Part II: Human Rights Breaches- Arbitrary Interference on Right to Privacy

How does NSW ICAC measure up?

NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption (“ICAC”) first principal function as set out in the Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988 (“ICAC Act”) is to investigate and expose corrupt conduct in the public sector. This function serves to enhance transparency and trust within the community by exposing corruption, ensuring that any public officials who act in breach of their duties are made accountable to the public.

ICAC however, has been designed to expose corruption but its design has a significant flaw.

NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption (“ICAC”) first principal function as set out in the Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1988 (“ICAC Act”) is to investigate and expose corrupt conduct in the public sector. This function serves to enhance transparency and trust within the community by exposing corruption, ensuring that any public officials who act in breach of their duties are made accountable to the public.

ICAC however, has been designed to expose corruption but its design has a significant flaw.

It does not permit anyone to test the merits of its findings and has become an entity that is presumed to be infallible.

Without an exoneration process, those found guilty of corruption have no avenue to have their innocence restored or to mount a compelling case to show that they are innocent of a crime.

It is important to note that when ICAC declares someone ‘corrupt’ they do not necessarily mean ‘guilty of a criminal offence’ or ‘in breach of the law’ – that is the power of the Courts. It is central to the rule of law that people may only be punished under the law. Without the judicial power possessed by the Courts, ICAC is prohibited from exercising such powers of punishment. With this in mind, how could it be fair that when ICAC makes a finding of corruption, a person’s reputation is forever tarnished? Not only are there photos of the person and their family in the newspapers, their bank accounts may be frozen, they are restricted in where they can travel and places they can visit. For those with no criminal proceeding taken, there is no adequate procedural safeguards built into the design of ICAC to challenge the findings of ICAC and they are left with the permanent scar of a corrupt findings with no avenue of redress.

As argued in our Submission in 2020, an exoneration protocol should be available to those who have been acquitted by a court or who have never been charged over matters that have been investigated by ICAC. It should be available only to those who are entitled to a presumption of innocence. (It would not be available to those found guilty by a court of an offence based on the same or similar facts that formed the basis for an adverse finding by ICAC.)

To illustrate, consider the case of Mr Charif Kazal.

Case Study – Charif Kazal

Mr Charif Kazal was found guilty of corruption by ICAC in 2011. The advice of the DPP was obtained with respect to the prosecution of Mr Kazal but the DPP advised that there was insufficient evidence to proceed. As a result, Mr Kazal was never charged over the matters that were investigated by ICAC.

With no criminal proceedings, Mr Kazal was left with the stain of a corrupt finding by ICAC, with no way to test the merits of ICAC’s determination.

Click here to see all the avenues Mr Kazal took for domestic remedies of justice.

With no avenues within the design of ICAC to challenge the findings, Mr Kazal made a complaint to the United Nations Human Rights Committee.

In late November 2023, the UNHRC released its findings and concluded that;

“the inquiry conducted by ICAC, and its adverse public findings made against [Kazal] which he could not challenge, amounted to a violation of [Mr Kazal’s] rights under article 17 of the [International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights].”

Article 17 reads:

1. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation.

2. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

Mr Kazal’s experience highlights how the lack of review mechanisms stopped him from testing the findings of ICAC and contravenes not only Australia’s obligations to uphold international human rights, but also the notions of ‘procedural fairness’ and ‘the presumption of innocence’, values that are highly regarded in every other facet of Australian law.

This case also raises the question; how many more individuals are in Mr Kazal’s position who have been publically named as corrupt by ICAC but have been unable to clear their name through any means of review?

Review of ICAC Annual Report 2023:

Human Rights Breaches by ICAC: Number of Australians who have no way to test the findings of ICAC?

