Barr also stated the following in regard to sentencing guidelines:

- “Her offences fell into the worst category of cases, calling for the imposition of the maximum penalty.” [93]

- “The offender’s dysfunctional childhood provides … significant mitigation of her criminality.” [93]

- “She was throughout these events depressed and suffering from a severe personality disorder”. [94]

- “Gaol … will be particularly dangerous for the offender … she will serve her sentences the harder and is entitled to consideration.” [99]

To sentence someone to the maximum penalty of the offence they were charged with, the judge must be satisfied that the particular offence fell within the worst category of cases. For example, if a defendant had murdered someone whom they believed was threatening or provoking them, the presiding judge may not sentence them to life imprisonment. In Folbigg’s case, the murder of four infants was held to be of the ‘worst category of cases’ and thus warranted the maximum sentence. His Honour had used this basis as a ‘starting point,’ and applied further considerations to account for mitigating factors.

Justice Barr stated that Folbigg’s depression and severe personality disorder were factors that mitigated the severity of her sentence, resulting in the 40 years imprisonment sentence that she was ultimately handed.

If you, like Justice Barr, were obliged to follow the jury’s verdict of guilty, what sentence would you believe was appropriate? Do you agree with Justice Barr’s reasoning?

What are some post-sentencing considerations that should have been implemented to better achieve fair and humane methods of punishment, treatment, and support?

Sentence on Appeal

On Folbigg’s appeal in 2005, Justice Sully gave the following reasons for reducing Folbigg’s sentence from 40 years (with a 30-year non-parole period) to 30 years (with a 25-year non-parole period):

- The original sentence was “so crushingly discouraging as to put at risk any incentive that she might have to apply herself to her rehabilitation. That seems to me to indicate… error.” [186]

- The original sentence was “a life sentence by a different name… is in my respectful opinion such as to warrant [intervention] of this court.” [189-190]

In Justice Sully’s appealed sentence, more consideration was given to rehabilitation as a purpose of sentencing, whereas in the initial sentence, Justice Barr believed that rehabilitation had low prospects of succeeding and thus, was not a priority.

Do you believe all individuals should be given a sentence that strives for rehabilitation? Do the benefits outweigh the practical costs of long-term rehabilitation projects?

Legal and Non-legal measures

Legal Measures

The legal measures which were relevant in the protection of Folbigg’s rights included her right to appeal and the process of judicial inquiry.

Folbigg made three appeals in her procedural history – one against the decision to have her four charges be heard in one trial and two against the Supreme Court’s decision in 2003.

The appeal system in Australia is designed so that errors in legal interpretation, procedure, or factual findings can be identified and corrected. The right to appeal is a powerful form of judicial accountability that often works to secure justice when one is wrongly sentenced. So why didn’t they achieve justice for Folbigg?

The primary reason why these appeals did not overturn the initial proceeding’s finding of guilt was because they all operated off the same error of fact – that there was no genetic cause for her children’s deaths. As we now know, it is possible that the cause was in fact genetic, but the level of scientific understanding in this specific area was not yet advanced enough to confirm it. This means that what is often most celebrated about the justice system – that a case is weighed only on the evidence available before the court at the time – can also be a potential limitation.

In cases where the presentation or interpretation of some evidence is reliant on the technology available at the time, that evidence’s usefulness in determining the truth is bound by the ability of the technology available to show its true meaning or role in a case. This may potentially render the courts unable to arrive at the full truth.

The legal measure of judicial inquiry was a more effective measure in securing justice, particularly the second inquiry initiated in 2021. A judicial inquiry is conducted by a judicial officer (for example, someone who has been appointed a judge by the Governor), who investigates the validity of a previous finding for any errors of fact or errors of law. They are different from an appeal as an inquiry requires either a petition to be made to the Governor of the State, or an application to be made to the Supreme Court.

Although the 2021 judicial inquiry was effective in restoring Folbigg’s freedom, it was a long and frequently delayed process that took years to achieve justice. In this case, one might argue that justice delayed is justice denied, and consider the lapse in time to diminish its effectiveness as a legal measure. Additionally, it would not have been possible without the involvement of non-legal measures in Folbigg’s story.

Non-legal Measures

Non-legal measures such as media coverage, documentaries, and public discussions shed light on the complexities of the case and the potential implications for justice.

Throughout the entire case, from its beginning in the early 2000s until Folbigg’s release in 2023, the media has played a huge role in the administration of justice, resulting in both positive and negative outcomes.

On the positive side, the public’s voice was instrumental in Folbigg’s pardon in 2023. The 2021 judicial inquiry was a result of social campaigns, petitions and protests organised by Australians who believed in her cause and saw her incarceration as a miscarriage of justice.

In particular, Folbigg’s supporters within the scientific community had undertaken significant research on SIDS-related heart defects. In an episode of 60 Minutes in 2021, some of the country’s most prestigious scientific minds shed light upon the recent breakthroughs that they were confident would explain the deaths of the Folbigg children and discharge Folbigg of their murders. In this sense, the positive outcomes of media engagement toward the Folbigg case highlight one of the primary roles of the media in the Australian legal system; to hold systems to account for the decisions made.

The actions taken by Folbigg’s supporters to spread awareness of her incarceration and to bring relevant scientific breakthroughs to the forefront of public discussion contributed greatly as non-legal measures to achieving justice.

On the other hand, the significant prejudice that Folbigg initially faced damaged her right to be treated fairly under the rule of law. These issues will be covered in the section Application of Rule of Law Principles.

The positives and negatives that had risen from public discussion demonstrated that media engagement surrounding an ongoing trial can often be a double-edged sword, and that citizens who do take part in it should be mindful of how to balance their right of free speech with the fairness of the accused’s trial. This is particularly true for high-profile cases such as Folbigg’s, in which the allegations are so alarming or emotive that ‘mob mentalities’ can often be formed within the community based on limited information and facts delivered through the media.

This is a key reason that the presumption of innocence is such an important aspect of the justice system in Australia and is so fiercely protected by court protocols and procedures, and also judicial officers, during the course of the criminal trial process.

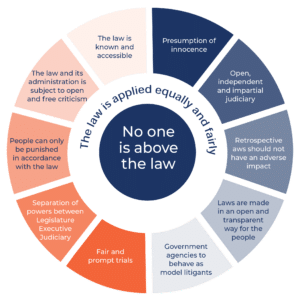

Application of Rule of Law Principles

Fair and Prompt Trials

In Australia, all citizens are considered equal before the law; therefore, all people have the right to fair and prompt trial.

Often when we consider equality before the law, we are examining the operation the justice system through the lens of offenders and ensuring that all offenders are treated equally. However, it is important to remember that equality considerations are relevant to both sides of a case – defendants and complainants. Even though the deceased in this case were young children, their right to life was seen as being just as important to others and they were afforded the same justice processes.

When decisions by a Court are made fairly, it gives legitimacy to the judicial process and instils public confidence in the Court’s determinations. Where trials are not fair, the reverse occurs: the public has little trust or respect for judicial processes or outcomes.

Prompt trials are an important principle as well. Prompt court processes ensure that innocent people falsely convicted of a crime do not suffer undue reputational damage or lose their liberty and freedom.

The Folbigg story provides an important lesson in the importance of fair and prompt trials. A period of 3 years lapsed between sending the 2015 Petition to the Governor of NSW before a decision was finally made in 2018 to hold an inquiry. It took another few months for the inquiry to commence in early 2019.

Similarly, a period of 1 year lapsed between when the 2021 Petition for another inquiry was sent to the Governor of NSW before a second inquiry was announced to take place. This inquiry finished in early-mid 2023.

During this time, Folbigg’s freedom was taken away for a significant period, when she might have been released upon a positive inquiry determination. Folbigg’s release might have happened 1-2 years earlier had the Petition been responded to promptly.

Presumption of Innocence

The presumption of innocence is often called the ‘golden thread’ running through the criminal law system. The principle ensures that all individuals are considered innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. Supporting this principle, the onus of proof is on the prosecution in a criminal trial; meaning that, the prosecution must prove each element of the offence and prove, beyond reasonable doubt, that the accused committed the offence.

Several factors can compromise the presumption of innocence that an accused must bear. Factors like reversing the onus of proof or public references to the accused’s guilt before a trial can potentially impact the presumption of innocence in practice, particularly where a jury is involved.

Folbigg’s story is a lesson in protecting an accused’s presumption of innocence. There are two ways in which this is particularly seen:

- The circulation of information by media in a way that strongly suggests the guilt of an accused before the completion of a trial; and

- In cases of extraordinary circumstances, such as the deaths of 4 children from the one set of parents in this case, the difficulty in reconciling the events can often lead people to assume that the only possible way it could have happened was at the hand of the accused, effectively reversing the burden of proof.

What were the elements of the offence that needed to be proven by the Prosecution to establish Folbigg’s guilt?

Media Coverage

After Folbigg’s arrest in 2001 and before her murder trial in 2003, she was labelled in the media as a ‘baby killer’, ‘Australia’s worst serial killer’ and ‘Australia’s most hated woman’. Despite maintaining her innocence, the media published many stories which fed into the public’s sentiment of Folbigg’s guilt.

In addition, the media released information that Folbigg’s father had murdered her mother by stabbing her 24 times when Folbigg was 18 months old. This new information impacted the tenor of media reports and community belief – adages of ‘like father like daughter’ began to circulate.

This information was inadmissible at Folbigg’s 2003 murder trial since it was significantly prejudicial to Folbigg. As such, the information was purposely kept from the jury as per the rules of evidence. However, it was later discovered that some jury members had accessed this information during the trial due to its wide circulation on the internet by media outlets. This is a significant problem since the jury must make a determination on the evidence presented at trial only and cannot conduct their own experiments or investigations into the alleged offence or offender.

This jury misconduct was later the subject of an appeal in 2007 by Folbigg, but the NSWCCA ultimately dismissed it.