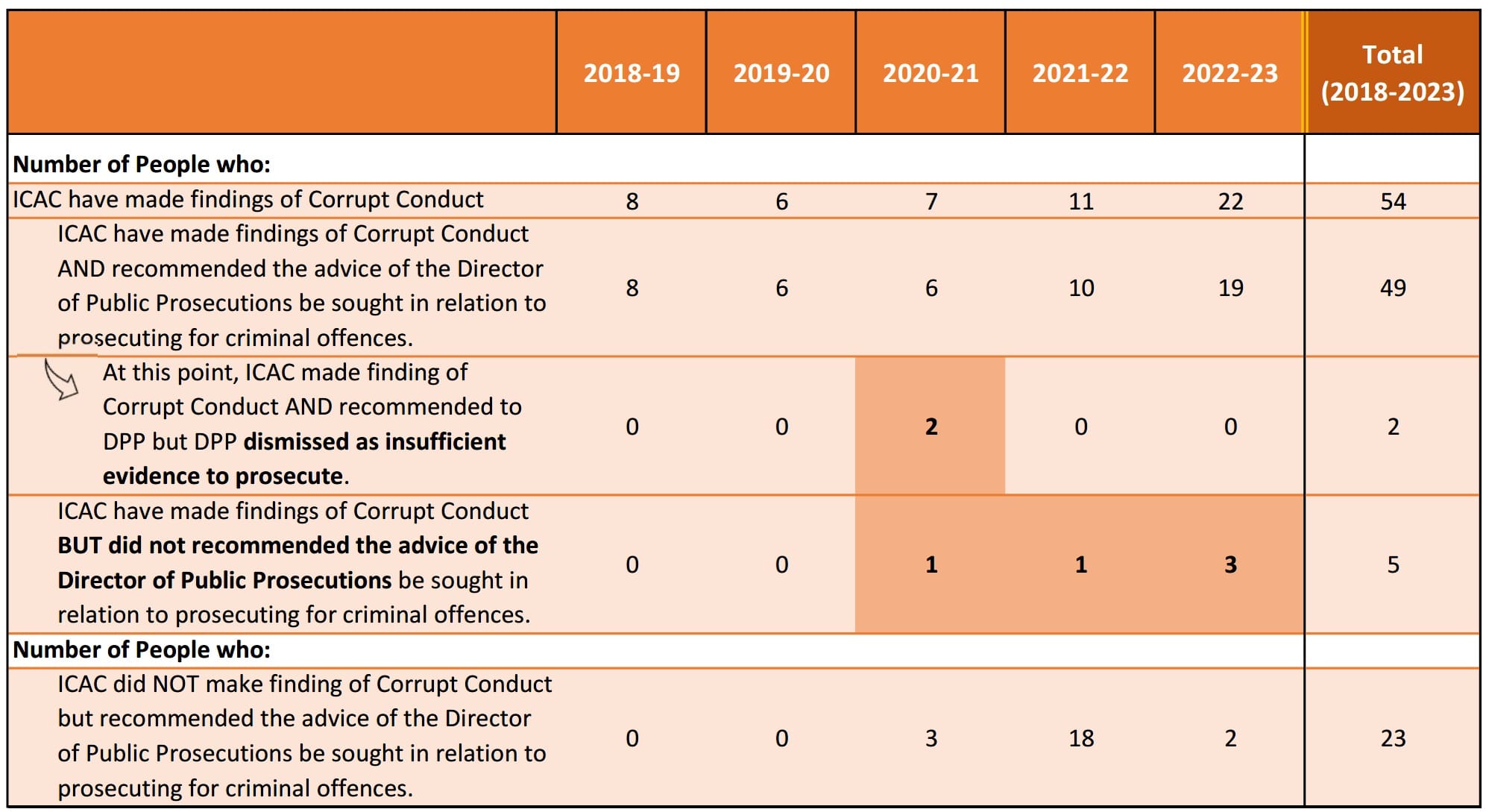

Our research aimed to answer the question of the ICAC’s reach and how many people have had their reputation tarnished and their rights violated with no way to test the findings of ICAC.

We asked, how many people have ICAC declared ‘corrupt’ without sufficient evidence to proceed with a criminal charge?

Our findings are as follows:

From our research, we have identified 7 people (highlighted) who are innocent under the law but have had a ‘corrupt’ finding made by ICAC.

In the last 3 years, this group comprises 17.5% of all peoples against whom the ICAC has made findings of corrupt conduct. This issue was particularly severe in the period 2020-2021, in which almost half of all individuals declared ‘corrupt’ were, in fact, legally innocent! Yet, the reputational ‘stain’ of the ICAC’s publications continues to hang over them.

We note also this report contains 72 people in the last 5 years who ICAC has sought the advice of the DPP in relation to prosecution. Of these 72 people, 58 still either have their ‘Brief of Evidence in Preparation’ or ‘Brief of Evidence Submitted.’ This means, the DPP might still decide that there is insufficient evidence to commence proceedings for a criminal offence.

Among the highlighted individuals, one of the statistics in 2022-2023 is former NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian, who was declared to have engaged in serious corrupt conduct, but not guilty of any criminal offences. As a politician, the ICAC’s declaration had devastated her reputation and career – contrary to the rule of law, with no way adequate protocols to test those findngs or avenue of redress.

Brief Comment on Methodology

In this report, we examined data from ICAC’s Annual Reports and website publications over the past 5 years. Publicly available on the ICAC’s website is their history of past investigations, detailing the names of individuals who had been under investigation for corruption, as well as which of those individuals had been declared corrupt and which had been recommended to the Director of Public Prosecutions for allegations of criminal conduct.

The ICAC’s most recent 2022-2023 Annual Report also provides information on the current status of each investigation, including whether or not it was pursued by the DPP.

General enquiries about the rule of law and the work of the Institute: info@ruleoflaw.org.au

Inquiries regarding school visits, education programmes and resource requests: education@ruleoflaw.org.au

Inquiries regarding our Court Visit programmes: courtvisit@ruleoflaw.org.au