An extraordinary case

Folbigg’s case was one of exceptional circumstances – the death of 4 children from the one couple, each before the age of 2.

Her conviction was based on the absence of scientific evidence supporting a genetic cause of this magnitude. During her 2003 trial, the prosecution relied on ‘Meadow’s Law’, which suggested that one sudden infant death is a tragedy, two is suspicious, and three is murder until proven otherwise. This presumption of guilt was due to the lack of a known genetic basis for SIDS at the time, and relied on the false assumption that such a basis could not exist.

This also had the unfortunate effect of having the burden of proof reversed to some degree and forcing Folbigg’s defence team to try to prove that she had not murdered her children.

When dealing with murky areas of fact, should the court not err on the side of innocence? What factors contributed to the court’s decision to err on the side of guilt?

People Can Only be Punished in Accordance with the Law

This principle is often considered a safeguard against arbitrary government discretion, ensuring that the law is well-defined, and the public can only be punished for breach of the law. But there is another important aspect to this principle: the law prescribes well-defined rules that all court processes and trials must abide by, and people can only be punished according to these rules.

An important aspect of this are the rules of evidence. The Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) strictly governs evidence that may be admitted at trial. This includes what evidence can be heard by the jury and what evidence must be left out (inadmissible evidence). This important safeguard is designed to ensure that every accused who comes before the Court receives a trial based on the same rules of evidence. It is important to note that the rules of evidence only apply to cases before the Court and do not bind an inquiry.

The rules of evidence govern the admissibility of evidence that experts may give (‘Expert opinion evidence’).

In the 2003 murder trial, several experts, including forensic pathologists and psychologists, gave evidence for both Crown and defence. Each expert who gave evidence had specialised knowledge based on training, study or experience, and their opinion was based on their particular area of expertise. As such, the rules for expert opinion evidence as prescribed by the Evidence Act were followed at trial. This meant that Folbigg would be able to be punished in a manner that was in accordance with the law and based on the the evidence.

As previously mentioned, if at Folbigg’s murder trial the Crown presented evidence to the jury relating to the fact that her father had murdered her mother, the jury would likely be dismissed, and a new trial ordered. This is because this type of evidence is inadmissible and does not follow the rules of evidence, considering it is highly prejudicial to the accused. This, and the fact that this particular piece of evidence was ruled inadmissible at trial, shows the significance the Court places on following the rules of evidence to ensure a fair trial and an accused is only punished per the stated law.

However, expert opinion evidence can also be divided depending on the perspective of the expert before the court and the prevalent and known methodologies applied at the time. This can be particularly true with evidence that relates to the interpretation of psychological state of an accused.

Despite the expert nature of evidence given at this trial, the validity of the diary entries as admissions of guilt during the 2003 trial was controversial, given the therapeutic nature that journals can have for victims of trauma. This means that the entries Folbigg made to her diaries could have been emotional responses to the deaths of her children, particularly given the lens of her childhood, rather than factual accounts, as they were treated in the murder trial and subsequent appeals. In addition, Folbigg maintained throughout all stages of investigation, trial, appeal and inquiry, that her diaries were ‘emotional dumps’ and reflections of her thoughts and doubts.

This perspective was supported by several experts at both the 2019 and 2023 inquires, and by The Honorable T Bathurst in his Memorandum to the NSW Attorney General dated June 1 2023 stating:

“The evidence given by Ms Folbigg as the circumstances of and motivation for writing the diaries was supported by the psychological and psychiatric evidence adduced at the Inquiry, none of which was substantially challenged and which I accept. The evidence that was that rather than being admissions of murder, the entries were explicable as the words of a grieving, depressed and traumatised mother, feeling guilt at the unexplained deaths of her four children, and were typically cognitions of parents of children who have died from SIDS or other unexplained or accidental causes.”

Checks and Balances

Checks and Balances operate as a safeguard to abuses of power and ensure those in power are subject to the law. To ensure the judiciary does not exceed it powers and that it’s decisions are in accordance with the moral and ethical values of society, there is a process of appeal to higher courts where decisions are reviewed.

However, in Folbigg’s case, given the lack of scientific evidence to support the genetic cause of her children’s deaths, and the reliance on her diary entries as evidence of her state of mind and actions, the appeal process did not identify the reasonable chance that the deaths were not caused by Folbigg herself. Therefore, the system of checks and balances can only operate in the bounds of the information available to the court at the time, and the validity of evidence as supported by experts.

Conclusion

The Folbigg case teaches us valuable lessons about justice in Australia. Firstly, we see equality, with a society that values justice for all even those who are babies and children. We also see checks and balances for those who have been convicted of crimes able to have their convictions reviewed when new evidence arises, even after court processes have been exhausted and much time has elapsed.

We see the importance of protecting the presumption of innocence, how crucial it is that the prosecution is burdened with proving beyond reasonable doubt that the offence has been committed, and that this not be impacted by cases of an extreme or unusual nature. Finally, we see both the positive and negative role of the media and non-legal measures in providing justice for victims, offenders and society.